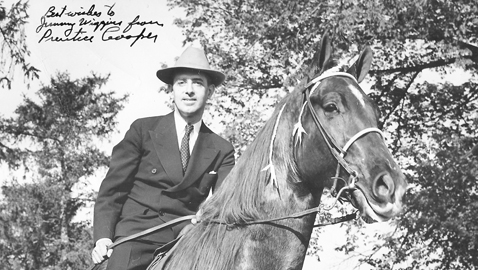

By Ray Hill

Prentice Cooper was barred by state law from seeking yet another term as Tennessee’s governor in 1944; there was no Senate seat to contest and he was faced with the prospect of retiring from public office. Cooper clearly wanted to remain in public life and at age 48, he was unmarried and had no children. After having served as governor for six years, the prospect of returning to a small town law practice held little appeal for him.

At the 1944 Democratic National Convention, Prentice Cooper was Tennessee’s favorite son for the vice presidential nomination. There was a real fight for the vice presidential nomination that year as an ailing Franklin Delano Roosevelt apparently quietly encouraged the campaigns of several potential vice presidents, including that of incumbent Vice President Henry A. Wallace.

Wallace had been FDR’s choice to run with him in 1940 when Vice President John Nance Garner, a violent opponent of a third term for any man, had actually opposed Roosevelt for renomination. Garner had gone home to Ulvalde, Texas while many Democrats rebelled at the notion of nominating Henry Wallace for the vice presidency.

Henry Wallace was a peculiar choice for the Democratic vice presidential nomination as he had been, of all things, a Republican for most of his life. He had never been elected so much as constable and possessed little or no political acumen. Wallace brought very little to the ticket in the way of political strength and Speaker of the House William Bankhead desperately wanted the honor of serving as vice president. FDR was shocked and angry when delegates grew so mutinous there was a very real possibility they would refuse to nominate Wallace. Roosevelt issued a statement if Wallace were rejected by the convention, he would refuse the presidential nomination. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt hurried to Chicago to help nominate Henry Wallace.

The delegates grudgingly nominated Wallace, but the candidate was so roundly booed by delegates that Mrs. Wallace burst into tears.

By 1944, FDR had accepted the fact that Wallace was a liability in his bid for a fourth term. Roosevelt had a fundamental dislike of confrontation as well as a pronounced devious streak. He encouraged Wallace to seek renomination as vice president, while encouraging others to run as well. There were several Democrats running for vice president that year who believed they had FDR’s blessing.

Roosevelt himself gave Henry Wallace a statement saying were he a delegate, the president would vote for Wallace. President Roosevelt also gave Robert Hannegan, the Chairman of the National Democratic Party, a letter stating he would be happy to run with either Missouri Senator Harry Truman or Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

Hannegan was himself from Missouri and quietly promoting the candidacy of Harry Truman, who emerged from the convention as the Democratic nominee for vice president.

Prentice Cooper returned home to the governor’s mansion having had the honor of being Tennessee’s favorite son for the vice presidency. As Cooper’s term as governor drew to a close, Tennessee’s powerful senior U. S. Senator Kenneth McKellar took up Cooper’s cause. The two were personal friends and McKellar’s original support had helped Prentice Cooper win election as governor in 1938.

Senator McKellar importuned President Roosevelt to appoint Prentice Cooper to a post in the Roosevelt administration. McKellar sent several letters proposing Cooper for a variety of appointments. An ill, war-weary and distracted Roosevelt did little more than acknowledge McKellar’s letters and the president died within months of his reelection to an unprecedented fourth term.

Senator McKellar had carefully outlined the successes of the Cooper administration in Tennessee and there were many to cite.

When Prentice Cooper took the oath of office a governor of Tennessee, the state debt was more than $126,000,000, a huge sum at the time. By the time Prentice Cooper had completed his first term of office, he had trimmed the state budget by some $21,000,000; by comparison all the governors of Tennessee previously had reduced the state debt by approximately $6,000,000. Cooper slashed the state payroll by several hundred thousand dollars and the only tax increased during his administration was on alcohol.

Despite being an economy-minded governor, Prentice Cooper managed to actually increase state aid to the elderly and infirm. Cooper increased the number of free textbooks to children in elementary schools and increased funding for public health.

With the advent of World War II, Prentice Cooper’s responsibilities as governor increased dramatically. Working closely with Senators K. D. McKellar and Tom Stewart, Cooper helped to attract wartime industries to Tennessee. Fifteen armories were built across the state, including one such facility in the governor’s hometown of Shelbyville. With Senator McKellar presiding over the Senate’s Appropriations Committee, more than a billion dollars (the equivalent of some $65 billion in today’s dollars) flowed into Tennessee.

Governor Cooper quickly mobilized a State Defense Council even before President Franklin Roosevelt had proclaimed a state of national emergency. Cooper had to oversee the draft registration of some 900,000 Tennesseans and appoint representatives to no less than 132 draft boards across the state.

Harry Truman, the little man from Missouri, succeeded FDR and was soon the recipient of McKellar’s letters urging an appropriate appointment for Prentice Cooper. Truman, a former senator himself, knew the clout McKellar carried in the United States Senate and nominated Cooper to serve as Ambassador to Peru.

It was hardly a top diplomatic post, but McKellar was happy to have secured a position for the former governor. The Senate confirmed Cooper’s appointment and the former governor boarded a ship to make the journey to the American Embassy in Lima, Peru. The bachelor Cooper departed with his mother, who would once again serve as his official hostess as she had during her son’s gubernatorial administrations.

Prentice Cooper’s personality was perhaps not suited to the role of a diplomat and it is hardly surprising that the peppery former governor soon won a reputation for being plain spoken to the point of being blunt. With World War II ended, Cooper’s post as Ambassador to Peru was not taxing and there was virtually no controversy with his tenure as America’s representative in Peru.

The former governor’s mother suffered a serious heart attack while living at the Ambassador’s residence and Cooper was naturally worried about her. The best physicians in Peru tended to her, but Cooper quickly brought her back to the United States for treatment. Mrs. Cooper made a full recovery, which greatly relieved her only child.

Prentice Cooper resigned his post as Ambassador to Peru in 1948 and returned to Tennessee. Cooper managed the considerable family holdings and practiced law in Shelbyville. He began courting a lovely young woman named Hortense Powell, who was considerably younger than the former governor. The two were married in 1950 and produced three sons in short order.

The lure of politics was never far from Prentice Cooper in his retirement and he was mentioned as a prospective candidate in 1952 for the United States Senate should incumbent Kenneth McKellar not run. Cooper was again widely discussed as a possible challenger to Senator Estes Kefauver and Governor Frank Clement in 1954.

It was 1958 when the sixty-three year old Prentice Cooper decided the time was right for a political comeback. For the first time since 1944, there would be no incumbent running for governor of Tennessee and telegrams arrived in the editorial offices of newspapers on New Year’s Day 1958 announcing Prentice Cooper was again running for governor.

Frank Clement had served six years as governor and was ineligible to run for reelection, but a myriad of candidates were eager to succeed him. Edmund Orgill, Mayor of Memphis, Judge Andrew “Tip” Taylor, and Buford Ellington were all serious candidates for the Democratic nomination for governor. None possessed the stature of Prentice Cooper nor did any have the statewide contacts of the former governor.

For several months, Prentice Cooper stumped Tennessee and appeared frequently on television, which was now an important media outlet. Yet after having campaigned for the gubernatorial nomination for half a year, in June of 1958 Prentice Cooper abruptly withdrew from the gubernatorial race and announced he would instead oppose Senator Albert Gore for renomination.

It was a curious decision. Considering the number of candidates vying for the Democratic nomination for governor, Prentice Cooper would have seemed to be a very strong contender with an excellent prospect of victory, especially in a crowded field. There were a vocal number of influential citizens in Tennessee who were deeply unhappy with Albert Gore who along with Tennessee’s other senator, Estes Kefauver, had refused to sign the Southern Manifesto, proclaiming white supremacy.

Kefauver had survived a bitter reelection campaign in 1954, facing Congressman Pat Sutton who had access to ample funds and lost badly. Segregationists proposed to defeat Gore in the 1958 and Prentice Cooper became the candidate of segregation.

Like Sutton, Prentice Cooper’s campaign for the United States Senate did not seem to lack for funds. Campaigning on a slogan as “Your U. S. Senator”, Cooper proclaimed he would be a senator for “the Southern way of life.”

Gore, on the defensive, explained he had, like many other Southern senators, helped to water down the Civil Rights legislation in Congress to the point where it meant little, save for giving African-Americans the right to vote. Senator Gore declared he was for allowing anyone to have the right to vote.

Cooper’s campaign for the Senate, launched only in the last two months before the primary election, fell far short. Once again Cooper lost his home county of Bedford and lost three of the four urban counties. With E. H. Crump dead, Cooper lost Shelby County by almost 18,000 votes; he lost Davidson County by an even greater margin. Cooper did carry Hamilton County by almost 7,000 votes and ran well in some West Tennessee counties, but he amassed only 253,000 votes to 375,000 for Gore.

It is interesting to note just how close the gubernatorial primary was that year; Buford Ellington eked out a win with 213,000 votes, closely followed by Andrew “Tip” Taylor with 204,629 and Edmund Orgill with 204,382. Prentice Cooper lost the Senate race while garnering 40,000 more votes than Buford Ellington who won the Democratic nomination for governor. One wonders if Cooper might not have again known victory had he remained in the governor’s race.

Prentice Cooper resumed his business interests and law practice in Shelbyville and he and Mrs. Cooper kept up an interest in all things historical. They enjoyed a happy and contented life, residing in the Victorian mansion that had been the Cooper home for decades.

In the late 1960s Prentice Cooper was suffering from stomach cancer. The former governor went to the Mayo Clinic in hope of making a recovery, but Prentice Cooper died there on May 18, 1969.

Prentice Cooper always maintained the goal of his administration as governor of Tennessee was to deliver “honest and efficient” government to the people. Despite never having been a business executive, Prentice Cooper managed state government in a thoroughly efficient and business-like manner. He kept his word to the people of Tennessee.