Election fraud is nothing new to politics, nor to Tennessee politics, for that matter. In some states, it was a staple of the election cycle.

Charges of election fraud in Tennessee elections have been almost common place throughout history. William G. “Parson” Brownlow had troops stationed at polling places during one of his gubernatorial bids. Yet one of the little remembered cases of election fraud was the gubernatorial election of 1894 where incumbent Governor Peter Turney faced off against popular Republican H. Clay Evans.

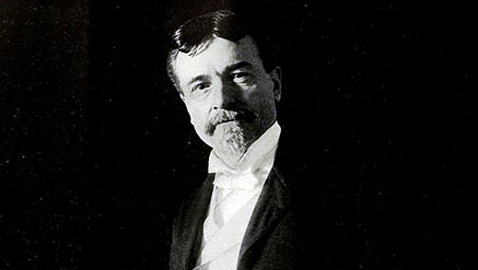

Turney was born September 22, 1827 in Jasper, Tennessee. Peter’s father was Hopkins Lacy Turner, who was a Congressman and United States senator from Tennessee. The younger Turney had many more advantages than his father; the elder Turney supposedly never attended school and could not even sign his name until he was twenty-two years old. Hopkins Turney was the very definition of a self-made man.

Considering his father’s success in politics, it is hardly surprising Peter Turney followed Hopkins Turney in both the practice of law and politics. Young Peter Turney commenced the practice of law in Winchester, Tennessee, where his family had moved when he was a small child. Turney campaigned for John Breckenridge of Kentucky in the hotly disputed election of 1860. That year saw Republican Abraham Lincoln challenged by Democrat Stephen Douglas of Illinois, Breckinridge, who had been Vice President of the United States under President James Buchanan, and Tennessean John Bell, who ran as the candidate of the Union Party. Breckinridge was the candidate of Southern Democrats and Peter Turney strongly sympathized with his fellow Southern Democrats. Turney was strongly for secession from the Union and even supported the idea of Franklin County seceding and joining the State of Alabama. Turney hurried to raise a regiment of troops and did so before Tennessee had officially seceded from the United States. Turney took his troops to Virginia where they fought in the first battle of Bull Run. Turney and his soldiers were fighting at Fredericksburg when he was seriously wounded, having been shot in the mouth. His recovery was slow and Turney spent the remainder of the war, serving in an administrative capacity in Florida, well away from the front lines.

Peter Turney’s first forays into politics were less than successful. He was a candidate for Attorney General for his local circuit, but lost. He was nominated for the United States Senate in 1876 and lost yet again.

With Tennessee having rejoined the Union, Peter Turney was elected to the Tennessee State Supreme Court. Turney won reelection twice, in 1878 and 1886 and eventually served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Peter Turney’s rise to the governorship came with Governor John P. Buchanan having been weakened due to the controversy of the “Coal Creek War”. The Cold Creek War was a labor uprising, which occurred in Anderson County. Mine owners thought to replace mine workers with convicts, which they proposed to lease from the State of Tennessee. Infuriated miners retaliated against mine owners by burning property, including the stockades where prisoners were housed. The conflict quickly escalated into armed warfare.

John Price Buchanan had been something of a political wunderkind. A former member of the Tennessee General Assembly, Buchanan had become President of the Tennessee’s Farmer’s Alliance. Later, the organization would join together with the Laborer’s Union and Buchanan would serve as president of the combined groups. Buchanan won the loyalty and affection of many Tennessee farmers when he sponsored legislation to exempt the cooperative stores of the Farmer’s Alliance from a tax imposed upon merchants.

Buchanan won the 1890 Democratic nomination for governor, strongly supported by farmers and their allies. Buchanan’s nomination surprised Tennessee’s more conservative Bourbon Democrats and while he won the general election easily, they never really liked nor supported Buchanan.

Governor Buchanan was considered friendly to the miners, yet his handling of the Coal Creek War won him criticism from both sides. Peter Turney was supported in his gubernatorial campaign by more conservative Democrats, as well as businessmen and those who strongly supported big business. It quickly became apparent John Buchanan could not win renomination as governor and he dropped his bid for the Democratic nomination and declared he would seek reelection as an Independent. Turney easily won the general election and Governor Buchanan won only 31,515 votes in the general election.

Governor Buchanan’s defeat ended his political career and while he would live almost another forty years, he was never again a candidate for political office. He returned to his home in Murfreesboro, where he died in 1930.

Governor Turney’s first term proved to be tumultuous. Although he had issued rulings seemingly favorable to the convict leasing system while on the Tennessee Supreme Court, he signed legislation ending the practice of competing with labor. There was also a serious downturn in the economy in 1893, which affected Turney’s administration as well as his personal popularity. Governor Turney was politically vulnerable when he sought reelection in 1894.

Tennessee Republicans nominated H. Clay Evans, a former Congressman from Chattanooga, who had been blatantly gerrymandered out of his Congressional seat. Evans was a striking-looking man and an able speaker. Evans had a full head of hair and wore a moustache and wisp of a beard under his lower lip. He looked rather like what one might think a successful Southern planter might look like. Governor Turney did not have the same imposing physical presence as his opponent. A balding, somewhat corpulent man with a wispy beard, he was not at all impressive in appearance.

Evans had been quite successful in business, served as Mayor of Chattanooga twice, the State Senate, as well as a term in Congress.

Peter Turney was not at all H. Clay Evans’ equal on the stump and it was soon clear the Democrats had a real fight on their hands.

Governor Turney tried hard to stem the tide and assailed Evans again for his support of the “Lodge Bill”, which guaranteed the voting rights of black citizens. Turney also scored Evans as a carpetbagger, as Evans had been born in Pennsylvania and married his wife in New York.

As the election returns came in, it was apparent Evans had won. The initial tally was 105,104 votes for H. Clay Evans and 104,356 votes for Peter Turney. A third candidate, A. J. Mims, a Populist, had won 23,088 votes.

The delight of Tennessee Republicans soon turned to dismay, then outrage. The Tennessee General Assembly, whose majority was composed of Democrats, reversed the popular election results. Legislators insisted that the election had been rife with voter fraud and negated some 23,000 ballots, which gave Governor Turney a scant plurality.

Republicans were furious, but there was little they could do.

Governor Turney’s second administration was even less successful than his first; Turney was tainted by the stolen election and seemed virtually paralyzed in office. Turney could not even manage to adequately plan for Tennessee’s centennial celebration, leaving it to his successor. To add to hos woes, the governor’s brother, Joseph Turney, was accused of operating a chain gang for his own profit.

While he had officially won the election of 1894, it was a pyrrhic victory. It kept the Democrats in power in Nashville and while they controlled the governor’s office, Peter Turney was finished in Tennessee politics.

After leaving office, Peter Turney returned to Winchester where he died in 1903. Turney was married twice and fathered thirteen children.

H. Clay Evans enjoyed a successful political career. He had been Mayor of Chattanooga and helped to organize the first public school system in Hamilton County. Although he lost his seat in Congress, largely due to his support for legislation to safeguard the voting rights of African-Americans, he became Postmaster General under President Benjamin Harrison. Evans was in charge of GOP patronage and used it effectively. While his loss of the 1894 gubernatorial race was a bitter disappointment, Evans was hailed by fellow Republicans nationally. He was a candidate for the GOP vice presidential nomination in 1896 and ran second to the eventual nominee, Garrett Hobart. The Republicans succeeded in electing William McKinley president that year and McKinley appointed H. Clay Evans as Commissioner of Pensions in his first administration. Following McKinley’s assassination, President Theodore Roosevelt named Evans to the prestigious post as United States Consul to Great Britain in 1902.

After returning from Europe, Evans again settled in Chattanooga and ran for office once again successfully, becoming Commissioner of Health and Education under the new Commission form of government.

Evans remained a leader of Tennessee Republicans, but there was fierce infighting amongst members of the GOP for control of the federal patronage under Republican presidents. Evans served as a Trustee for both the University of Chattanooga and the University of Tennessee in the later years of his life.

The contrast in the lives of Peter Turney and H. Clay Evans following the election of 1894 is almost impossible to overlook. Turney left office disgraced and discredited, while Evans went on to greater honors and remained a highly respected and admired leader of his party. Even the former governor’s fellow Democrats shied away from Peter Turney and he retired to relative obscurity.

H. Clay Evans died in his sleep on December 12, 1921 and was far more celebrated and respected than his former rival Peter Turney despite never having served as governor of Tennessee.