Just after the turn of the century, Tennessee’s Democratic Party became almost hopelessly fractured. The candidacies of two men helped to heal the deep divisions inside the Democratic Party in Tennessee: that of Kenneth D. McKellar for the United States Senate in 1916 and Tom C. Rye for governor in 1914.

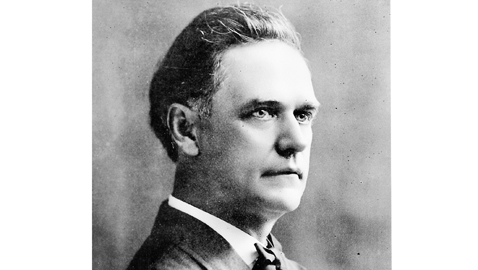

Thomas Clarke Rye was born June 2, 1863 in Benton County; Rye was the son of a reasonably successful storekeeper and farmer. Young Tom expressed an interest in the law and as was common at the time, “read” the law under the supervision of his uncle, Thomas Morris. Once he had been admitted to the Bar, Tom C. Rye moved to Camden, Tennessee where he commenced the practice of law. It was not long after he had been admitted to the Bar that Tom took a bride, marrying Betty Arnold in 1888.

Rye served as the Clerk and Master for the Chancery Court in Benton County and later lived in Washington, D. C. where he worked as a pension agent. When Tom C. Rye moved back to Tennessee, he relocated to Paris in Henry County and got himself elected district attorney. Rye earned notoriety as strictly enforcing the law, as well as cracking down on bootleggers. The future governor was an ardent prohibitionist and he had no sympathy whatever for those making illegal whisky or moonshine.

The gubernatorial administration of Governor Malcolm Rice Patterson had shattered Tennessee’s Democratic Party. Challenged by former Senator Edward Ward Carmack in 1908, Patterson had narrowly been renominated. The ill feelings between Governor Patterson and Senator Carmack went back to 1894 when Carmack had defeated Patterson’s father, Josiah, for reelection to Congress. Carmack was himself a strong supporter of prohibition, while Governor Patterson was both personally and politically “wet”.

After his defeat for the gubernatorial nomination in 1908, Carmack returned to his former vocation as a newspaper editor, having been hired by Luke Lea to be the editor of the Nashville Tennessean. Carmack, still seething over his loss, tormented the governor and Patterson’s allies in print without mercy. Caramck, encountering Colonel Duncan B. Cooper and his son Robin on a Nashville street, was left dead in the gutter after shots were exchanged.

Governor Patterson pardoned Colonel Cooper and was seeking a third two-year term when the Democratic Party in Tennessee came apart at the seams. Most of the state Supreme Court bolted the Democratic Party, announcing they would seek reelection as “Independent” Democrats and promptly formed an alliance with the Republicans. Patterson was stunned when the “Fusionist” ticket soundly thrashed his own slate of regular Democrats. Patterson quickly concluded he could not be reelected and withdrew as a candidate. Democrats urged Senator Robert Love Taylor, perhaps the most personally popular Democrat in the state and a former three-term governor, to run against Fusionist candidate and Republican nominee Ben W. Hooper. The divisions inside Tennessee’s Democratic Party were so deep, even Taylor could not beat Hooper in 1910.

Luke Lea immediately took advantage of those divisions and was elected to the United States Senate in 1911 with the support of Independent Democrats and Republicans. Tennessee had just elected its first Fusionist U. S. senator.

When Governor Ben W. Hooper sought reelection in 1912, Democrats were still not united. Benton McMillin, a former governor, was the Democratic nominee to challenge the Republican chief executive, but he had no better luck than Bob Taylor and lost. Just after Hooper’s reelection, the Tennessee General Assembly convened and Democrats struggled to maintain control of Tennessee’s other U. S. Senate seat. Incumbent James B. Frazier very much wanted to be reelected, but it soon became clear he did not have the votes to win. Once again, a combination of Independent Democrats and Republicans elected a senator, choosing State Supreme Court Justice John Knight Shields. By 1913, the Fusionists had elected the governor and both United States senators.

It was the high tide of the Fusionist movement in Tennessee.

Hooper wanted a third two-year term as governor in 1914, but Democrats had finally coalesced around the candidacy of district attorney Tom C. Rye. Fifty-one years old in 1914, Rye waged an effective campaign and Democrats of every stripe endorsed his candidacy. Rye defeated Governor Hooper, winning 137,656 votes to the incumbent’s 116,667 votes.

E. H. Crump, emerging as the leader of the Shelby County political organization, earned some unwanted statewide attention when Governor Hooper complained he had been defeated by the large vote won by Tom C. Rye in Crump’s domain. Hooper believed the vote in Shelby County was fraudulent.

If grateful to Crump for his support, Governor Rye had an odd way of showing it. Crump was anything but a prohibitionist and the governor supported an “Ouster” law, which permitted the removal of any officeholder who refused to enforce the prohibition law. The bill was aimed squarely at Memphis Mayor E. H. Crump, who was notorious for his refusal to strictly enforce prohibition in the Bluff City. Crump resigned before being removed and several other Memphis officials were ousted from office, along with others in Nashville and Knoxville.

Governor Rye was responsible for the creation of Tennessee’s State Highway Department, the forerunner of the Department of Transportation. Tennesseans were soon having to register their automobiles and the governor implemented a highway tax to help pay for roads. Rye also supported a tax for the benefit of Tennessee’s schools and was one of the few governors who did not suffer for it at the polls for increasing taxes.

Tom C. Rye sought a second term in 1916, which was also the first year Tennesseans popularly elected their first United States senator. Luke Lea was a candidate to succeed himself, but drew strong opposition from former governor Malcolm Patterson and Memphis Congressman K. D. McKellar. Rye did his best to avoid entangling himself in the complicated Senate race, as both Senator Lea and Governor Patterson had strongly supported him in 1914. Lea and Patterson were polarizing figures in Tennessee politics and McKellar ran more as a “harmony” candidate, one who could appeal to every faction inside the Democratic Party. Neither Lea nor Patterson paid much attention to McKellar’s candidacy and just about everybody was shocked when McKellar won the first round of balloting, carrying East and West Tennessee. Lea was eliminated in the first primary and McKellar repeated the feat in the run-off election, carrying East and West Tennessee to defeat Patterson and earn the right to face former Republican governor Ben W. Hooper in the 1916 general election. Senator Lea had expected an open endorsement from Governor Rye and was deeply disappointed when he did not get it.

Governor Rye and Congressman McKellar stumped the state and posters urging the election of the Democratic ticket appeared all over Tennessee. President Woodrow Wilson, Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, Governor Rye, Congressman McKellar, and Colonel B. A. Enloe comprised the Democratic ticket in Tennessee and the Democrats handily won the election. Governor Rye defeated his Republican opponent, John W. Overall, with 146,758 votes to 117,817. McKellar, facing the more popular Ben W. Hooper, won 143,718 votes to the former governor’s total of 118,174 votes.

President Wilson despite having campaigned on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War”, soon led the United States into World War I. More than 80,000 Tennesseans took part in the war and only the number of Tennesseans fighting in the Civil War exceeded that of those in Europe fighting in the World War.

Governor Rye signed into law Tennessee’s first real primary election law and henceforth candidates would be selected by voters inside party primaries.

Tom C. Rye could have sought a third two-year term in 1918, but instead he opted to challenge the last remaining Fusionist in office, Senator John Knight Shields.

Rye was still popular and had every expectation of defeating the crusty Senator Shields. Rye was from West Tennessee, while Shields was a native of Republican dominated East Tennessee. Senator Shields had quietly backed the senatorial candidacy of Kenneth McKellar in 1916 and his junior colleague proposed to return the favor in 1918. McKellar learned that President Wilson, who disliked John Knight Shields, intended to send a letter for public consumption to Tennessee stating the senator was no friend to Wilson. Senator McKellar realized if the president sent any such letter, Shields would lose the primary election to Governor Rye.

McKellar managed to convince the president not to send the letter and had little difficulty in convincing his friend E. H. Crump to back Shields’s reelection bid. Shields very narrowly won renomination and was easily reelected in the general election.

Tom C. Rye accepted the verdict of Tennessee Democrats and returned to Paris and began practicing law once again. Rye was offered the post of Chancellor for the Eighth Judicial District in West Tennessee and accepted. The former governor remained on the bench until 1940 when he decided to retire. Rye summoned another former governor from West Tennessee to his office, Gordon Browning. Rye told Browning he was ready to retire if Browning would run for Chancellor to succeed him. Out of office and humiliated in the 1938 election, Browning agreed to run and Tom C. Rye ended his career in Tennessee politics.

Governor Rye lived another thirteen years, remaining in Paris, Tennessee until his death on September 12, 1953 at age ninety.