From Big Band Leader to Politician

Victor A. Meyers

Victor Aloysius Meyers lived to be 93 years old, a fact which astonished some of those who knew him. Tacoma, Washington, attorney John J. O’Connell said, “You’d think a man who had that much fun tasting the good things in life would die at a younger age. He was one of the delightful people in politics.” There was a time when tens of thousands of people in Washington State could remember being greeted by Vic Meyers’ tradition booming, “Hiya, kiddo!” In 1932, Meyers showed up in Olympia intending to file to run for governor. When the clerk in the secretary of state’s office told Meyers the filing fee was $60, he replied, “What have you got for $20?” The filing fee for lieutenant governor was $12 and Meyers paid it and won the election. “I never wear a vest, because I don’t want to be accused of standing for vested interests,” Meyers once quipped.

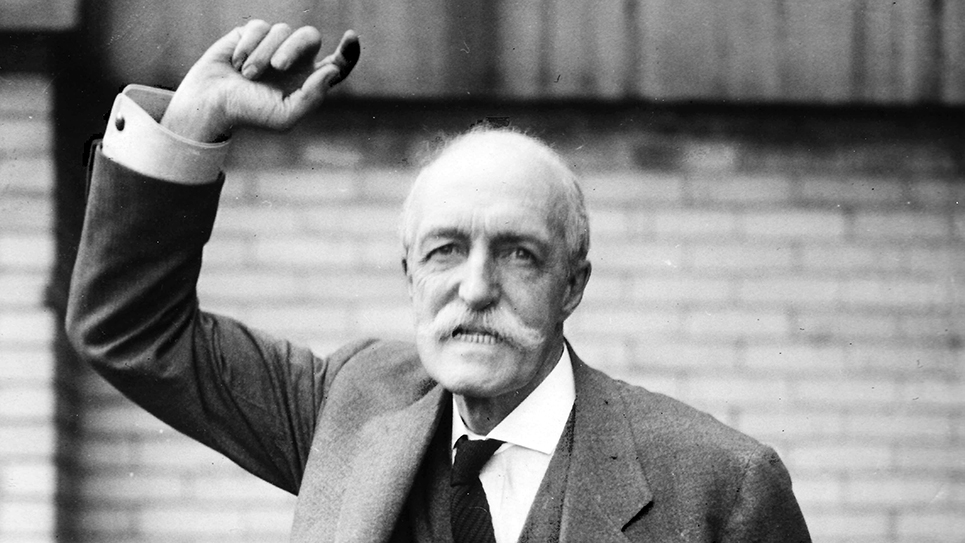

A dapper man who sported a debonaire moustache like that of swashbuckling movie star Errol Flynn, he reputedly enjoyed the good life as did Flynn. There, the resemblance ended between the two. Meyers drove a Cadillac, smoked expensive cigars, played the horses, wore nice clothes, and was an “extravagant extrovert.” For three decades, Vic Meyers was an institution in Washington state politics. Vic Meyers always enjoyed a good joke, even if it was on himself. When one political opponent, tired of Meyers’s grandstanding, hired every sound truck in the city to roar through neighborhoods at 3 a.m., blaring the message, “Wake up and vote for Vic Meyers!” the candidate mused, “I wish I’d thought of that.” When another opponent hurled the accusation at him that he was a Communist, Meyers replied, “Then I’m the only Communist named Aloysius.”

When Vic Meyers died at the ripe old age of 93, Secretary of State Ralph Munro told a reporter, “It really is the end of an era. For all the jokes about him, everyone remembers him. How many Washingtonians can remember any governor of that era?”

There is an ever-growing list of those who move from the entertainment industry into politics; perhaps there is an even greater number of individuals who leave politics for the entertainment industry. Those ex-officeholders who populate every news channel on cable television can be considered as having entered the entertainment industry, as it could hardly be considered the realm of real journalism any longer.

One of sixteen children, nobody had to tell Vic Meyers he had to make his own way in life. At various times, Meyers farmed, raising corn, ran a motel, managed a golf course, and laughed about having bought a chicken ranch only to see his entire flock of 3,500 chickens die.

Having run a campaign for mayor of Seattle as a joke in early 1932, Meyers campaigned with an eye toward publicity and showed up at one event dressed like Mahatma Gandhi, wearing a white sheet and pulling a goat on a rope while playing the flute. That event was a businessman’s luncheon, and Meyers decades later recalled, “Times were tough. They stood for the rich, I was the poor man’s candidate.”

Discovering he actually enjoyed politics, Meyers entered the race for lieutenant governor. Much of one’s success in politics can be attributed to timing, and that was certainly true for Vic Meyers. Running as a Democrat in 1932, the year of Franklin D. Roosevelt, was particularly good fortune. The Democrats swept everything before them in the Evergreen State that year. It was the first of Meyers’ five terms as Washington’s lieutenant governor. There were those who thought Meyers’ background as a big bandleader, having performed in bars and speakeasies, made him especially well suited to presiding over the state Senate in Olympia. A true American original, a goodly number of people enjoyed Meyers’ showmanship and antics, but the downside was that few took anything he said seriously. Vic Meyers proposed several projects that became highly successful and much appreciated, but at least initially, they were laughed at and scorned because they had been proposed by the fun-loving Meyers. When the Lieutenant Governor suggested building a park and golf course in Eastern Washington, the chortling could be heard all over the state, with some labeling the project as “Vic’s folly.” The end result was Sun Lakes Park near the massive Grand Coulee Dam. To this day, it remains one of the busiest parks in the state of Washington. The Washington State Legislature renamed the golf course a few years ago for Vic Meyers. So, too, did people laugh when Meyers suggested Seattle for the site of the World’s Fair originally. Meyers would run twice more to become mayor of Seattle, losing to Republican Arthur Langlie in 1938 and incumbent William Devlin in 1946.

When Meyers had run his gag campaign for mayor of Seattle, he was one of the best-known figures in the city, as he owned his own nightclub where he and his band played. Meyers was frequently in hot water with local officials who enforced the prohibition laws. Meyers was nudged into the race by Doug Welch, the city editor of the Seattle Times, who gave the candidate huge publicity. Vic Meyers campaigned from behind the wheel of a beer wagon in a flagrant display of his contempt for the prohibition law, much to the amusement of thousands of residents.

While campaigning in 1932, Meyers adopted a more serious tone and discussed real issues like child labor laws, the need for pensions (there was no Social Security at the time) and some form of unemployment compensation, as there were millions of Americans out of work and unable to find work in the midst of the Great Depression. Meyers won the Democratic nomination and served alongside Governor Clarence D. Martin. Vic Meyers and his big band played at the inaugural ball of Governor Clarence Martin.

The newly elected governor was considered by some to be a moderate, while others, especially Democrats, thought him to be a conservative. Vic Meyers was more to the left of the governor, yet he remained popular with much of the electorate.

Vic Meyers put his beliefs into action and managed to enrage Governor Martin. Meyers was vacationing in California, so Martin thought it would be safe to make a rare trip to Washington, D.C. When the lieutenant governor heard the chief executive had left the state, he hurried back to Olympia, preparing to call a special session of the state legislature to consider pension legislation. Governor Martin had to charter an airplane back home to Washington state to stop Meyers. Arthur Langlie, a profoundly religious man, was said to have pledged never to leave the state during the eight years Vic Meyers was his lieutenant governor, for fear of what Meyers might attempt to do.

Meyers won the 1940 election while former U.S. Senator Clarence C. Dill, the Democratic nominee, lost the governorship to GOP candidate Arthur Langlie. Meyers was easily reelected in 1944 and in 1948 won a narrow victory as Governor Mon Wallgren was losing to former Governor Langlie. Meyers was finally defeated after serving twenty years as Washington’s Lieutenant Governor in 1952 while Dwight D. Eisenhower was carrying the state. The people of the Evergreen State were splitting their tickets down the ballot, choosing Democratic Congressman Henry Jackson over incumbent GOP Senator Harry Cain and reelecting Governor Arthur Langlie. Meyers was ousted by Republican Emmet Anderson.

Years later, members of both political parties would remember Vic Meyers as an effective presiding officer. Democrat A. L. Rasmussen remembered many of the rulings made by Lieutenant Governor Meyers still stood as precedents almost forty years after he had left office. Former Governor Albert Rosellini recalled that Meyer was adept at using his wit and humor to diffuse tensions.

When Secretary of State Earl Coe ran for governor in 1956, it left the way clear for Vic Meyers to once again run statewide. “The last time I talked to you people, I asked you to help old Vic out; now I’m asking you to help old Vic back in,” Meyers said. Once again, Washingtonians split their tickets for Eisenhower, but reelected Senator Warren Magnuson over Governor Langley. Meyers won the secretary of state’s office narrowly.

Halfway through his term of office, Meyers became a candidate for Congress, running in Washington’s Third Congressional District. Meyers faced a formidable Republican opponent in Congressman Russell V. Mack. The congressman had been in office since a 1947 special election and had worked hard to entrench himself and had succeeded. While 1958 saw Democrats sweep the midterm elections, Russell Mack was well known for running well ahead of the GOP ticket and beat Meyer badly. It may well be that many of the voters in the Third District thought serving in the House of Representatives was a serious responsibility and believed Vic Meyers did not measure up to that responsibility. In any event, they certainly decided Meyers didn’t measure up to Russell Mack.

Meyers showed no compunction to retire, and the 61-year-old incumbent sought reelection to the secretary of state’s office in 1960. Vic Meyers carried all but a handful of counties in the 1960 election, winning by a majority of more than 76,000 votes.

The end came for Victor A. Meyers when he was rocked by two events. One being a mishandled petition in the secretary of state’s office having to do with placing a gambling initiative on the ballot. The second was an arrest for drunk driving. One additional factor injured Meyers’ standing with the voters when newspapers revealed that the secretary of state’s daughter, brother, sister and niece were all on his payroll. Meyers insisted on going to trial over the drunk driving charge, and while he had an entirely plausible story, the facts of the case caused the judge to find him guilty and fine him.

The mishandled petition on the gambling tolerance referendum produced reams of bad publicity for the secretary of state. A court ordered Victor Meyers to produce the missing documents after the secretary of state had certified the initiative as Referendum 34. The petitions, which had close to 83,000 signatures on them, had been stolen from inside a vault in the secretary of state’s office a week before. A Seattle attorney had sued Meyers for having certified the referendum without having checked the signatures as being valid. It was the first time in 51 years of referenda in Washington state that petitions with signatures had been stolen from the secretary of state’s office. “It was a ghastly experience,” Meyers acknowledged. It certainly damaged his reputation and called into serious question his conduct in the office.

Washington state Republicans selected several attractive young candidates for statewide office in 1964 to compete with aging Democratic incumbents. Vic Meyers faced A. Ludlow Kramer, the scion of a wealthy New York family, who had been elected to the Seattle City Council as a stripling of 29 years of age.

The regular ticket splitting in Washington state occurred yet again in 1964. While Evergreen State voters rejected GOP presidential nominee Barry Goldwater overwhelmingly, they were electing Republican Dan Evans over incumbent Governor Albert Rosellini. Henry Jackson was reelected in a landslide while, at the same time, several highly popular Republican congressmen lost unexpectedly. Vic Meyers lost to Lud Kramer by more than 100,000 votes. In defeat, Meyers had yet another quip: “They finally caught up to me.”

It was the end of Meyer’s long political career. In 1976, Meyers pondered yet another comeback. At 78, Meyers filed to run for the secretary of state’s office once again. The old warhorse’s prospective candidacy fired up the imaginations of young reporters who had not even been born during his first bid for public office. It caused a rush of nostalgia. Vic Meyers thought better of it and withdrew his name. It was good to be remembered while still able to enjoy it.

Meyers died on May 28, 1991.

© RAY HILL