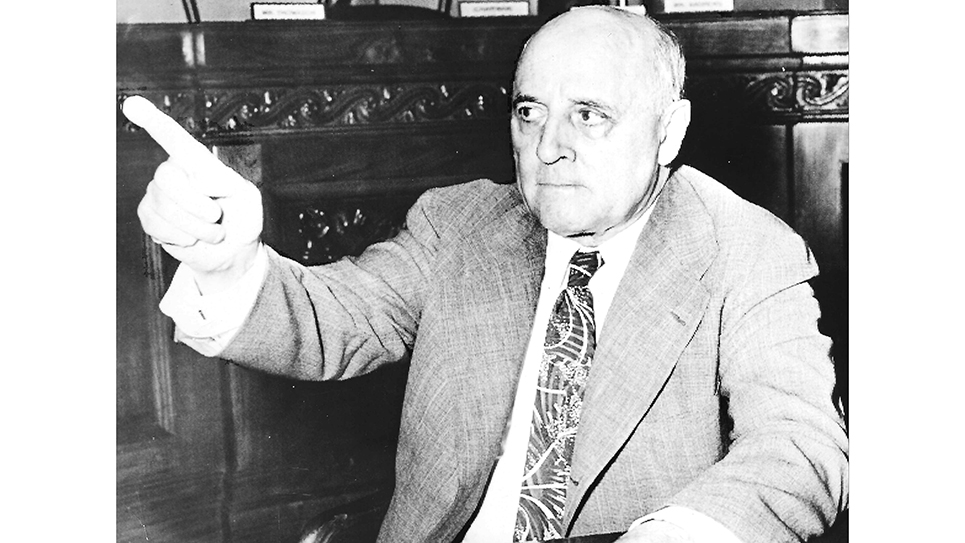

Old Time Democrat: Senator Pat McNamara of Michigan

By Ray Hill

Patrick Vincent McNamara was the kind of Democrat that is almost entirely extinct in today’s world. A traditional, working-class Irish Catholic and local labor leader.

The child of a laborer, McNamara recalled his childhood fondly. “We always had plenty to eat,” McNamara told a reporter years later. “I don’t recall feeling poor. We lived simply. We had lots of fish from the ocean, chickens from the yard, eggs, plenty of milk.” McNamara was proud of his heritage. “I am a first generation American. I’ve always been lucky,” he said.

While the elder McNamara was a good provider and hard worker, McNamara’s father drank, and his drinking made him slur his speech, something the boy loathed. Once spying a bottle of whisky on a table that was two-thirds full, the seven-year-old Pat McNamara astonishingly drank it all. His mother found him lying on the floor and thought he was dead. Still, Mrs. McNamara summoned a doctor who arrived by horse and buggy and looked over what everyone thought was Pat McNamara’s lifeless body. The doctor placed young Pat over a child’s cradle and rocked the boy until he threw up and miraculously came back to life. The future senator never was much of a drinker, according to friends, limiting himself to a cocktail before dinner.

The youngest of eight children, Pat McNamara grew up as a tradesman after dropping out of high school and working as a pipe fitter. At one time, McNamara was employed as the maintenance foreman at the Chrysler plant in Detroit. McNamara became the president of Local 636 of the Pipe Fitters Union in 1937 and retained the post until 1955, when he resigned after having been elected to the United States Senate.

McNamara never lost his labor roots even after becoming vice president and superintendent of construction for the Stanley-Carter Company. McNamara’s first campaign for political office began on the local level when he ran for and was elected to the Detroit City Council. Pat McNamara made the astonishing leap from the Detroit Board of Education to the United States Senate. Former Congressman Neil Staebler of Michigan remembered McNamara as being “almost unique in politics in that nobody ever changed his mind once he had made it up.” Membership in the United States Senate did not change Pat McNamara; he remained blunt and honest to the end of his days. McNamara’s colleague Paul Douglas of Illinois thought there was “no guile” in his friend from Michigan. The Detroit Free Press remembered Pat McNamara as “blunt,” “candid,” and “independent.”

As might be expected from a U.S. senator who rose from the working class, Pat McNamara, throughout his twelve years in the Senate, worked on those issues he thought would improve the lives of the people he represented: better health care for seniors, expanding Social Security, and education. And, of course, coming from labor, McNamara remained one of organized labor’s chief spokesmen in Congress.

When Pat McNamara first announced his candidacy for the Senate, virtually nobody gave him a chance of winning the Democratic primary, much less winning the general election. Blair Moody had been appointed to the U.S. Senate on April 22, 1951, when veteran Senator Arthur Vandenberg died of cancer. Moody was a candidate to succeed himself in the 1952 election, but it was a Republican year, and he lost to Congressman Charles E. Potter. Moody, a prominent journalist, had been appointed by Governor G. Mennen “Soapy” Williams and never stopped campaigning, aiming to unseat Michigan’s other senator, Homer Ferguson, who was one of the more recognizable members of the Senate.

Moody hosted a television show, “Meet Your Congress,” during the interim of his anticipated political comeback. Blair Moody was campaigning hard and had the support of the Williams administration and seemed like a sure winner until he fell ill. The former senator was sent to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with a form of viral pneumonia. Moody, 52, was thought to be recovering when he died from a heart attack.

With their prospective nominee dead, the Williams organization swung fully behind McNamara’s candidacy, quickly quashing any effort to replace Blair Moody with another candidate. Such was the devotion of many Michigan Democrats to the memory of Blair Moody that more than 126,000 Michigan voters voted for him in the primary. Pat McNamara was nominated easily and won the right to face Senator Homer Ferguson. The Detroit Free Press noted McNamara was a “maverick” inside his own party, and one reason 126,000 voters chose to vote for a dead man was because they found the alternative “too hard to accept.” Eventually, McNamara won over most of those who were skeptical through his “likeable Irish outspokenness.”

Ferguson was in a strong position for reelection, having first been elected to the U.S. Senate in 1942, defeating incumbent Prentiss Brown, who had won during the 1936 Roosevelt landslide. Homer Ferguson first came to notice as a crime-busting judge and retained his ability to attract headlines during his Senate career. The whitehaired Ferguson looked every bit the part of a U.S. senator.

Homer Ferguson had run ahead of his party’s ticket to win a narrow reelection in 1948 while much of the GOP ticket was going down to defeat. Republican presidential nominee Governor Thomas E. Dewey carried Michigan largely because Henry Wallace’s third-party candidacy took enough votes away from Harry Truman to tip the state into the GOP column. Senator Ferguson ran ahead of Dewey to beat former Congressman Frank Hook.

During the 1954 election, Senator Ferguson carried an additional burden in the form of Charlie Wilson, President Eisenhower’s secretary of defense. Wilson had been the president of General Electric when Eisenhower made him defense secretary. Charles Wilson is largely remembered for his statement, “What is good for General Motors is good for America.”

As plainspoken as Pat McNamara, Wilson made a highly unfortunate remark, which was allegedly, “While I have sympathy for the jobless and surplus labor areas, I also like bird dogs better than kennel-fed dogs. Bird dogs hunt around for food while kennel-fed dogs sit upon their haunches and yell.” Wilson, who was notoriously anti-union, made the comment during a season of high unemployment in Detroit and must have caused Senator Ferguson to wince. “Mr. Wilson’s remarks are typical of the Dark Age thinking of the Republican Administration,” Pat McNamara said. “Mr. Wilson’s attitude can be compared with Marie Antoinette, the queen of France, who was told the starving people had no bread and said, ‘Let them eat cake.’”

Pat McNamara hammered Senator Ferguson for running on Eisenhower’s coattails yet enjoyed ticking off those instances when the incumbent had not backed the administration. McNamara charged that Ferguson was a slave to the big corporate interests, as evidenced by the senator’s financial backers. Naturally, the Ferguson campaign touted the senator as a nationally recognized legislator of experience while Pat McNamara was a mere local official.

The race was a dead heat until the very last. In the end, Pat McNamara had upset Senator Ferguson, winning by just over 39,000 votes. At the same time, Governor Williams was handily beating the GOP nominee for governor by more than 250,000 votes. Pat McNamara was helped by a huge majority in Wayne County (Detroit) and the big win by Governor Williams, which helped to carry much of the Democratic ticket to victory with him. There were those who believed Charlie Wilson’s kennel-fed dog remark cost Senator Homer Ferguson reelection.

Hard to miss at 6’2 and weighing more than 200 pounds, gray-haired and gravel-voiced from his heavy smoking habit, the 60-year-old senator-elect went to Washington, D.C. One reporter observed that McNamara was “outwardly calm” as he walked down the aisle of the Senate chamber and raised his right hand as Vice President Richard Nixon administered the oath of office. A group of supporters who had been labeled “McNamara’s Band” during the campaign descended upon the Capitol to celebrate the senator’s swearing-in. The group and other well-wishers joined Senator McNamara and his wife in his office. Amongst the visitors were George Meany, head of the American Federation of Labor, and Martin Durkin, the head of the AFL’s plumbers’ union and former secretary of labor under President Eisenhower. Durkin’s tenure in office was one of the shortest in history as he resigned after eight months because the president refused to consider revisions to the Taft-Hartley Act. The visitors going to and from Senator McNamara’s office were a parade of union officials, big and small. The night before taking the oath of office, McNamara and his wife were hosted by the Building Trades Council at a steak dinner at Washington’s elegant Sheraton-Carlton Hotel, attended by approximately 50 persons. McNamara toasted his friends, saying, “There is not a group anywhere in the country less selfish.”

McNamara had been surprised when he first visited his suite in the Senate Office Building, only to discover there was not a single stick of furniture, merely telephones resting on the floor. One enterprising photojournalist took a photograph of the senator-elect talking on the telephone, kneeling on one leg in his still barren office.

The newly sworn-in senator said gruffly he would support President Eisenhower “when I think his policies are right,” but added the president was “minus one with me.” Senator McNamara had not forgotten Eisenhower’s appearance on behalf of Homer Ferguson during the campaign. “He took potshots in three other states, Ohio, Kentucky and Delaware,” McNamara growled, “But he came right to the City Hall steps in Detroit to try to beat me. He failed, so I’m not really happy about it.”

McNamara’s opinion of the president seemed unchanged for the next six years. Loyal Democrat that he was, Senator McNamara campaigned alongside Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson, Senate colleague and vice-presidential nominee Estes Kefauver, and Governor Soapy Williams in Michigan.

Senator McNamara joined four of his liberal colleagues from the West and the North in supporting a “Democratic Declaration of 1957.” The declaration could be summarized as an attempt to bring an end to filibusters inside the Senate and pass a civil rights bill. Hubert Humphrey, McNamara and their colleagues wanted to change the rule requiring a two-thirds vote to end a filibuster and make it a simple majority. That same year, Senator McNamara showed his independence when he privately circulated a letter critical of powerful Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas. It was part of a minor uprising amongst the most liberal members of the Senate who demanded a modification of the Democratic policy in the Senate. LBJ privately denounced them derisively as the “red hots,” but he did alter his course. Senator McNamara was one of the first in Congress to highlight fraud against elderly people through congressional hearings. McNamara also helped to lead the fight for hospital insurance for the elderly through Social Security.

Senator Pat McNamara began his 1960 reelection campaign as a heavy favorite, but an energetic and well-financed campaign by Congressman Alvin Bentley made it a race. A determined millionaire businessman, Bentley learned Polish and Hungarian and managed to charm many ethnic audiences in ordinarily Democratic wards. The House member most seriously wounded when Puerto Rican nationalists opened fire on a defenseless House Chamber, Alvin Bentley, liked to show his bullet-riddled wallet from that day to audiences as he campaigned. McNamara was also having trouble with the mercurial Jimmy Hoffa, who marked the senator for political oblivion, despite McNamara having been what TIME magazine noted was a “shameless apologist” for the Teamsters Union during the congressional investigation into Hoffa and his organization. McNamara won a close contest by 120,000 votes out of approximately 3.2 million cast.

Seventy-one years old in 1966, Senator Pat McNamara was ailing. The senator had previously announced he would not be a candidate for a third term and entered Bethesda Naval Hospital on March 11, 1966, for treatment of a blood clot in his lung. McNamara never left the hospital, dying of a stroke on April 30.

© 2025 Ray Hill