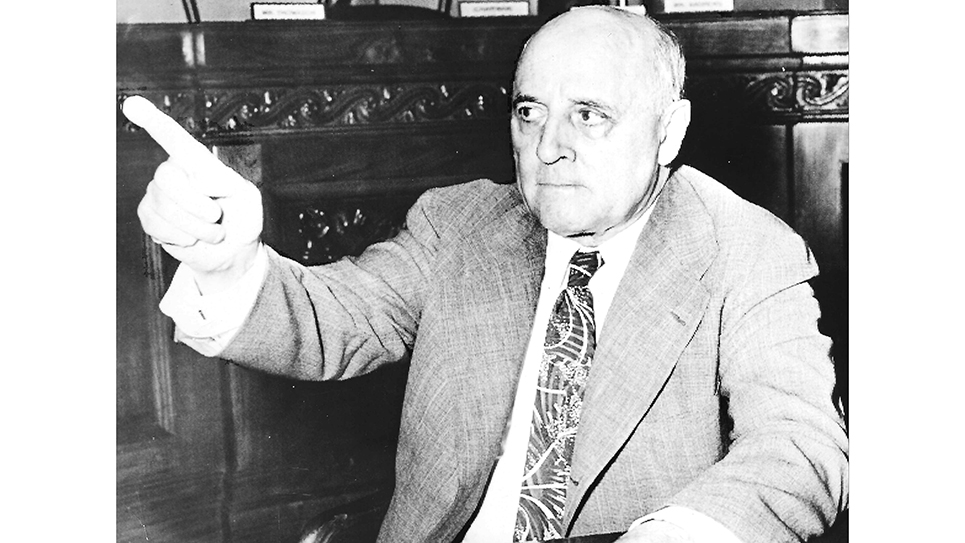

William O. Bradley of Kentucky

By Ray Hill

William O’Connell Bradley was the first Republican to serve as governor of Kentucky. Bradley had a long and notable political career, albeit with mixed results as Kentucky remained a mostly Democratic state. During his zenith, many media outlets considered Kentucky less a border state than a southern state. William O. Bradley was one of the few Republicans to flourish in a border or southern state.

An impressive-looking man with a full, clean-shaven face and somewhat portly build, Bradley was known as a powerful orator. William O. Bradley had been something of a prodigy; his father was one of the leading criminal defense attorneys in the Bluegrass State, and the elder Bradley’s financial success allowed him to have his son schooled privately, as well as employ tutors. William was the only surviving son and had five sisters. At 14, W. O. Bradley left school without his father’s permission to join the Union Army during the Civil War twice. Both times, Robert McAfee Bradley had his son severed from the service because of his being so young. At the time, law students didn’t necessarily have to attend law schools or universities; one could “read” the law under the supervision of a qualified attorney before taking the bar examination. Bradley was fortunate enough to study the law under his father’s tutelage and wanted to take the bar exam at 18, although state law required one to be 21 to do so. The Kentucky legislature passed a special act permitting William O. Bradley to be examined by two sitting judges of the Circuit Court and found him to be competent in the law. Bradley passed and joined his father’s firm in 1865.

Five years later, William O. Bradley began his political career, running for and winning election as the prosecuting attorney for Garrard County. Two years later in 1872, the ambitious young man made a bid for the U.S. House of Representatives and won the Republican nomination for Kentucky’s Eighth Congressional District. The GOP nomination was largely an empty honor inasmuch as the Eighth District was heavily Democratic. Bradley faced former Circuit Judge Milton John Durham in the general election and lost.

Although young, Bradley was widely admired by Kentuckian Republicans who liked his fighting spirit and enjoyed his ability to make a fine speech. Indeed, the “matchless voice” of William O. Bradley would be long remembered by Kentuckians. Bradley was well able to articulate his point of view and that of his party on a wide array of issues. In 1875, United States senators were still elected by the members of the state legislatures. Kentucky Republicans selected William O. Bradley as their nominee that year and the young attorney won the vote of every GOP member. It was largely a symbolic honor as Bradley was not even 30 years old, the age required by the Constitution to hold a seat in the U.S. Senate.

Bradley was persistent in his pursuit of public office and tried once again for Congress, challenging Congressman Milton Durham in 1874. William O. Bradley demonstrated an ability to win votes, running well ahead of his ticket, but he was still a Republican mired in a very Democratic district. Bradley’s speaking ability attracted notice outside his own state of Kentucky, and he was selected to speak before the 1880 Republican National Convention. That year, Ulysses S. Grant was proposing to come out of retirement and seek an unprecedented third term as president of the United States. Grant was by no means a unanimous choice of Republicans, as there were numerous delegates opposed to the former general’s nomination. Grant’s nominating speech was made by the famous and flamboyant Senator Roscoe Conklin of New York, and the main seconding speech was made by young William O. Bradley of Kentucky. Amongst the delegates and Republican leaders, Bradley’s speech made perhaps a deeper impression than had Conkling’s. The Louisville Courier-Journal noted that, at least in terms of “metaphors and gyrations in the clouds with oratorical flashes the Bradley speech surpassed that of Conklin.”

In 1887, Bradley won the Republican nomination to run for governor of Kentucky. The 40-year-old GOP candidate faced a formidable foe in Simon Bolivar Buckner, a silver-haired and impressively white-bearded former Confederate general. Although Kentucky had not seceded from the Union during the Civil War, its voters had a habit of sending former Confederates to Congress and electing them as the state’s chief executive, a practice Bradley roundly criticized. Bradley lambasted former democratic administrations for big and wasteful spending and a stale state economy.

The two candidates appeared together only once during the campaign after agreeing to several joint debates. General Buckner got to his feet and demanded to know if Bradley had made the accusation that a former governor had written a speech he had given. Bradley readily admitted he had been told as much and had repeated it before an audience. Buckner snapped that the accusation was not true and promptly announced he felt free to withdraw his acceptance of further joint speaking appearances. Bradley lost the general election but made the best showing of any Republican candidate at that time.

William O. Bradley had constantly assailed the state’s finances and the handling of those finances during the gubernatorial election. Bradley’s insistence for state officials to examine the books of the treasurer was picked up by members of the state legislature. Governor Buckner had the accounts audited and the people of Kentucky were astonished when the state treasurer, James William “Honest Dick” Tate, disappeared with $250,000 (more than $8 million today) of the taxpayers’ money. Tate did indeed have a reputation for honesty, but he boarded a train bound for Cincinnati and was never seen again, leaving his wife and daughter in Kentucky. As best as could be ascertained, a combination of embezzlement, thievery, and barely any bookkeeping had occurred during Tate’s administration as state treasurer.

Bradley’s having brought the issue to light did his own reputation no damage and left Kentucky’s Democrats badly humiliated. The small Republican minority in the legislature nominated William O. Bradley as their candidate for the United States Senate once again in 1888, but he lost to the Democratic nominee. Bradley’s successful opponent in that senatorial contest, James B. Beck, apparently had no bad feelings for his Republican competitor. It was Senator Beck who recommended William O. Bradley for a post in the administration of GOP President Benjamin Harrison. Bradley was offered the ambassadorship to Korea, but the Kentuckian preferred to remain at home.

William O. Bradley announced he would make another bid for the governorship in 1895, and he seemed to be the nearest thing to a unanimous choice by Kentucky Republicans. Bradley was nominated and embarked upon a heated campaign against the Democratic nominee, Parker W. Hardin, Kentucky’s State Attorney General. Democrats across the country were deeply divided, both nationally and in many states, over the “free silver” question that would bring an obscure Nebraska congressman to national prominence and a presidential nomination a year later. President Grover Cleveland, as well as his Secretary of the Treasury, John Carlisle, a Kentuckian, were both adamantly opposed to free silver, insisting on “sound money,” meaning the gold standard. Hardin won the Democratic nomination for governor while many of Kentucky’s most influential Democrats were sound money men. Attorney General Hardin pledged to support the platform adopted by the state convention, which was a sound money platform. Once he had the nomination in hand, Parker W. Hardin came out with a full-throated endorsement of free silver. In part, Hardin retreated to his original position to fend off the Populist gubernatorial candidate from taking away votes in rural counties. Bradley ran hard in the general election, and Hardin was pressed, eventually having to resort to reminding voters of the “carpetbaggers” of Reconstruction following the Civil War, as well as the charge that electing a Republican would mean the domination of the Bluegrass State by Blacks. It availed him little as William O. Bradley won the general election.

Almost immediately, Governor Bradley was confronted with an out-of-control session of the state legislature, which became deadlocked while trying to elect a United States senator. Once again, Democrats were divided by the money question and as incumbent Senator Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn was a strong supporter of free silver, the “gold bug” Democrats in the legislature refused to reelect him. As the days passed, the situation grew worse with some Democrats carrying guns and attempting to keep Republican legislators from entering the House Chamber. The threat of violence was escalating quickly, and Governor Bradley called out the state militia to maintain order. That caused some tempers to flare with a few Democrats attempting to censure the governor, fine him, and sentence him to a six-month term in jail. Governor Bradley was forced to call a special session of the legislature to resume the voting to elect a United States senator.

It took 112 ballots before the legislature picked a senator. Despite the majority Democrats enjoyed, William J. Deboe, a member of the state Senate and a Republican, was elected. Deboe was the first Republican to be sent to the United States Senate from Kentucky.

During his time as governor, William O. Bradley was a fierce opponent of lynchings and insisted that violence against Black people be prosecuted. When President Grover Cleveland left office and was replaced by Republican William McKinley (who defeated free silver advocate William Jennings Bryan) in 1897, Kentucky Democrats resolved to do nothing to advance Governor Bradley’s agenda. Reinforced by big majorities won in Kentucky 1897 off-year elections, petulant Democrats made life as miserable as possible for the governor. When Bradley pointed out the deficiencies of the governor’s mansion, which was in desperate need of repairs and renovations, the legislature ignored him. A resulting fire from a faulty fireplace flue gutted much of the mansion, causing the governor to move his family in with neighbors before he resided in a hotel. The Democrats were not going to lift a finger to accommodate a Republican governor.

Following his term as governor, William O. Bradley was once again the GOP nominee for a seat in the United States Senate in 1900. After experiencing some success, Kentucky Republicans began fighting with one another when they were a distinct minority in the Bluegrass State. Nationally, the former governor was still highly regarded. The Kentucky Advocate remembered Bradley’s word “was law” during the presidential administration of William Howard Taft as to the distribution of appointments and patronage in Kentucky.

In 1907, Republicans were successful in electing August Willson as governor, and the GOP nominated William O. Bradley for the Senate once again in 1908. Once again, Democrats engaged in a bare-knuckled political brawl. The impediment was the candidacy of former governor J. C. W. Beckham, a Democrat who drank “wet” but voted “dry.” Former Governor William O. Bradley was an opponent of prohibition, and after two months of stalemate, four Democratic legislators crossed over, tipping the election to William O. Bradley. After repeated attempts, W. O. Bradley had finally achieved his cherished dream of sitting in the United States Senate.

Bradley announced he would not be a candidate for reelection, although the 1914 election would be the first time the people of Kentucky chose their own U.S. senator by direct election. Bradley was intending to retire from public life. The same day the senator made his announcement, he fell while attempting to catch a streetcar and seriously hurt himself, breaking at least two fingers and gashing his forehead. Initially, it was thought Bradley might have suffered internal injuries. Within a couple of days, he was back in his office, although he soon complained of feeling poorly again. A few days later, while dictating to a secretary, Senator Bradley was gripped by a “painful seizure” and taken home and put to bed. The senator never got out of that bed, already suffering from prostate and kidney ailments, W. O. Bradley died May 23, 1914. William O. Bradley was 67 years old, which is relatively young, but it is interesting to remember that it had been almost 40 years since he had first been nominated to serve in the United States Senate.

© 2025 Ray Hill