Michigan’s Governor

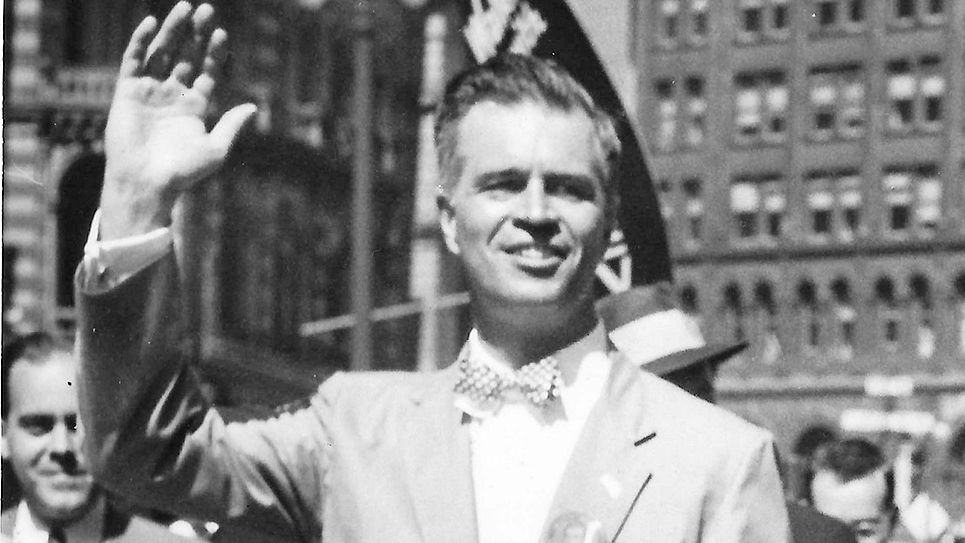

G. Mennen Williams

By Ray Hill

Gerhard Mennen Williams’ name is a reminder of his good luck in having been born into a family fortune. His grandfather, Gerhard Mennen, a German immigrant, started a business selling talcum powder, which at the time was a novelty. That grew into a corporate giant that produced men’s care products and was later sold to Colgate-Palmolive. Williams’ mother, Elma, was Gerhard Mennen’s daughter, and she named her son for her father. Williams was better known to his friends as “Soapy,” a nickname derived from his family’s business products. Williams’ trademark was a green bowtie with white polka dots and was so well known that campaign buttons and tabs were distributed during his many campaigns with that emblem, and people immediately recognized its significance. Williams almost always signed his name in green ink.

Williams dominated Michigan’s politics for more than a decade, elected governor six times when the term of office was two years. Williams used his governorship to take control of Michigan’s Democratic Party and forged a mutually beneficial alliance with Walter Reuther, who built the United Auto Workers into a formidable force, especially in Michigan. At one time, Reuther was simultaneously president of the UAW and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Suffice it to say, Walter Reuther was one of the most powerful individuals in organized labor, if not the most powerful.

When Williams began his first campaign for governor in 1948, he was a boyish-looking young man of 37 years. As a successful and popular chief executive of a pivotal state, Mennen Williams was floated as a presidential and vice-presidential possibility several times. That was certainly true in 1956, and the governor told the press he felt “no compelling reason to run for the vice presidency,” but added, “I am not prepared to say I wouldn’t accept.” Williams had been featured on the cover of the most widely read news magazine in the world, TIME, in 1952, green polka-dotted bowtie, big grin and all.

Williams attended law school, graduated, and began the practice of law. He married Nancy Quirk, and the couple had three children. Like most of the “Greatest Generation,” Soapy Williams served in the armed forces during the Second World War. Williams was an air combat intelligence officer in the U.S. Navy for four years, rising to the rank of lieutenant commander.

In 1948, Williams launched his candidacy for the Democratic nomination for governor, facing two opponents in the primary. The strong support of organized labor helped the youthful contender to narrowly win the Democratic primary by just over 8,000 votes. Labor had been divided between Williams and Victor Bucknell, who enjoyed the support of the Teamsters’ Union. Williams faced Governor Kim Sigler in the 1948 general election. Sigler had been elected in 1946, a great year for GOP candidates, and had been hailed for his role as a special prosecutor who cleaned up corruption in the state legislature.

Sigler was seeking reelection in what was widely thought to be a banner year for Republican candidates. As it turned out, it was quite the opposite. Soapy Williams upset the incumbent, winning by more than 160,000 votes. Williams’ brother, Dick, gifted the governor-elect with a green and white polka-dotted bowtie, which he wore at his inauguration. That was how his trademark was born.

Throughout his tenure as Michigan’s chief executive, Williams sought to work with state legislators, oftentimes comprised of a majority of Republicans. “The people of Michigan expect us to work together,” Governor Williams told legislators. As governor, Williams never hesitated to veto bills he believed to be against the public interest.

Williams built a formidable political organization based in Detroit through organized labor and an upstate combine of grassroots supporters, which provided healthy majorities for the governor and many Democratic candidates.

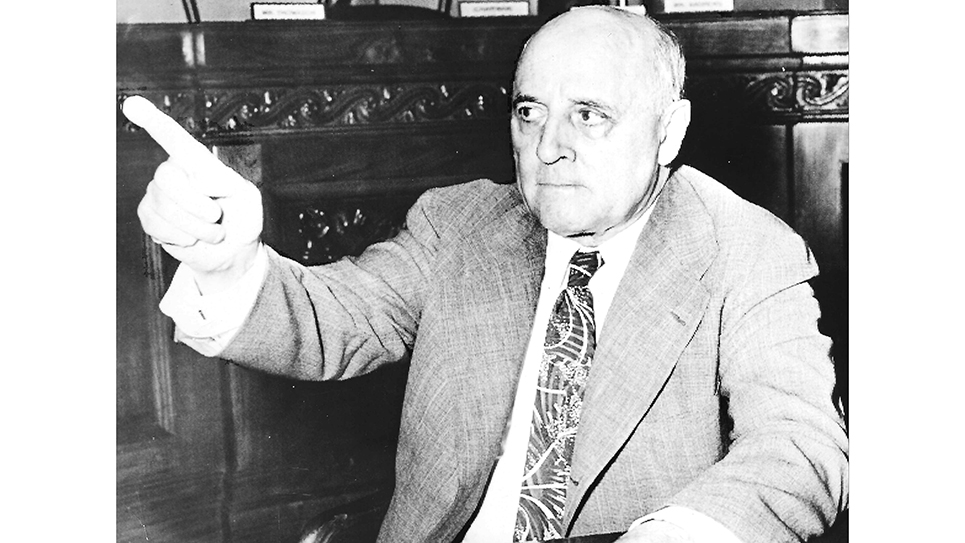

Williams faced a tough reelection campaign in 1950 when Republicans called former Governor Harry F. Kelly out of political retirement. Kelly had been elected governor in 1942 and reelected two years later, serving throughout most of World War II. Unfortunately, the GOP was divided, and Kelly faced a crowded primary field consisting of the secretary of state, a former lieutenant governor, and a sitting congressman. Kelly proved to be a highly popular candidate in the general election, as many Michiganians remembered their wartime governor fondly. The result was a nail-biter of an election, which Soapy Williams won by 1,154 votes out of more than 1.8 million cast. Kelly ran for a seat on Michigan’s State Supreme Court in 1954 and retired in 1971, the same year Soapy Williams was elected to the high court.

Governor Williams faced another difficult campaign two years later when Dwight D. Eisenhower headed the national GOP ticket. Williams beat his Republican opponent by 8,618 out of quite nearly 3 million votes cast. Williams managed to run well ahead of his ticket as Eisenhower won Michigan easily, and Senator Blair Moody lost to Republican Charles E. Potter.

Seeking a fourth term in 1954, Williams led a highly successful Democratic ticket. Patrick V. McNamara upset GOP Senator Homer Ferguson and Philip Hart, a law school classmate and close friend of the governor’s, was elected lieutenant governor of Michigan. Williams beat his Republican opponent by more than 250,000 votes.

By the time Mennen Williams announced his candidacy for a fifth two-year term in 1956, he had been governor of Michigan longer than any other person. Williams’ last administration was perhaps the most difficult of his career. The State of Michigan was experiencing serious financial difficulties, especially after the GOP majority in the state Senate refused to approve the governor’s proposed $50 million bond issue, which was intended to meet state payrolls and other “pressing expenses.”

TIME magazine pinned much of the blame for Michigan’s fiscal woes on Governor G. Mennen Williams, noting the increasing “welfare” programs passed by the governor over the preceding decade “gobbles up a lot of revenue.” Michigan’s budget woes were exacerbated by the fact that the country was in a recession; the state had been hit by unemployment, which was especially acute in the automotive capital of Detroit. The state budget was further deflated by the slowdown in the collection of the 3% sales tax. The State of Michigan’s estimate of sales tax collections had proven to be $43 million less than had been anticipated, leaving a serious hole in the budget.

The governor was barred by state law from borrowing more than $150,000, and he sent personal letters to the heads of 23 large corporations. That letter asked the corporate executives to pay some $28 million (almost $241 million today) in business taxes in advance. TIME acknowledged most of the corporate business leaders disapproved of Governor Williams’ ‘big-spending habits,” as well as his alliance with Walter Reuther and organized labor. Most of those asked for help by the governor came through for the people of Michigan; as TIME noted, “General Motors alone put up $13 million,” but the news magazine also acknowledged the obvious, stating, “But this bailout only postponed the crisis.”

The governor and the Republican-led state Senate were at odds on how to make up the deficit. Williams supported “a progressive state income tax on middle and upper incomes and a new 5% levy on corporation profits.” Opponents cried that the governor’s proposed solution would worsen Michigan’s already severe problem of attracting new businesses, much less keeping them. The Republicans in the state Senate preferred increasing the sales tax to 4%, a remedy “adamantly opposed” by the governor.

During Williams’ time as governor, Democrats won both of Michigan’s seats in the United States Senate, and he had his eye on the 1960 presidential nomination. Realizing he could not beat John F. Kennedy, Governor Williams fell in line behind the candidacy of the senator from Massachusetts. Retiring as governor, Williams accepted an appointment from President Kennedy as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs. It was an important assignment, especially during a time when many African nations were emerging from colonial rule by various European countries.

After his service during the administrations of Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, Williams itched to get back into the political limelight once again. Sporting his green and white polka-dotted bowtie, the former governor was spotted in the Lansing State Capitol, shaking hands with everyone he met. One legislator, a Democrat, cried, “Boy! It’s just like old times!” Williams was a candidate for the United States Senate to succeed Pat McNamara, who was seriously ailing. The 71-year-old McNamara had just announced he would not run for a third term. Williams pounced on the opportunity to run and became the favorite for the Democratic nomination almost instantly, but the former governor encountered stiff opposition inside the primary. Jerome Cavanaugh was the mayor of Detroit and had just won a second term the previous year with quite nearly 70% of the vote and was blatantly eager for higher office. Cavanaugh was 38 years old when he entered the senatorial contest, just a year older than “Soapy” Williams had been when he ran his first statewide race. The Democratic primary was contentious, but Cavanaugh could not overcome Williams’ advantage in statewide recognition nor the financial resources the former governor could command from organized labor and his network of supporters and friends. Williams in fact trounced Cavanaugh in Wayne County, where Detroit is located. The former governor won the primary election with 60% of the vote.

The 1966 senatorial race in Michigan was a reminder that success in politics oftentimes depends on timing and good luck. Senator McNamara was being treated at Bethesda Naval Hospital when he died of a stroke on April 30, 1966. Vacancies in the U.S. House of Representatives are filled by special election; senatorial vacancies are filled by governors. The governor of Michigan at the time was George Romney (father of Mitt), who was highly popular in the Wolverine State. Romney appointed Congressman Robert P. Griffin, who was already running for the Senate, to fill McNamara’s seat. That appointment enabled Griffin to run as an incumbent. Having already served as a congressman since 1957, Griffin was an experienced and shrewd campaigner. Williams was also no longer the boy wonder of Michigan politics, and many voters still remembered the fiscal distress during his last administration as governor. Many political observers thought Williams had left the governorship at precisely the right time, as his popularity was diminishing. Governor Williams had not led the ticket in 1958; in fact, he ran fifth amongst the Democratic candidates who won.

1966 was a good year for Republicans following the debacle of 1964. Bob Griffin won a decisive victory over former Governor G. Mennen Williams. Griffin ran far ahead of the usual GOP percentage in heavily Democratic Wayne County and won by almost 300,000 votes.

The loss of the 1966 election did not end “Soapy” Williams’ public service, nor did it close his political career. Williams was appointed ambassador to the Philippines by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968, a post he held until he was replaced the following year by Richard Nixon. Williams returned home to Michigan and mounted a campaign to serve on the state Supreme Court in 1970. Williams was elected and served until his retirement in 1987; Williams was the chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court in 1983. Michigan’s State Supreme Court became a final resting place for many former officeholders, including former Governor John Swainson, a Democrat, as well as former U.S. Senator Robert Griffin, who had lost a reelection bid in 1978. Interestingly, it was Bob Griffin who succeeded Williams on the Michigan State Supreme Court. Williams served two eight-year terms on Michigan’s high court.

Justice Williams died at age 76 in Detroit on February 2, 1988, from a massive cerebral hemorrhage. Williams had been in excellent health prior to his death. Suddenly not feeling well, Williams went to bed, where he later suffered a stroke.

Williams’ trademark bowtie was used by the Detroit Free Press in a moving cartoon tribute, which was a drawing of a large bowtie; the polka dots had been replaced by small hearts.

© 2025 Ray Hill