In 1945 Senator Kenneth McKellar was seventy-six years old and had served in the United States Senate for twenty-nine years, longer than any other Tennessean. McKellar was at the peak of his influence and power in the Senate. He was the Chairman of the most powerful Senate Committee, Appropriations, through which every dollar spent by the Federal government had to be approved. To add to his prestige, McKellar had also been elected President Pro Tempore of the United States Senate by his colleagues.

President Franklin Roosevelt had asked E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political organization, to pay a call at the White House. The purpose of Roosevelt’s summons was to discuss the political future of Kenneth McKellar. FDR, all too aware of McKellar’ power inside the Senate, urged Crump to refuse to support McKellar for reelection in 1946. Roosevelt was anticipating trouble from the irascible Tennessean in the modern post world United States and thought McKellar might choose to retire without the support of Crump and the Shelby County machine. Roosevelt told Crump McKellar could not be reelected. Crump did what few people had the nerve to do to Roosevelt’s face and flatly told FDR he was wrong. Crump said not only would McKellar run again in 1946, but that he would be reelected.

Roosevelt himself didn’t live to see the end of World War II, much less the post-war era. FDR was dead within weeks of his conference with the Memphis Boss. Ironically, McKellar went to Hyde Park for the late President’s funeral services.

FDR’s successor, Harry Truman, helped to increase McKellar’s prestige back home in Tennessee by inviting him to sit in on Cabinet meetings. McKellar was virtually Acting Vice President of the United States for two years and received the vice presidential salary and limousine.

Senator McKellar suffered a loss in 1945 that would profoundly affect him personally, as well as the operation of his Senate office. In December of 1945, D. W. “Don” McKellar, the Senator’s long-time Secretary and younger brother died of pneumonia. Although Don was apparently suffering from lung cancer, Senator McKellar himself was unaware that his brother’s condition was serious. McKellar was on a train headed home to Tennessee when he received word of Don’s passing. For the next several weeks, McKellar was inundated with letters of condolence and sympathy cards. Don was well known and very well liked in Tennessee and several newspapers published editorials expressing sympathy at McKellar’s loss. Don McKellar had been especially effective in getting things done for Tennessee and Tennesseans; even though McKellar could hire another Secretary or Chief of Staff, the loss of his younger brother lessened the effectiveness of the vaunted McKellar office.

Don’s widow, Janice McKellar, had been working for Senator McKellar since the 1920s and the two had eventually married. McKellar refused to discharge one or the other, although Janice was terribly upset after Drew Pearson, who had a national newspaper column and radio show, launched an attack on the Tennessean for nepotism. McKellar himself usually ignored charges of nepotism, but retaliated by taking the Senate floor to denounce Pearson. McKellar was hardly the only Washington politician who hated the muckraking columnist. Both Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman loathed Pearson and when Wisconsin demagogue Joe McCarthy physically attacked Pearson at an exclusive Washington club, even Arthur Watkins, the dour Mormon Senator from Utah, expressed approval. President Truman routinely called Pearson “a son-of-a-bitch” at the best of times.

McKellar’s speech on the Senate floor took the hide off the amused Pearson. The Tennessean reached new heights in describing Pearson as a professional liar. Pearson had always found McKellar an inviting target and enjoyed referring to the McKellar temper and his supposedly insatiable appetite for political patronage and penchant for nepotism. Speaking on the Senate floor for more than an hour, McKellar discussed the attributes, or lack thereof, of the “human skunk” Drew Pearson. Referring to Pearson as a liar at least twenty-three times in his speech, McKellar said Pearson was, “an ignorant liar, a pusillanimous liar, a pee wee liar.” Hardly done, Senator McKellar went on to say, “When a man is a natural born liar, a liar during his manhood and all the time, a congenital liar, a liar by profession, a liar for a living, and a liar in the attempt to amuse… a liar in the daytime, and a liar in the nighttime, it is remarkable how he can lie…”

Pearson had also revived a story about McKellar’s dispute on the floor of the Senate with the late New York Senator Royal Copeland. Heated words had been exchanged by the two lawmakers and McKellar was supposedly so angry, he pulled a knife and charged the New Yorker. The knife in question was a tiny pocketknife attached to McKellar’s watch chain. Most of McKellar’s colleagues found the tale of McKellar’s knife quite funny and they certainly enjoyed his public flaying of the hated Drew Pearson. Writer Allen Drury, then a young reporter, recorded in his journal watching Virginia Senator Harry Byrd began to grin as McKellar denied ever having pulled a knife on a colleague and Byrd poked Missouri Senator Bennett Champ Clark in the arm, his grin becoming wider.

McKellar concluded that Pearson was a “…revolving, constitutional, unmitigated infamous liar, this low-lived, double-crossing dishonest, corrupt scoundrel who claims to be a columnist.”

Pearson’s charges did little to affect McKellar’s popularity in Tennessee, which was enhanced by Senator McKellar’s importance in the nation’s Capitol. As E. H. Crump had predicted to President Roosevelt, McKellar intended to seek a sixth term in the United States Senate in 1946.

Unlike 1940 when McKellar had drawn only nominal opposition, there were stirrings in Tennessee that Chattanooga Congressman Estes Kefauver might challenge the venerable old man. Kefauver soon decided he could not beat McKellar and the Senator sarcastically snorted that he understood Kefauver had bowed to the pleas inside his own Congressional district that he run again for Congress. Yet McKellar did draw a serious opponent in the person of Edward Ward “Ned” Carmack of Murfreesboro. Carmack had a name famous in Tennessee politics as his father, a fiery red-headed orator and writer, had served in both the House of Representatives and the United States Senate. The senior Carmack had been gunned down in the streets of Nashville and an imposing statue of Carmack guarded the grounds of the Capitol in Nashville. Ned Carmack himself had long aspired to elected office, declaring himself as a candidate for Congress, United States Senator and governor at one time or the other. Carmack had run only one campaign, challenging Tennessee’s junior U. S. Senator Tom Stewart in 1942. Ned Carmack proved to be an effective campaigner and had actually beaten Stewart until the returns from Shelby County were counted, giving Stewart another term, a fact which mortified Boss Crump.

The McKellar – Crump alliance had dominated Tennessee politics almost completely since 1932 and opponents took heart from Carmack’s announcement he would challenge McKellar. Former Governor Gordon Browning, although still in Europe with American armed forces occupying Germany following World War II, consented to have his name entered in the gubernatorial contest against incumbent Jim Nance McCord. A ticket comprised of Senator McKellar, Governor McCord and young Andrew “Tip” Taylor for the Tennessee Public Service Commission was formed to face Carmack and Browning.

Senator McKellar was frequently ill during 1946 and there was a constant barrage of announcements emanating from Washington that he would soon be home to open his reelection campaign, but many of McKellar’s supporters, realizing he was often sick, urged him to remain in the Capitol. The heat of the Tennessee summer that year was absolutely fierce and a constant stream of letters from friends assured McKellar he was as politically strong as ever with his people.

With Senator McKellar staying in Washington, D. C., much of the campaign fell on the shoulders of Governor McCord. McKellar continued the pretense that he might return to Tennessee at any moment for a whirlwind campaign, but he never made a single personal appearance for his own reelection.

The Tennessee Society, a group of Tennesseans living in Washington, D. C., sponsored a dinner honoring McKellar at the elegant Mayflower Hotel on April 17, 1946. The timing of the event was hardly coincidental and was heavily covered in both the Tennessee and national press. Much of official Washington turned out for the dinner and Attorney General Tom Clark of Texas served as the Master of Ceremonies for the evening. The Chaplain of the U. S. Senate, Frederick Brown Harris, gave the invocation while Nashville Congressman Percy Priest welcomed the guests. The primary address of the evening was given by Alabama Senator John H. Bankhead, II, who had been McKellar’s college roommate at the University of Alabama decades before.

As guests dined upon an elaborate menu of grapefruit ambrosia, cream of fresh mushrooms, and an entrée of breast of chicken covered with Southern-style ham, peas and candied sweet potatoes, a surprise guest appeared. President Harry Truman entered the ballroom and made a few remarks praising the old Tennessean. A clearly delighted McKellar described the event as one of the greatest of his life.

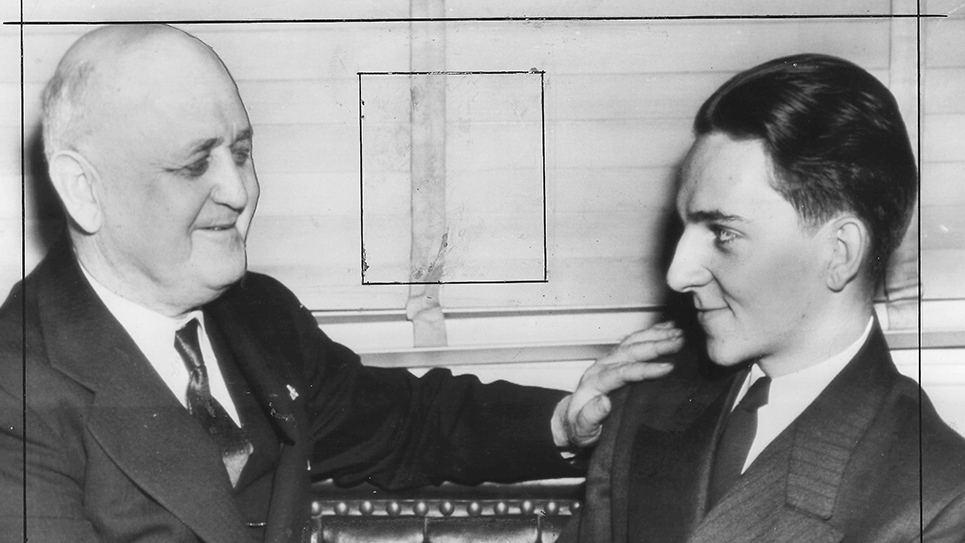

Pictures of a beaming President Truman and Senator McKellar appeared in Tennessee newspapers and the impressive list of prominent officials honoring McKellar was not lost on the people of Tennessee. Ned Carmack gamely campaigned all across Tennessee, attacking Senator McKellar and accusing him of hindering the Tennessee Valley Authority. Even without once returning home to show himself to the voters, McKellar beat Carmack decisively. Governor McCord likewise defeated Gordon Browning who, like McKellar, was not in Tennessee to campaign on his own behalf.

It was to be the last victory of the McKellar – Crump alliance in Tennessee.