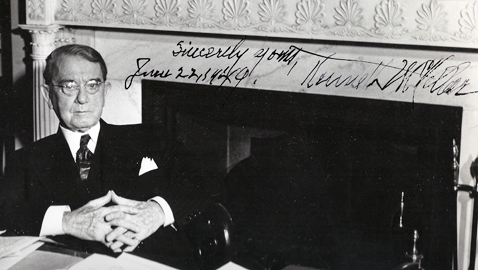

An autographed photo of U. S. Senator Kenneth McKellar from 1949 from the author's personal collection.

With President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan, World War II came to an end. The American people were tiring of rationing and the deprivations brought about by the war effort. Change could not come fast enough to suit most people and in the 1946 elections, Republicans waged a clever campaign taking advantage of the dissatisfaction felt by folks. Campaigning on a slogan of “Had Enough?” Republicans won enough seats to control Congress. Numerous long-time incumbents tasted defeat that year and the remnants of the once powerful isolationist block were virtually wiped out of existence. Senator Burton K. Wheeler, the Montana maverick, lost the Democratic primary in his home state; Henrik Shipstead, first elected to the United States Senate as a Farmer-Labor progressive, was defeated in the Republican primary and the old Norwegian complained it had been his being one of two senators voting against U. S. entry into the United Nations that had caused him to lose his seat. David I. Walsh, the first Irish Catholic ever to be elected governor and U. S. Senator from Massachusetts was upset by Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Progressive Robert M. LaFollette, Jr. of Wisconsin lost his primary to Joe McCarthy, a defeat that would cause LaFollette to commit suicide some years later.

Democrats lost eleven seats in the United States Senate to Republicans in 1946; with the GOP having control of both Houses of Congress, Kenneth McKellar lost his Chairmanship of the Senate Appropriations Committee to New Hampshire Senator Styles Bridges.

President Truman’s own personal popularity had plummeted, causing Arkansas Senator J. William Fulbright to suggest that Truman appoint Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg as Secretary of State and resign, letting the GOP take responsibility of governing the nation. That particular suggestion caused Truman to snap Fulbright should have been named “Halfbright.”

Few thought Truman could be reelected in 1948 and the President faced rebellions inside his own party on not one flank, but both his left and right flanks. Henry Wallace, FDR’s Vice-President from 1941-45, had been removed from the Democratic ticket in 1944 to be replaced by Harry Truman. Franklin Roosevelt had reshuffled his Cabinet to make a place for Wallace as a consolation prize, making Wallace Secretary of Commerce. Wallace remained in the Cabinet for a time after Truman succeeded to the presidency following FDR”s death. Wallace proceeded to give speeches critical of American foreign policy, which irritated Secretary of State James F. Byrnes and infuriated President Truman. Wallace urged closer American cooperation with communist Russia, at a time when the Cold War was as cold as the reaches of outer space. The Russians had clearly not kept the agreements made by dictator Josef Stalin during the war, nor had they kept the agreements made following World War II. Henry Wallace was not only denouncing American foreign policy, he was denouncing Harry Truman’s foreign policy and the little man from Missouri had no intention of tolerating Wallace’s insubordination. Truman told Wallace to stop making speeches about foreign policy and when Wallace ignored the order, Truman fired him from the Cabinet. Wallace was soon campaigning as a third party candidate, attacking Truman from the left.

The uprising inside the Democratic Party on the right came largely from the South, which objected to Harry Truman’s civil rights policies. No one was more upset by Truman’s civil rights stance than E. H. Crump, leader of the Shelby County political machine. When the Democratic Party adopted Truman’s civil rights policies as part of the platform at the 1948 convention, most Southern delegates walked out. Bolting Southerners formed the State’s Rights Party, nominating South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond for President and Mississippi Governor Fielding Wright for Vice President. Crump soon decided he would support the “Dixiecrats” and leave the national Democratic Party. Senator McKellar, while having several grudges to nurse at the hands of President Truman, was horrified at the prospect of leaving the Democratic Party and refused to follow Crump’s lead. Crump had also refused to back Senator Tom Stewart for reelection, allowing Congressman Estes Kefauver to win the Democratic nomination. Were that not bad enough, former Governor Gordon Browning had wrested the gubernatorial nomination away from Jim McCord. Despite detesting both Browning and Kefauver, McKellar loyally announced his support of the entire Democratic ticket, from President Truman down to the local level.

The split in the Democratic Party gave hope to Republicans nationally, as well as in Tennessee. For the first time in many years, Republicans in Tennessee felt they had a chance to elect candidates statewide. Roy Acuff, the popular country music star, had waged a quixotic campaign for governor in 1944, but was running hard in 1948. Former First District Congressman B. Carroll Reece believed he had an opportunity to win a seat in the United States Senate and challenged Estes Kefauver in the general election. Reece was a former Chairman of the National Republican Committee and had presided over the GOP sweep of Congress in 1946.

Following the bitter primary election and with Crump’s defection to the Dixiecrats, Tennessee Democrats were soon alarmed to notice Roy Acuff was drawing enormous crowds to his rallies. When the election returns were tallied, it soon became apparent while Tennesseans liked Roy Acuff and loved his music, they had no intention of voting for him. Both Browning and Kefauver won comfortable victories over their Republican opponents. Harry Truman lost Shelby County to the Dixiecrats and the feisty little man from Missouri had a long memory; Boss Crump had placed himself outside of the Democratic Party tent and whatever influence he wielded nationally was gone.

Truman’s victory stunned just about everybody save for Truman himself. It was soon apparent that Senator McKellar was not going to get along well with his new Senate colleague. Even before Estes Kefauver took the oath of office, he was in hot water with his soon to be senior colleague. McKellar wrote a blistering multi-page letter excoriating Kefauver, referring to an incident where Senator McKellar was having lunch at the Mayflower Hotel where he lived while in Washington. McKellar was approached as he dined by a gentleman from Tennessee who promptly disclosed he and Senator-elect Kefauver had agreed on a prospective appointee for a Federal office. McKellar, who carefully guarded his own prerogatives, was astonished and his explosive temper began to boil. Senator McKellar wasted no time in dressing down Kefauver, accusing the Chattanoogan of having a peculiar idea about cooperation. McKellar claimed Kefauver’s idea of cooperation was to do all the operating, while leaving the “co” to McKellar.

Kefauver sent a message to McKellar he wished to come to McKellar’s office and tried to smooth over the disagreement, but Kefauver soon made things much worse. Like many newly elected members of the Senate anxious to control the levels of power, Kefauver complained about the seniority system, which had elevated Kenneth McKellar to the height of influence in the United States Senate. Kefauver had sought assignment to the Senate Appropriations Committee, a committee long headed by McKellar. As a member of the Democratic Senate Steering Committee, McKellar was one of the members who doled out assignments to newly elected members and Kefauver was told two senators from the same state did not serve on the Appropriations Committee together. Kefauver was placed on the Judiciary Committee, which he had also requested.

McKellar was once again Chairman of the Appropriations Committee and wished to again be elected by his colleagues as President Pro Tempore of the Senate. McKellar was challenged by Maryland Senator Millard Tydings, but managed to beat back Tydings to again be the Senate’s President Pro Tempore.

Senator Kefauver was soon complaining to President Truman about patronage in Tennessee. Kefauver reproached the President, expressing his dissatisfaction that virtually all the Federal patronage in Tennessee went to Senator McKellar. Kefauver cited an example of being contacted by the prestigious McCallie School in his home city of Chattanooga; a delegation of boys from the school wanted a brief appointment with Truman and when Kefauver had contacted the White House, he was ignored. Officials at McCallie had the good sense to contact McKellar, who instantly arranged the desired appointment. It was profoundly embarrassing to Kefauver and a small, but clear demonstration of the McKellar clout in official Washington.

Kefauver complained long and loud about his lack of success with patronage in Tennessee, finally thoroughly irritating President Truman who wrote back he had no responsibility to “Straighten out every factional fight in every State of the Union.” Truman’s personal dislike of Senator Kefauver would continue to grow until he reached the point of positively loathing the Tennessean.

Kenneth McKellar had not especially liked Estes Kefauver either; they were from competing wings of the Tennessee Democratic Party and Kefauver had once considered challenging the venerable old senator, a sin for which there was no forgiveness in McKellar’s mind. McKellar had watched Kefauver at the Democratic National Convention in 1944 and noted to Crump that Kefauver had tried to claim Virginia’s Thomas Jefferson as a Tennessee president, telling the Memphis Boss Kefauver was “about as stupid as they make them.” Privately, McKellar referred to Kefauver derisively as “Cowfever.”

Kenneth McKellar soon made a curious announcement, saying he had changed his mind about being “out of politics,” citing “conditions in Tennessee” as the reason why he had decided to keep his options open. It was evident the aging Senator McKellar intended to remain a force to be reckoned with not only in Washington, D. C., but Tennessee as well.