On January 29, 1952, Kenneth McKellar celebrated his eighty-third birthday. He had served as Tennessee’s United States Senator for quite nearly thirty-six years after almost six years spent in the House of Representatives. McKellar was photographed by the Nashville Banner being fed a piece of cake by one of his secretaries as part of his small birthday celebration. Despite obvious signs of age and increasingly poor health, McKellar had announced his intent to seek an unprecedented seventh term in the Senate.

Governor Gordon Browning who had long cherished ambitions of serving in the United States Senate himself had concluded he would run if McKellar chose to retire, died or withdrew from the race. Congressman Albert Gore was already running hard to replace McKellar.

Gore represented a very real threat to the continued tenure of McKellar and it was readily apparent to the Senator’s supporters he would have to return to Tennessee to campaign unlike his effort six years earlier when he had won easily without once coming home.

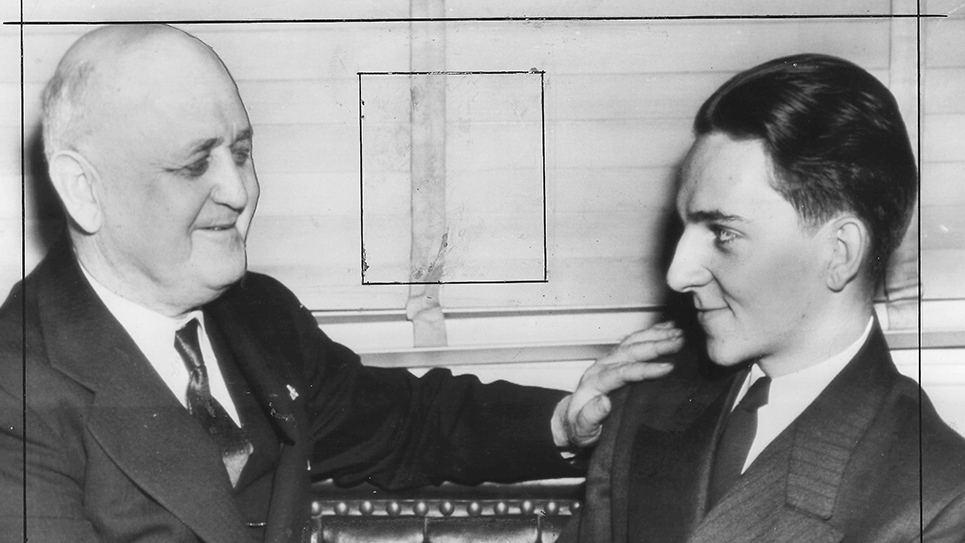

Cookeville was chosen as the site of Senator McKellar’s homecoming to Tennessee. It was not coincidentally the largest city inside Albert Gore’s own Congressional district. McKellar’s appearance was to be an all day affair with music, food and being a political event, speeches. Caravans of automobiles filled with supporters made the journey to Cookeville and estimates of the size of the crowd awaiting McKellar ran as high as ten thousand persons. An elaborate stage had been built for the occasion, with an enormous banner hanging above it urging voters to reelect K. D. McKellar to “preserve Tennessee’s power in the U. S. Senate.” Country music legend Hank Williams entertained the audience and Alvin “Sergeant” York, himself a legendary figure, was on hand to greet his old friend Kenneth McKellar.

Large posters bearing a picture of McKellar from a decade earlier were joyously waved back and forth by supporters, as were signs stating, “Thinking Fellow Votes McKellar” when the old Senator finally got to the podium to speak. McKellar spoke for almost an hour, reassuring his listeners that he was fit to continue serving in the Senate. He said he had worked harder in the last six months than at any other time in his life, presenting the detailed appropriations bills to the Senate. In his typically forthright manner, McKellar acknowledged his own greatest liability – – – his age – – – and more indirectly, his frailty, admitting he suffered from “a little rheumatism in my left leg.”

Senator McKellar reminded his audience of the many projects he had brought to Tennessee over his lengthy Congressional service. McKellar, in spite of his advancing years, pointed to the future, saying he wished to remain in the Senate long enough to see four-lane highways stretching from upper East Tennessee all the way to Memphis. Yet, in the course of his speech, a small incident underlined the old Senator’s disabilities as he reached for a glass of water. McKellar’s hand shook so badly he had to put the glass down without taking so much as a sip in the blistering July heat.

Following the rally, a huge fried chicken dinner was held, which Senator McKellar enjoyed, visiting with old friends and trying hard to make new friends.

The opening of McKellar’s statewide campaign was judged to be a success. A headquarters for the McKellar campaign was opened in Memphis, although McKellar himself was not present. Congressman Clifford Davis stood in for the absent McKellar, praising the Senator’s record and pointing out McKellar had brought almost $4 billion to Tennessee, a mind-boggling sum at the time.

The “Thinking Fellow Votes McKellar” posters began appearing all across Tennessee and the clever little slogan, a subtle reminder to voters of McKellar’s clout in the nation’s Capitol, gave Congressman Albert Gore some momentary concern. Gore himself later admitted the appeal to Tennesseans as to who could do more for Tennessee was a powerful argument. Gore and his wife, Pauline, contemplated a response. Gore credited Pauline with the pithy retort to the McKellar slogan: “Think Some More And Vote for Gore”.

The younger and photogenic Gore, despite a continual need for campaign contributions, used every available medium to reach Tennessee voters. Gore moved about the state at a frenetic pace, shaking hands, playing checkers at country stores, making speeches over the radio and even used the new medium of television. The Congressman, an accomplished fiddle player, even brought out his fiddle for some audiences. Gore boldly invaded Shelby County and Memphis, the domain of E. H. Crump and McKellar’s home base. Despite having urged the Senator to retire, Crump remained loyal to his old friend and the machine was working hard for McKellar.

Gore remained complimentary of McKellar and his long service to Tennessee, but always referred to the Senator in the past tense. Gore was also careful to point out the elderly McKellar would not suffer want should he be defeated, saying the Senator was eligible for a comfortable pension.

Senator McKellar’s own campaign schedule was in marked contrast to that of the youthful Gore. McKellar’s campaign appearances were carefully choreographed and limited to visiting Tennessee’s larger cities. McKellar received voters at local hotels, shaking hands with supporters, causing the ever critical TIME magazine to say the Senator “tried hard to be pleasant to the voters, a real effort for a man as crusty as McKellar.”

McKellar and his entourage traveled comfortably in an air-conditioned bus, making stops in Jackson, Knoxville and Chattanooga.

Senator McKellar returned to Memphis where a special carnival had been planned in his honor. McKellar, joined by Memphis Mayor Watkins Overton, Chairman of the Shelby County Commission E. W. Hale, and his brother, Clint, spoke from the rear platform of a train brightly beribboned for the occasion. The highlight of the evening was the naming of a large man-made lake for the Senator.

As Election Day approached, many believed McKellar had managed to cut into Albert Gore’s lead and make a race out of it. LIFE magazine, another Luce publication unfriendly to McKellar, described the senator as being “chipper and confident”. Senator McKellar himself was convinced he would win, although Crump and Democratic National Committeeman Herbert “Hub” Walters thought otherwise. It was not to be. McKellar’s service in the United States Senate came to an end in the August Democratic primary. McKellar, as always, remained popular in Republican East Tennessee and he carried the First Congressional district, as well as his home district of Shelby County. Congressman Gore carried everything else. Interestingly, McKellar carried Putnam County, the site of his major campaign rally during the senatorial primary.

Admitting he was “surprised” by the outcome of the election, McKellar was gracious in defeat, promptly offering his congratulations and support to the victorious Gore. Surrounded by supporters at a Memphis hotel, McKellar said, “I congratulate my opponent. Yes, I was defeated but I have no hard feelings against any Tennessean.” McKellar, after resting for a few days in Memphis, returned to his Washington office where he started answering the thousands of condolence letters following his defeat. McKellar told friends he was not bothered by his defeat, wistfully telling one correspondent perhaps it was just as well for him in the long run. Senator McKellar did not snipe privately at Gore, but said he “genuinely hoped” Tennesseans would find Gore “better fitted for the place that I would have been.”

McKellar’s long-time political partner E. H. Crump wrote the old senator, lamenting his defeat, but reassured McKellar he would be remembered as Tennessee’s greatest United States Senator.

To the end of his term of office, McKellar routinely performed the numerous favors and services he had provided constituents for the last thirty-six years. Not only was McKellar not at all bitter over his defeat in the senatorial primary, but he actually seemed somewhat more carefree. Senator McKellar was on hand at Washington’s Union Station in late October of 1952 to welcome President Truman back from a campaign swing on behalf of Democratic presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson. McKellar was photographed wearing a baseball cap perched atop his head emblazoned with Stevenson’s name. The old Senator was standing beside a pretty woman as he signed a scroll commending the Truman Administration.

Unlike many former Congressmen and senators, McKellar had no intention of remaining in Washington, D. C. and trying to relive past glories of a time gone by. McKellar preferred to go home to Memphis where he had family members. McKellar’s term ended on January 3, 1953 and the former Senator lingered in Washington for a few months, tending to the details of closing out his Congressional service and making the necessary arrangements to have his papers and memorabilia shipped to Memphis. McKellar threw little away and his collection filled several train boxcars as they were shipped back to Memphis.

Having never married, McKellar returned to his apartment in the Gayoso Hotel, once a proud hostelry that was then in decline, despite its claim as the “South’s Most Aristocratic Hotel.”

McKellar tried to keep up with current affairs and still corresponded with old friends and colleagues sporadically. McKellar was asked if he missed serving in the Senate, to which he replied he did not, although he did say there was nothing quite like the Senate. It is difficult to believe McKellar did not miss the United States Senate where he had spent the bulk of his adult life.

Many of McKellar’s siblings were gone, although the former senator was invited to dinner by nephews and nieces, many of which had growing families of their own. McKellar was asked if he would run for the Senate in 1954 against Estes Kefauver, hardly a realistic prospect as McKellar was almost eighty-five years old and in declining health. McKellar entertained no illusions and quickly replied his political career was over. McKellar still retained his personal dislike of Estes Kefauver and supported Congressman Pat Sutton in the Democratic primary.

McKellar’s friend and political ally, E. H. Crump, master of Memphis, died in October of 1954 and the former Senator attended the services for his old friend and was genuinely sorry and terribly grief stricken by Crump’s passing.

McKellar’s last foray into politics was being named as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1956, but the frail former senator was too ill to attend. McKellar finally admitted his doctors strongly advised against his going, even though a plane was put at his disposal. McKellar told one correspondent his legs gave him so much trouble he was largely confined to his hotel suite.

Senator McKellar, having already penned a book about Tennessee’s United States Senators, tried to keep himself busy by writing a memoir of his own Congressional service and the seven Presidents he had served with over the years. McKellar managed to dictate several hundred pages of material, but the book was never finished.

McKellar underwent a serious operation for an ulcer in 1957 and his nephew Judson advised an inquiring admirer that his uncle still had an iron constitution and seemed to be making a good recovery and had a good appetite. McKellar survived the surgery, but his health was failing fast and he died from kidney failure on October 25, 1957.

The legacy of Kenneth McKellar’s senatorial career still stands in the form of those projects he promoted and protected as Tennessee’s United States Senator. Oddly, no building in Tennessee is named for McKellar despite the fact he brought more in the way of federal projects than any of his predecessors or successors. The Tri-Cities Airport was once known as McKellar Field and the airport in Jackson, Tennessee was named for the Senator. The old K. D. McKellar Elementary School in Milan is no more.

There is a statue of McKellar at the Tri-Cities Airport and while there are few monuments to Kenneth McKellar, it can truly be said he lived his life in service to the people of Tennessee. There can be no greater monument to any man.