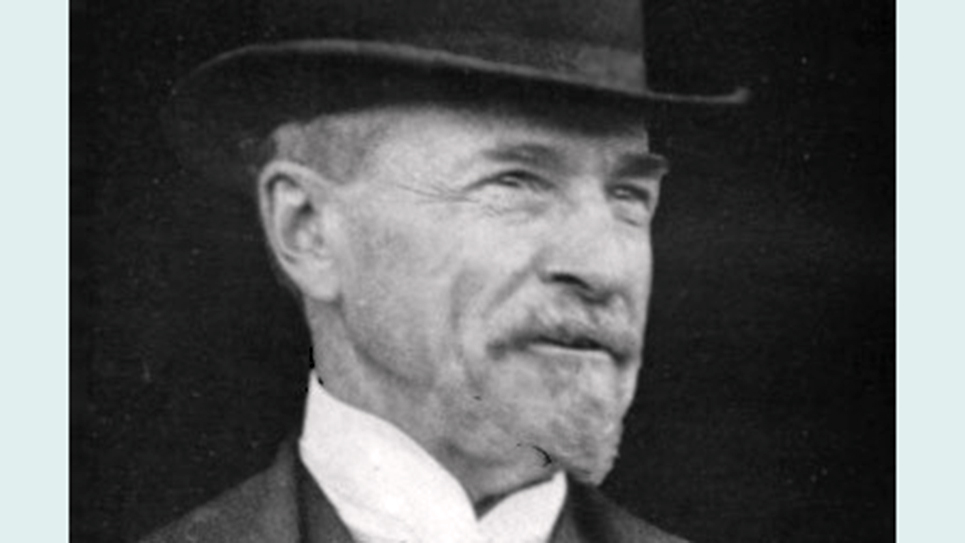

Henry Clay Evans had been elected to Congress from Tennessee’s Third Congressional District in 1888 as a Republican. His victory had been a profound shock to local Democrats who promptly gerrymandered his district and castigated the congressman for his support of the Lodge Bill, which was intended to preserve the voting rights of Black citizens.

In 1894, H. Clay Evans was nominated by Tennessee Republicans to face Governor Peter Turney in the gubernatorial race. A ponderous, heavyset man with a receding hairline and a beard, Turney had been Chief Justice of the Tennessee State Supreme Court and sixty-seven years old at the time. Turney’s most notable achievement may well have been siring twelve children between his first and second wives.

At the time, Tennessee’s Republican Party was strong in East Tennessee, which corresponded with where the old Whig Party had been strong and where the prevailing opinion favored the Unionist cause over that of the secessionists. Following Reconstruction, Democrats had come back to power in 1870. Republicans were a distinct minority in the Volunteer State and only seemed to be able to win a statewide election when the Democrats were seriously divided. That had happened in 1880 when Republican Alvin Hawkins had been elected. Incumbent Albert Smith Marks had served one two-year term and the state was struggling with a serious debt problem that had plagued the state government. Governor Marks chose not to seek reelection in 1880 because the Democratic Party in Tennessee was deeply divided over how to resolve the debt problem. That division helped Alvin Hawkins to win a two-year term as governor of Tennessee.

Throughout much of 1893, many newspapers across Tennessee, irrespective of party affiliation, speculated that Governor Turney would have a serious opponent if he chose to run for the Democratic nomination once again in 1894. Newspapers regularly reported instances of once prominent Turney supporters who had soured on the governor. Much of that discontent came from those naturally disappointed by the governor’s distribution of the patronage at his disposal and other appointments. Those carping about such appointments were soon labeled the “Malcontents” in the state’s press. One of the leading malcontents in Tennessee was the editor of the Nashville American.

Governor Turney likely did himself some considerable harm when he engaged in a public spat with State Comptroller James A. Harris over how best to fund a new penitentiary. Democrats were also alarmed when their judicial ticket only narrowly beat a field of candidates backed by a combination of Republicans and Populists. Turney managed to be renominated without any real trouble.

Tennessee Republicans had a division of their own; two factions, one headed by H. Clay Evans and the other by Congressman John C. Houk of Knoxville, contended to nominate the GOP candidate for governor. Houk had succeeded his father, Leonidas, in Congress and bitterly resented the fact Evans, a strong supporter of the administration of President Benjamin Harrison, controlled federal patronage in Tennessee.

The Evans men rallied behind the candidacy of Colonel David A. Nunn, who had been elected as a Republican to Congress for a couple of terms from Memphis. Nunn had also been Tennessee’s Secretary of State from 1881-1885. During the state Republican convention, it became all too clear David Nunn had no intention of accepting the gubernatorial nomination. There is some reason to believe the candidacy of Colonel Nunn was little more than a diversion while the potential gubernatorial candidacy of H. Clay Evans was quietly being organized and promoted. Much of the Evans campaign for the GOP nomination was organized by Chattanooga industrialist Newell Sanders, a close personal friend of H. Clay Evans. Sanders would remain one of Tennessee’s most prominent and influential Republicans and was appointed to serve briefly in the United States Senate following the death of Senator Robert Love Taylor. Timing is an essential ingredient for success in politics and the Evans organization timed events perfectly. At the appropriate moment, Colonel David Nunn stood up and declared he was too old to run for governor and that Republicans needed a young and vigorous candidate who could carry the campaign to every corner of the state.

Clay Evans inherited much of Nunn’s support in West and Middle Tennessee as well as having a strong base in his own East Tennessee. Jack Baker was the candidate of Congressman John Houk yet Houk’s leadership was fiercely contested by Judge Henry Gibson of Knox County. Judge Gibson controlled a number of the fifty delegates from Knox County, which weakened Baker’s candidacy. Another significant difference between the two gubernatorial campaigns was Evans welcoming support from Black Republicans. In contrast, the Houk faction was considered to be “cool, if not hostile” to Black Republicans. Baker’s candidacy was further hampered by the fact a majority of the Davidson County delegation to the Republican state convention favored H. Clay Evans rather than native son Jack Baker.

The standing of H. Clay Evans was such that many of Tennessee’s most Democratic newspapers lambasted his record while in Congress, but never attacked him personally nor assaulted his character. Most of the criticism of H. Clay Evans was centered around his support for the Lodge Bill, which was denounced by former Confederates and Democrats as the “Force Bill.” Those newspapers devoted to the Democratic Party warned their readers that while Evans likely had no chance of being elected governor, he should not be taken lightly. “Mr. Evans is a shrewd, skilled politician and can bring to bear the strongest influences of his party in his canvass,” the McMinnville Southern Standard cautioned.

Evans opened his campaign for governor in Huntingdon, Tennessee, a west Tennessee community in Carroll County, which was also the home of former governor Alvin Hawkins. The wealthy H. Clay Evans had little difficulty in financing his gubernatorial bid, which proved to be another source of vexation by the Democrats. Evans’ campaign was also superbly well managed by his friend Newell Sanders. Election night proved to be a harrowing experience for Governor Peter Turney and Tennessee Democrats. As each of Tennessee’s counties reported its vote, it became absolutely certain H. Clay Evans had been elected governor of Tennessee. Returns clearly demonstrated Republicans had made gains in virtually every county in the Volunteer State. Almost immediately Democrats began insisting the Republicans had won by voter fraud, especially in GOP-dominated East Tennessee. Secretary of State William S. Morgan refused to announce the official returns, insisting the sheriff of each county provide a copy of the poll registration books showing the ballots cast. When Morgan finally did release the official vote tally, it showed H. Clay Evans had defeated Peter Turney by 748 votes.

When the legislature met in January of 1895, which was overwhelmingly populated by Democrats, the first order of business was to reelect Isham G. Harris to the United States Senate. A former governor and Confederate general during the Civil War, Harris was the leader of the “bourbon” faction of Tennessee Democrats, of which Peter Turney was a member. The legislature then began an “investigation” of charges of voter fraud made by Democrats surrounding the election of H. Clay Evans. The Tennessee General Assembly allowed Peter Turney to remain in office as governor while they conducted their own investigation.

Eventually, the legislature threw out several thousand ballots cast for H. Clay Evans. The final vote tally accepted by the Tennessee General Assembly was 94,260 for Peter Turney and 92,266 for H. Clay Evans, a difference of 2,354, which gave the election to the incumbent.

Peter Turney’s reputation never recovered from the decision and it further split Tennessee’s Democratic Party. H. Clay Evans became a martyr and gained a national reputation in the wake of the actions of the Tennessee General Assembly. Evans was the runner-up to winner Garrett Hobart for the GOP vice presidential nomination in 1896. Hobart had 533 votes to 280 for Evans. Still, President William McKinley found a place for Evans in his administration, appointing the Tennessean Commissioner of Pensions. At a time before there was Social Security and no pensions from the federal government, it was an important and sensitive position. Evans made headlines when he published a list of 3,568 veterans who were receiving a pension of $45 per month (the equivalent of almost $1,600 today), which was only supposed to be received by those adjudged to be completely disabled. The list published by Commissioner Evans proved to be quite embarrassing as it continued the names of some very prominent and successful men who were not totally disabled.

That caused a reaction on the part of the organization of the Grand Army of the Republic to petition for the removal of Evans as Commissioner of Pensions. Evans was named Consul-General to London in 1902 by President Theodore Roosevelt and he served until 1905 in that post. Evans was later acknowledged to be one of the best administrators ever to serve as the federal Commissioner of Pensions.

Evans was a candidate for governor of Tennessee once again in 1906 and won the GOP nomination over the determined opposition of his nemesis Congressman Walter P. Brownlow of the First Congressional District. G. Edmund Hatcher writing for the Chattanooga News made the pithy observation following a tumultuous Republican state convention, “But there is not a great deal of difference between a funeral and a wedding. In either case, you start somewhere and you never know where you will get off.” The fight between H. Clay Evans and Walter P. Brownlow was for control of Tennessee’s Republican Party more than it was about the gubernatorial nomination. Evans emerged victorious. Brownlow, Hatcher opined, was a “fine fellow” but acknowledged he was certainly not a “statesman” but rather a politician who openly pursued a “rule or ruin” policy in his political dealings.

The Democrats nominated Congressman Malcolm Rice Patterson of Memphis to be their gubernatorial nominee. Patterson had bested incumbent John I. Cox of East Tennessee for the Democratic nomination. Cox had succeeded to the governorship when James Beriah Frazier had resigned, having been elected to the United States Senate. The results of the election were not surprising as Tennessee was a solidly Democratic state and the party was not irrevocably spilt. Patterson won the election, but his time as governor would deal Tennessee’s Democratic Party a bitter blow, tearing the organization asunder and enabling bolting Democrats and Republicans to join together to create the “Fusion” movement. The “Independent” Democrats and Republicans would elect a GOP governor for two terms and both United States senators from the Volunteer State. Malcolm Rice Patterson would become one of the most polarizing figures in Tennessee politics. Patterson fought one of the most bitter races in the state’s history when he defeated former U. S. senator Edward Ward Carmack in the 1908 primary. Carmack, a highly popular figure, ran as the champion of the “dry” or prohibition forces in Tennessee, while Governor Patterson was openly “wet.” Patterson’s pardon of Carmack’s killer turned Tennessee’s politics upside down.

H. Clay Evans returned home to Chattanooga where voters adopted the “commission” form of government. Evans was promptly elected to serve as Chattanooga’s Commissioner of Health & Education. It was H. Clay Evans who organized Chattanooga’s first modern public school system. Evans also served as a trustee of both the University of Tennessee and the University of Chattanooga (later UTC).

Sunday, December 11 was an ordinary and pleasant day for the seventy-eight-year-old semi-retired statesman. Evans and his wife had taken a long automobile ride and returned home where they had guests for dinner. There was not a shred of evidence to suggest Evans was remotely ailing.

H. Clay Evans went to bed on the night of December 11, 1921, and was believed to be in the best of health, especially for a man of his years. Sometime during the night, the heart of H. Clay Evans stopped beating and he slipped away. His son-in-law Dr. John W. Johnson found Evans lying in his bed, a smile still on his face. H. Clay Evans had died a happy man.