The 1956 Presidential Election in Tennessee II

By Ray Hill

Democrats all across the South had gathered in Knoxville, Tennessee, to plan the strategy for the fall campaign at the end of August in 1956. At least ten states had been represented, including much of the Democratic Party’s leadership. An editorial appearing in the Chattanooga Daily Times lauded the Democratic gathering and the resulting unity. Even then Democrats hated Republicans referring to the “Democrat Party” rather than the “Democratic Party.” The Chattanooga Daily Times actually printed another editorial on the subject of “To ‘IC’ Or Not To “IC’.” The editorial noted Carroll Reece had tormented Democrats by repeatedly and purposely using “Democrat Party” while he was chairman of the Republican National Committee in 1946. The Daily Times sullenly huffed Reece was “the longtime embodiment of Tennessee failure in the Republican party.”

Yet things were changing in the Volunteer State. The 1952 presidential race in Tennessee saw the movement of white middle-class voters in the suburbs to vote for at least some Republican candidates. Since the turn of the century, Republicans had won only three presidential contests in Tennessee and an equal number of gubernatorial contests. Tennessee had never popularly elected a Republican to the United States Senate. There had been two serious tries by Republicans to win a Senate seat; the first was the 1916 race when former governor Ben W. Hooper contested with then-Congressman Kenneth D. McKellar to become the first person ever popularly elected to the United States Senate. The second truly serious effort made by a Republican to win a seat in the U.S. Senate had been Carroll Reece’s race in 1948; the former congressman had run with country music entertainer Roy Acuff as his running mate for governor. Republicans had thought there was a good chance GOP presidential nominee Thomas E. Dewey might carry the Volunteer State, especially as E.H. Crump and his Shelby County machine had bolted the party, refusing to support Harry Truman. President Truman won just under 50% of the ballots cast, with Tom Dewey winning only approximately 37% and States’ Rights candidate Strom Thurmond winning around 14%. Still, Republican division in the state showed itself with the election returns for the Reece-Acuff ticket. Some 202,914 Tennesseans cast their votes for Dewey while Carroll Reece tallied 166,947 votes. Estes Kefauver won more votes in running for the United States Senate than were cast for Harry Truman; Kefauver had 326,142 votes while Harry Truman got 270,402 ballots.

Guy Lincoln Smith was chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party as well as the editor of the Knoxville Journal, which was the voice of East Tennessee Republicanism. Much of the failure to support the GOP ticket came from the Second Congressional District and Smith was deeply unhappy when the election returns showed Reece and Acuff had lost Knox County to their Democratic opponents by about 5,000 votes or more. Yet Thomas E. Dewey carried Knox County over Harry Truman by 5,000 votes. Smith pushed Carroll Reece to reclaim his seat in Congress while at the same time the Journal backed the candidacy of Howard Baker (father of the future senator) against Second District Congressman John Jennings Jr. Both Dayton E. Phillips, who had taken Reece’s seat in the House, and Jennings lost in the Republican primary.

Tennessee had narrowly favored Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1952 election and some Democrats theorized that the failure of Estes Kefauver’s campaign for the nomination of his party had caused some not to vote for Adlai Stevenson that year. Democrats confidently expected to return Tennessee to the Democratic column in the 1956 election as Kefauver had shown his own strength when Adlai Stevenson had thrown open the vice presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention. The delegates had chosen the vice presidential nominee and Kefauver had overcome all challengers, including two from his home state: Frank Clement and Albert Gore. In the end, it was a race between Estes Kefauver, whom Lyndon Johnson (who also lost the vice presidential nod) had called “the greatest campaigner of them all”, and a young United States senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy. A poor public speaker, Estes Kefauver had probably shaken more hands during his political career than any other candidate. Kefauver demonstrated a remarkable ability to connect with voters while campaigning from hand to hand. With Kefauver on the Democratic ticket, the Volunteer State should return to the party of Andrew Jackson. Republicans had carried Tennessee in 1920 and 1928, but those elections had been political aberrations, Democrats argued. There had been no political realignment of voters and voting patterns. Gains made by Republicans had been quickly reversed.

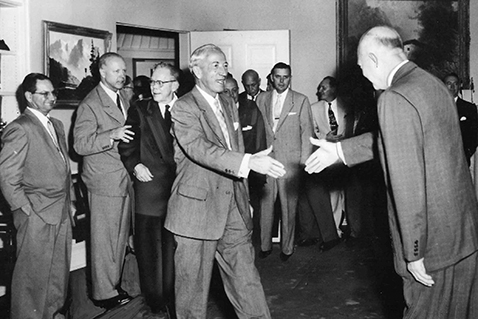

The 1956 election saw Tennessee become yet again a battleground state between the Republican and Democratic parties. Both political parties felt they had a good chance of carrying the Volunteer State. Guy L. Smith certainly believed President Eisenhower could carry Tennessee in the general election. Once again, the editor was the campaign manager for the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket in Tennessee. In mid-September, Congressman Carroll Reece, Tennessee’s Republican National Committeeman since 1939 and a former chair of the Republican National Committee, boarded a train to attend a conference with the president at Eisenhower’s home in Gettysburg. Eisenhower was hosting prominent Republican leaders to map out the fall campaign.

Reece stepped over the border of his congressional district to campaign for William C. Wampler, a young Republican who had won a seat in Congress in 1952. Young Wampler was the son-in-law of Congressman Howard Baker (and brother-in-law to future Senator Howard Baker, Jr.) who was seeking a comeback in the 1956 election. Congressman Reece then traveled to Nashville to greet Vice President Richard Nixon who came to campaign in Tennessee. As James Stahlman, publisher of the Nashville Banner, was introducing Richard Nixon in the capital city, his newspaper was running stories about the collection of campaign funds from state employees. The campaign funds were being collected by Everett LaFon, Director of the State Safety Department’s drivers’ license bureau who denied any pressure had been applied to employees. Joe C. Carr, Tennessee’s longtime Secretary of State, said employees were “given the opportunity to contribute, as is customary in election years.”

The organization of Carroll Reece was an important factor in turning out the vote in the heavily Republican First Congressional District. Indeed, the Reece organization was the Republican organization in the First District. Robert Clark of Blountville had been campaign manager for Congressman Carroll Reece in the 1950, 1952 and 1954 elections in Sullivan County; Clark became one of the managers for the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket in 1956.

Congressman Reece habitually moved through his district and in Jonesboro, he told a gathering of Republicans, “The Republican administration has restored fiscal integrity to the government with efficiency and economy in place of Democrat waste and extravagance.”

As Election Day approached, Carroll Reece welcomed former Republican presidential standard-bearer Thomas E. Dewey to the First District. Natty in a double-breasted suit, the former New York governor had an overcoat casually draped over his arm as he arrived in Johnson City. The congressman and former governor were greeted and escorted by young Thomas Carr, who was named for Dewey.

In his speech Dewey taunted Estes Kefauver, saying the farm supposedly owned by the senator existed only in “somebody’s fertile imagination like some of the issues the Democrats have been raising.” “So far as I can find out,” Dewey said, “the senator isn’t even sharecropping anything.” Pointing to the votes cast by the Tennessee delegation at the Democratic Nation Convention which had been hostile to Kefauver, Dewey chortled, “Certainly the Democrats know him because it took his state so long to give him a vote. Your Governor can tell you all you want to know.” Dewey knew how to campaign even if he didn’t do much of it in 1948; the former New York governor told his audience Adlai Stevenson was unworthy of “wearing the mantle” of Tennessee Democrats like Andrew Jackson and Cordell Hull.

Evidently, every seat in the East Tennessee State College auditorium was filled, bringing the audience to something like 5,000 people or more. Dewey and Carroll Reece had a history and were from different factions of the Republican Party, but both were old pols and political professionals. Both were highly cordial and the congressman was beaming. Tom Dewey’s speech was nicely summarized by one reporter as a “praise-Ike-give-Adlai-hell” talk.

Carroll Reece remained on the campaign trail and told a Republican rally at the Unaka School, “No man in the nation is better qualified to lead the defense of the United States, should the need arise, than President Eisenhower.”

As Election Day approached, Republicans were hopeful while Democrats in Tennessee were confident with native son Estes Kefauver on the presidential ticket. That confidence was shattered as the election returns began to come in and be counted. Eisenhower remained popular in the Volunteer State. Adlai Stevenson won 29,768 votes in Knox County, but the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket polled 46,167 and about 65% of the ballots cast. Stevenson fared better in the Democratic stronghold of Davidson County (Nashville), in which the former Illinois governor won 56,822 votes as compared to 37,077 for Eisenhower. Yet it was astonishing to many Democrats that a Republican could pull almost 40% of the vote in Davidson County. More astonishing to Democrats was the fact Dwight D. Eisenhower carried the former domain of Edward Hull Crump, Shelby County. The Memphis Boss had died in 1954 but had managed to carry Shelby County for the Democratic ticket in 1952. With Crump gone, many conservative Democrats opted to vote for the Republican ticket. Eisenhower won Shelby County 65,690 to Stevenson’s 62,051. Likewise, the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket carried Hamilton County (Chattanooga). The margins won by the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket in Republican East Tennessee was greater than those won by the Stevenson-Kefauver ticket in the rest of the state. The loss of Memphis and Shelby County helped to tip the balance; Eisenhower carried the Volunteer State by the narrow margin of 5,781 votes.

The Nashville Tennessean published the election returns by congressional district, which illustrated the lopsided margins given President Eisenhower by voters in East Tennessee. The Eisenhower-Nixon ticket won 87,645 votes in Carroll Reece’s First District while Adlai Stevenson polled 36,587. Eisenhower tallied 91,852 votes in Tennessee’s Second Congressional District with Stevenson well behind with 55,281 votes. Eisenhower also carried the Third Congressional District while Adlai Stevenson won the heavily Democratic Fourth District. Stevenson also carried the Sixth Congressional District, but Eisenhower’s personal popularity was demonstrated by the fact the vote inside Tennessee’s Seventh Congressional District in West Tennessee was almost a draw, the vote totals being separated by less than 2,000 votes. Stevenson carried the Eighth District while Eisenhower won the Ninth District.

There were no other statewide races on the ballot in Tennessee that year; voters had approved changes to the state Constitution giving the governor a four-year term, which Frank Clement had won in 1954. Neither of Tennessee’s seats in the United States Senate was up for election, nor did the Republicans win any additional seats in the Congress in Tennessee that year. The two GOP congressmen, Carroll Reece and Howard Baker (father of the future U.S. senator) won overwhelmingly in their own districts.

The Republicans would fare even better in 1960 and seeds had been planted in fertile ground for the future. Bill Brock, a young businessman, would claim the Third Congressional District for the Republicans in 1962 and Howard Baker Jr. would win a seat in the United States Senate in 1966. Bill Jenkins would become the first Republican to serve as Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1969 while Richard Nixon carried the Volunteer State in the 1968 election. Brock would win Albert Gore’s seat in the Senate in 1970 while Winfield Dunn became the first Republican to occupy the governor’s office in fifty years. By 1972, Republicans would win five of Tennessee’s nine seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. The tide began turning with Dwight Eisenhower.