There was a time when people engaged in voting a straight ticket, meaning they voted for every candidate of one political party or the other. There have also been election cycles where a tidal wave of support empowered one party or the other. 1920 was such a year for the Republicans and 1936 was the same kind of year for the Democrats. Warren G. Harding rode that wave into the White House in 1920, while Franklin D. Roosevelt carried every state in the nation in 1936 but two, Vermont and Maine. One result of those straight-ticket voting habits was the men and women were elected to office that likely would not have been elected under other circumstances. Some began long careers by being elected in a good year for their party and deftly utilizing the tools of incumbency to become entrenched in office.

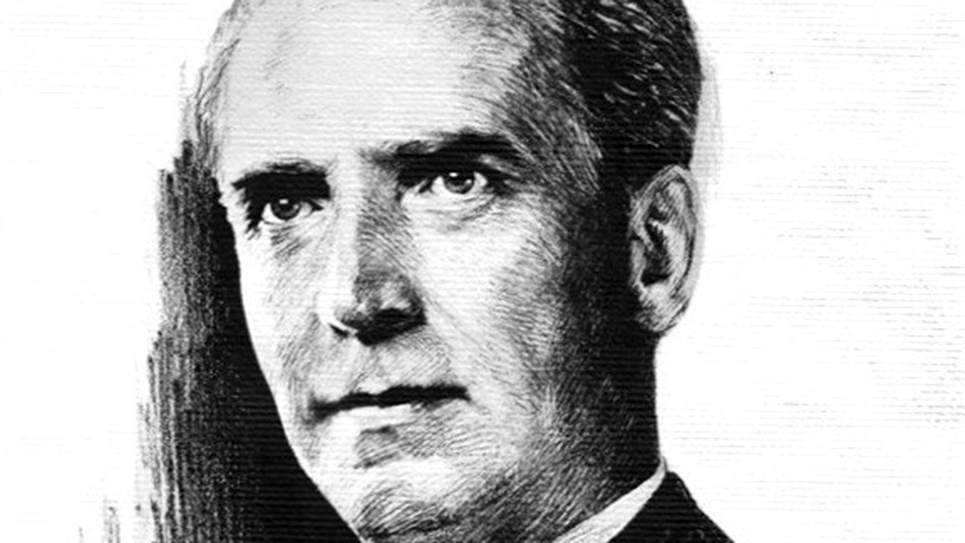

William H. Smathers never succeeded in entrenching himself in office, which was a more difficult feat in a state like New Jersey. Tall and lanky, and well-dressed, Smathers was twice married and the father of eight children. Smathers’ second marriage, to a woman twenty years his junior, likely did him some political harm. Smathers had five children with his first wife and added three more with his second wife. When his first child with his second wife was born, Smathers said, “I feel as if I were just starting life over again.”

Clearly not very diplomatic, William Smathers spoke with a distinct Southern drawl, which is not at all what one expected to hear come out of the mouth of a United States senator from New Jersey. Smathers was also the uncle of three-term U.S. Senator George A. Smathers of Florida. A dog fancier, Smathers was known for raising champion English setters. Like any Southern squire, William Smathers was a devoted fisherman and hunter.

Smathers was a loyal Democrat and in New Jersey, it meant adherence, or at the very least, close cooperation with the big city machine of Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague. Smathers delayed taking the oath of office as United States senator for thirteen weeks to assist Hague. When he was first elected to the U.S. Senate, William H. Smathers was a member of the New Jersey state Senate. Following the 1936 election, the Republicans controlled that body by only a single vote while one seat was being disputed between the two political parties.

When William Smathers finally arrived in Washington, D.C. he was decked out in a morning coat (a cutaway with tails), shirt with a bat-wing collar, and took the oath as his five children peered down from the Senate Gallery.

As is usual with a new member of the United States Senate, newsmen pondered just how that senator would vote on the issues facing Congress. Smathers was not at all reticent about speaking to the press and reporters quickly noted some of his utterances were at variance with one another. “I personally believe, it is time for the New Deal to taper off a bit,” Smathers had intoned. Yet Smathers also said, “Understand I am for President Roosevelt and his policies, absolutely.” If that confused veteran observers of Capitol Hill, William Smathers made it even more bewildering. “My ideal of a U.S. Senator is Carter Glass of Virginia,” Smathers stated. Carter Glass, a veteran member of Congress who had also served as Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of the Treasury was a deeply conservative senator whom FDR laughingly referred to as “an unreconstructed rebel.” Smathers added, “All of the people of the nation will be best served by adding new and youngers members to the Supreme Court,” as Roosevelt kicked off his bid to pack the highest court in the country. Smathers’ statement was diametrically opposed to the position taken by New Jersey’s other United States senator, A. Harry Moore, who was also a Democrat.

One political reporter for TIME magazine chortled, “New Jersey is ready to go whichever way the political cat jumps.”

A beneficiary of a wave election, William Howell Smathers was not a native of New Jersey, having been born in North Carolina. Indeed, Smathers was about as Southern as could be at the time, the scion of a well-to-do family and had actually been born in what would have been known as a plantation home. It was only after graduating from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, that William Smathers moved to the Garden State. Smathers was barely thirty-one years old when he first became a judge of the common pleas court in Atlantic City. That was the political domain of Enoch “Nucky” Johnson as depicted in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. Johnson was a Republican while Smathers was a Democrat.

William Smathers was at least always on the periphery of politics in his adopted state, if not directly involved. While serving as a judge, Smathers was considered to be tough in dispensing justice to those who appeared before him. Judge Smathers was especially hard in his judicial pronouncements and sentencing of racketeers, of which there was a large number in New Jersey. Not surprisingly, Judge Smathers was the frequent recipient of death threats. The judge habitually carried a loaded pistol. After serving as an assistant state attorney general, Smathers won an ordinarily strongly Republican seat in the state Senate from Atlantic County. William H. Smathers was the first Democrat to hold that particular seat in the New Jersey state Senate in sixty years. Naturally, political bosses, at least those with good instincts, look for candidates who have demonstrated the ability to garner votes and have proven to be popular, especially in those areas where their party is weak. Frank Hague selected Smathers to challenge incumbent Senator Warren Barbour.

Barbour, a Republican, was a wealthy businessman who had at one time been the amateur boxing champion of the United States. Warren Barbour had been appointed to the United States Senate in 1931 following the death of Senator Dwight Morrow, the father-in-law of famed aviator Charles Lindberg. A year later, Barbour had to face the people of New Jersey in a special election to serve out the remainder of the late Dwight Morrow’s term of office. Barbour only narrowly won and had the misfortune of running again in yet another great year for Democratic candidates in 1936. Smathers won a decisive victory over Senator Barbour. Warren Barbour would return to the United States Senate and serve alongside Smathers when A. Harry Moore resigned in 1938.

William Smathers was one of the younger members of the United States Senate, only forty-five years old at the time of his election. As a member of the Senate, Smathers tried to ease the plight of European refugees in 1939 when he sponsored legislation to assist those seeking religious and political freedom. Senator Smathers also tried to incorporate Cuba as a state in the United States, an idea that pleased no one, including the Cubans who pointedly said they weren’t interested.

Senator Smathers caused something of a stir when the Senate was considering the Lend-Lease Bill and the New Jersey solon commented the delay in approving the legislation quite nearly proved Adolf Hitler was right inasmuch as “a little band of evil men could gang up to defeat democracy.” The fight over the Lend-Lease Bill was fought between the powerful isolationist bloc in Congress, which was profoundly opposed to American participation in another foreign war and the internationalists who believed the United States faced peril by simply sitting off by itself. A group of women who styled themselves as the “Mothers’ Crusade Against Bill 1776,” lobbied hard against the Lend-Lease Bill. Mrs. Elizabeth Jane Dilling, the leader of the Mothers’ Crusade, lobbed an insult against Senator Smathers’ senatorial idol, the peppery Carter Glass of Virginia, who favored declaring war immediately. Mrs. Dilling snapped that Glass, who was the father of four children, was “an overage destroyer of American youth.” Mrs. Dilling had tangled with the wrong U.S. senator. Noted for his diminutive size and fighting spirit, which invited frequent comparisons to a bantam rooster, Glass retorted the mothers should be investigated by federal authorities. “It would be pertinent to inquire whether they are mothers. For the sake of the race, I devoutly hope not.”

Senator William Smathers ran for reelection in 1942, which turned out to be a bad year for Democrats in general and Smathers in particular. Perhaps no senatorial race in the nation offered voters a more clear-cut choice between the candidates than that of William H. Smathers versus Albert W. Hawkes. Hawkes was a very wealthy business executive and former president of the National Chamber of Commerce who was as deeply opposed to the New Deal as Smathers was supportive of it. Nor did A. W. Hawkes attempt to sidestep or soft-peddle his political views; Hawkes was an outspoken conservative while Smathers was a loud liberal.

Newspapers in New Jersey offered their assessments of the two candidates. The Plainfield Courier News dismissed Senator Smathers as having “a mediocre record of fence-straddling on national issues.” In contrast, the Courier News believed Albert Hawkes was a man of “intellectual honesty, unselfish purpose, courage” who possessed a genuine “understanding of the needs of the American people.”

The Senate race in New Jersey was not an especially civil affair in 1942; both candidates lambasted the other. Senator Smathers denounced Hawkes as a “lobbyist for the industrial interests” as well as a “Roosevelt hater.” Smathers tossed a variety of epithets at Hawkes, at various times referring to the Republican as a “prohibitionist,” “isolationist,” “labor baiter,” and “economic imperialist.”

“Are the people of New Jersey willing to entrust the writing of the next peace to a man whose primary interest is in the profits of international big business?” Smathers asked.

Hawkes gave as good as he got. The GOP challenger pointed to what he thought Senator Smathers’ “adolescent pronouncements on foreign policy to the embarrassment of the administration.” Albert Hawkes ticked off several examples and reminded voters Secretary of State Cordell Hull had once pointedly noted the foreign policy of the United States was still conducted through the State Department and not the boardwalks of Atlantic City. Hawkes sighed about Smathers having tried to make Cuba the forty-ninth state without bothering to consult the Cuban people about the matter. Hawkes summed up Smathers’ time in the U.S. Senate as a “cumulative record of delinquencies” as he had been recorded as having missed 41% of roll calls in six years.

For once, William Smathers did not defy the odds and lost to Albert W. Hawkes. When the former senator was considered for a new federal judgeship, Hawkes served notice he would fight any effort to nominate Smathers.

Six years after Smathers’ defeat, the bitterness between the two men had not improved. As Hawkes was attempting to be renominated, Smathers fired off a letter he made public demanding the senator “come out and tell the truth of exactly how much you paid for your nomination and election.” Senator Hawkes promptly retorted he had received no communication of any kind from his predecessor. Hawkes sniffed he was looking for the support of those who were “looking forward, not backward six years.”

Smathers had hoped to make a triumphant return to the United States Senate by reclaiming his seat in the 1948 election. The Democratic nomination was dictated less by popular will than the whim of party bosses who feared the former senator would not be the strongest candidate they could nominate. The party bosses gave the senatorial nomination to another, who lost to the GOP candidate in the general election. William Smathers was never again a candidate for public office.

William Smathers continued practicing law until he retired and moved back to North Carolina. When the end came, Smathers was in a hospital in Asheville. Only sixty-four years old, William Smathers passed away having suffered a cerebral hemorrhage.