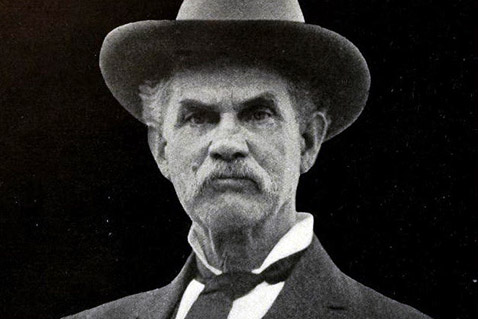

John Sharp Williams of Mississippi

At a time when folks have little or no respect for their officeholders, it may be difficult to imagine the better part of the people of an entire state having affection and reverence for their representative in Congress. Yet that was true of the people of Mississippi and John Sharp Williams. Williams spent twenty-eight years representing Mississippians in the House of Representatives and the United States Senate. A man of formidable education and possessed of piercing wit, one Mississippian once read a statement made by the Senator and heard his wife say John Sharp Williams should be kept in the Senate by the people of the Magnolia State until he was physically unable to get to the Capitol. John Sharp Williams was certainly quotable and even he realized the nature of the Congress. “I may have grown cynical from long service,” Williams once said, “but this is a tendency I do not like, and I sometimes think I’d rather be a dog and bay at the moon than stay in the Senate another six years and listen to it.”

A Democrat, John Sharp Williams was a devoted supporter of President Woodrow Wilson. Still, as he reflected upon his congressional service, Williams said, “My reading of history convinces me that most bad government has grown out of too much government.”

Williams attended the Kentucky Military Institute, the University of the South, and the University of Virginia. Contrary even as a young man, John Sharp Williams did not receive a degree from the University of Virginia as he refused to take any classes other than those in the liberal arts, although he was still a Phi Beta Kappa student. Williams went abroad where he attended the University of Heidelberg in Germany and the College of France at Dijon. Upon his return to the United States, John Sharp Williams enrolled at the University of Virginia’s law school. Williams was admitted to the Bar in 1877 and married Elizabeth Dial Webb of Alabama that same year.

John Sharp Williams inherited the family plantation, Cedar Grove, in Benton, Mississippi in Yazoo County. Williams returned home and commenced the practice of law and grew cotton at Cedar Grove, which eventually comprised some 8,000 acres of land. At age thirty-nine, John Sharp Williams was elected to Congress from Mississippi’s Fifth Congressional District. Congressman Williams became well known for his impressive debating skills and was an expert in the rough and tumble of extemporaneous speaking. Nor was Williams a political dilettante; he demonstrated his political abilities when redistricting placed him in the same congressional district as two other incumbents and emerged the winner of the Democratic primary. John Sharp Williams rose to become Minority Leader of the House and was nationally recognized for his legislative abilities and prowess. John Sharp Williams’ sense of humor was readily apparent in his congressional service. When the British Navy launched the mighty HMS Dreadnaught, Congressman Williams introduced a bill to rename the USS Michigan the USS Skeered O’ Nothing.

John Sharp Williams announced he would not seek reelection to the House, but rather would run for the United States Senate in a 1909 primary election. At the time, legislatures still elected members of the United States Senate, but in Mississippi, a primary was held with the winner being elected by the state legislature. Williams faced the most formidable political challenge of his career from James K. Vardaman, the state’s governor. Vardaman cut a striking figure, tall, elegantly tailored, with a full head of black hair dramatically swept back from his forehead, which flowed over his collar. James K. Vardaman was also a violent racist and race-baiter. Vardaman had proven he was a mesmerizing orator of the old school and the race was both exceedingly bitter and close. Williams just barely won by 648 votes.

John Sharp Williams waited two years at Cedar Grove before beginning his term in the Senate. Much to Williams’ dismay, the senior senator from Mississippi, Anselm McLaurin, died suddenly and James K. Vardaman easily won the primary to take office in 1913. For six years, the two would sit together inside the United States Senate representing the people of Mississippi. John Sharp Williams and James K. Vardaman intensely disliked one another and their records were oftentimes diametrically opposed. Where John Sharp Williams was almost always a supporter of President Woodrow Wilson, James K. Vardaman never hesitated to oppose the president’s policies, especially Wilson’s foreign policy. As the United States drifted towards entering World War I, James K. Vardaman grew more alienated from the president and the Wilson administration.

Tradition required freshman senators to tend to their duties and remain largely silent. When John Sharp Williams traveled to Washington, D. C. and took his seat in the United States Senate on April 5, 1911, for a special session of Congress called by President William Howard Taft, the Mississippi senator ignored tradition. The Senate was debating a proposed constitutional amendment allowing the people to directly elect their own senators in popular elections. Williams was strongly in favor of the proposed amendment to the Constitution. Despite a gap of two years in his congressional service, a writer for the Saturday Evening Post, one of the country’s most popular publications at the time, wrote, “He is the same whimsical, delightful, brilliant chap he always was – – – absent-minded, preoccupied, unimpressed by any but the essentials, careless, happy-go-lucky and smarter than a steel trap.”

Williams received remarkably good committee assignments, especially for a freshman senator, being appointed to serve on the Finance and Foreign Relations Committees, both of which were much coveted posts. As a member of the United States Senate, John Sharp Williams’ mode of dress was once described as “carelessly fastidious” and he had a habit of strolling up and down the aisles of desks on the floor of the Senate. As he grew increasingly hard of hearing, the most familiar of gestures for the Mississippi senator was Williams cupping a hand behind an ear to hear better. Yet his mellow voice could always be heard in the galleries of the Senate Chamber.

John Sharp Williams was re-elected to another six-year term in the U. S. Senate in 1916 without opposition. James K. Vardaman became one of a handful of senators who opposed American entry into the First World War. Vardaman’s once great popularity with the people of Mississippi began to fade and he lost renomination in the Democratic primary to Congressman Pat Harrison, who enjoyed the backing of Senator Williams.

When President Woodrow Wilson nominated Louis Brandeis to serve as a Justice of the United States Supreme Court, it was quite a controversial appointment. Brandeis was Jewish and there was an element of anti-Semitism in some of the opposition to his nomination, but he was also an unabashed liberal for the time. Senator John Sharp Williams announced he would vote to confirm Brandeis to the high court, saying he did not believe a nominee’s views as an academic should be held against him; rather, Senator Williams contended, if the nominee were honest and a good lawyer, he should be confirmed by the Senate.

Without any opposition at home, Senator Williams was free to campaign on behalf of President Wilson, which he did. John Sharp Williams toured much of the Midwest, visiting Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin on behalf of the president’s candidacy. Williams traveled to the hamlet of Hodgenville, Kentucky along with Woodrow Wilson where they both spoke at the dedication ceremonies for the Abraham Lincoln birthplace shrine. Although a Southerner, John Sharp Williams was emphatic in saying Abraham Lincoln, like Thomas Jefferson, was one of the nation’s greatest Americans.

Senator John Sharp Williams also supported Woodrow Wilson’s unsuccessful crusade for the United States to join the League of Nations. Eventually, the Mississippian sighed and was prescient in saying it might very well take another world war to convince the American people of the necessity of an organization dedicated to preserving world peace.

John Sharp Williams was personally opposed to prohibition and was open in his own fondness for alcoholic beverages. Still, Senator Williams voted for the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution – – – the prohibition amendment – – – explaining the people he represented were for it while he was not. There were occasions when some accused Senator Williams of coming to the Senate floor after having enjoyed a cocktail or two. Once, Senator Thomas Heflin of Alabama hinted at Williams’ fondness for alcohol by sniffing that whatever else might be said of him, he always had his faculties when he came onto the Senate floor. “And what difference does that make?” John Sharp Williams roared in reply. Helfin’s original complaint was he had been interrupted while making a speech in Washington by an overhead airplane. “Why should anybody quarrel with a thing which makes noise in competition with a senator making a noise?” John Sharp Williams wondered. “They are both equally noisy and between the two the airplane is the more scientific noise.”

During a debate on the Senate floor, Wisconsin’s profoundly isolationist senator Robert LaFollette had just sat down after a lengthy diatribe. The slender figure of John Sharp Williams rose from his desk and began his own speech, saying, “Mr. President, if immortality could be attained by verbal eternity, the senator from Wisconsin would have already approximated immortality.”

Shortly after having been re-elected to a second term in 1916, Senator John Sharp Williams made the announcement he would not run again. Numerous friends and supporters repeatedly urged the Senator to change his mind, but Williams remained adamant, explaining he was becoming increasingly hard of hearing, which impaired his ability to serve the people of Mississippi in Washington. “I’m tired of it all and I’m going home to rest,” the senator told his friends. As to his plans, John Sharp Williams had very definite ideas of how he wished to spend his time; he would amble about the grounds of his plantation home, read books and “I want to stir myself a toddy, whenever I feel that I would like one.”

“And as night and time for bed approaches,” Williams said, “I will listen to the greatest chorus of voices that man ever heard, music that will charm me and make me ready for repose – – – the voices of my mockingbirds.”

John Sharp Williams stuck to his pledge and returned home to his plantation and Yazoo County. Williams spent nine quiet years in retirement, visiting with friends, answering his mail, and enjoying his family, especially his grandchildren.

The former senator cared little for the spotlight and once retired, rarely spoke in public. When a band comprised of boys wished to call at Cedar Grove, Williams replied in a letter, “I wish the dear old place could offer you something besides time to rest and a cordial welcome, but it cannot. You will get the welcome, however, and it will be cordially given from the heart.” The boys came and serenaded the old senator who did indeed extend a warm welcome. Mrs. Williams personally presided over a punch bowl of lemonade and served the youngsters herself. Williams promised he would visit the boys in Jackson, Mississippi. It was a promise John Sharp Williams never forgot and he kept it. Williams came to Jackson in 1924 and was visiting with a friend when outside the boys’ band began to play. Senator Williams came out to the porch and said, “I am too old to start telling lies to boys. I will speak for you now – – – wherever you wish.”

Williams had fallen the day after his 78th birthday and then again the next day. The last fall put the former senator in his bed for the few months remaining of his life.

John Sharp Williams was laid to rest beneath the nests of the mockingbirds he loved during his life and their descendants continue to sing to the old senator to this day.