By Ray Hill

Nathan L. Bachman is little remembered today, but was a highly regarded jurist and a popular United States Senator from Tennessee.

Bachman was born August 2, 1878 into a prominent family. He attended at least three colleges before setting out to earn a law degree. Bachman went to the University of Tennessee in Chattanooga before moving on to the University of Virginia where he actually earned his law degree. Bachman was named attorney for the City of Chattanooga in 1906, just three years out of law school. Bachman remained City Attorney until 1908 and began his political career in 1912 when he was elected a Judge of the Circuit Court. Bachman was elected to the Tennessee State Supreme Court in 1918 and stayed there until he resigned in 1923. Bachman left the high court to become a candidate for the United States Senate in 1924.

Incumbent U. S. Senator John Knight Shields was running for a third term, but his reelection prospects were hampered from the grave by the late President Woodrow Wilson. Shields had not especially liked Wilson and had been an opponent of America joining the League of Nations. If not actually obsessed by the League, Wilson was at least a passionate advocate of U. S. participation in the League of Nations. Wilson had been ready to denounce J. K. Shields during his 1918 reelection campaign when he faced a difficult challenge from Governor Tom C. Rye, but had been convinced to remain silent by Tennessee’s other U. S. Senator, Kenneth D. McKellar. Shields had won a narrow victory in the 1918 Democratic primary, but Wilson’s revenge was merely delayed.

Although severely disabled by a serious stroke, Wilson could still pick up a pen and sign his name. Wilson wrote a letter to a Tennessean shortly before his death stating Senator John K. Shields was no friend to him or his administration. Wilson was still highly popular in Tennessee and the former president’s declaration harmed Senator Shields’s candidacy in the Democratic primary.

The beneficiary of Wilson’s denunciation was not Nathan L. Bachman, but General Lawrence D. Tyson. Tyson, a former Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives and a hero of World War I, was quite wealthy and the owner of The Knoxville News-Sentinel, which the general had purchased largely to promote his candidacy for the United States Senate. Tyson spent lavishly on his campaign and defeated Shields rather easily. All three candidates were from East Tennessee; Tyson was from Knoxville, Shields from Grainger County and Bachman from Chattanooga.

Bachman demonstrated his popularity in his home county of Hamilton, winning 8,223 votes to a combined total of 1372 for Senator Shields and General Tyson. Bachman also carried Shelby County, although the machine lead by E. H. Crump had not quite gained the strength it would in just a few years. Bachman’s majority in Shelby County was only a few hundred votes and he was hard pressed by General Tyson. Davidson County was carried by Senator Shields, while General Tyson carried his home county of Knox. Overall, General Tyson beat Senator Shields by almost 20,000 votes with Nathan Bachman running third.

Bachman returned to his law practice and enjoyed a happy family life, being married to Pearl Duke, a relative of the fabulously wealthy James Duke who endowed the university of the same name. The couple had one daughter.

The victor of the hard fought 1924 primary, L. D. Tyson, did not live out his term of office, dying in 1929. Another Chattanooga was named to take Tyson’s place, millionaire candy-maker William E. Brock. Long-time Congressman Cordell Hull announced he would be a candidate for the U. S. Senate in 1930 and was elected. Hull only served two years in the Senate before being appointed Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hull resigned from the United States Senate, leaving newly elected Governor Hill McAlister the responsibility for appointing a successor.

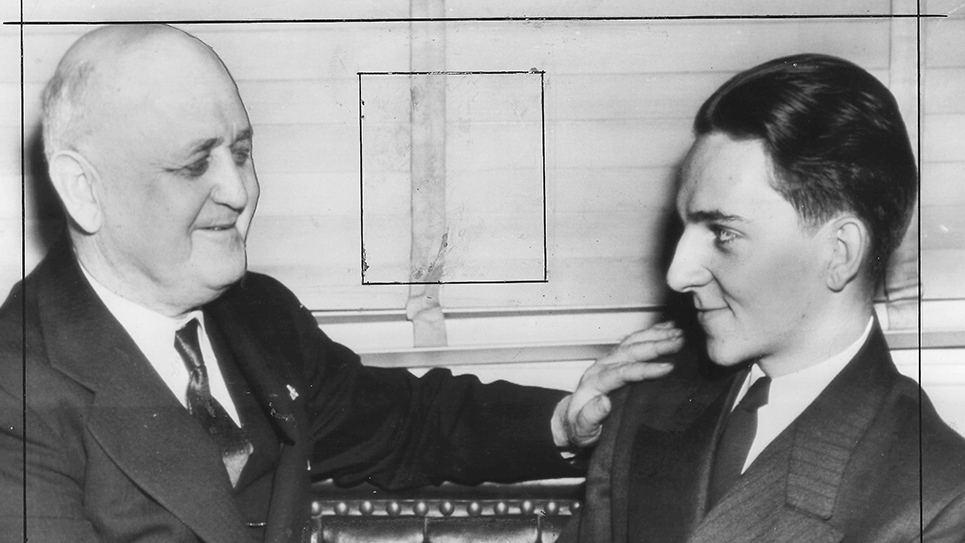

There was no lack of prospective candidates anxious to serve in the Senate and McAlister likely consulted with Tennessee’s senior United States Senator, Kenneth McKellar, before making an appointment. The governor appointed Nathan L. Bachman to fill the vacancy on February 28, 1933.

Nathan Bachman entered the Senate and clearly enjoyed his work. He also liked the camaraderie of the Senate and was soon quite popular with his colleagues. Bachman was apparently a repository of endless stories and anecdotes and soon won a reputation as one of the best storytellers in Congress. Bachman got along quite well with his senior colleague and seemed content to follow McKellar’s lead on appointments, patronage and most other matters. Bachman would have to face the voters in a 1934 special election to serve out the remaining two years of Cordell Hull’s term. Senator Bachman very much wanted to remain in the Senate and there was little doubt he would be a candidate.

Gordon Browning of Huntingdon, Tennessee, like many other Congressmen, ached to serve in the Senate of the United States. Browning had defeated two incumbent Congressman to serve in Congress, defeating Congressman Thetus W. Sims in the 1920 Democratic primary. Browning lost the general election in the 1920 Republican tidal wave that washed out several surprised Democratic incumbents, not the least of which was Cordell Hull. Browning, always persistent, came roaring back in 1922 to defeat GOP Congressman Lon Scott and remained in Congress for the next twelve years.

One of the unwritten rules of Tennessee politics was that no grand division (East, West and Middle) would occupy both of the state’s seats in the United States Senate. Bachman was from East Tennessee and Kenneth McKellar, who lived in Memphis, occupied the other Senate seat. Browning being from West Tennessee first started soliciting support to run against McKellar. Senator McKellar was then sixty-five years old and had been in the Senate eighteen years. McKellar was widely respected and highly popular in Tennessee and Browning would later admit he could not garner the first significant promise of support to challenge Senator McKellar.

Undaunted, Congressman Browning turned his sights on Nathan Bachman. Browning was unconcerned about violating the unwritten rule and felt that Bachman would likely be highly vulnerable in a primary contest. While Bachman had been elected statewide in 1918, he had lost badly to General Tyson for the Senate in 1924. It had been a decade since Bachman’s name had been on a Tennessee ballot. Browning announced he would run against Nathan L. Bachman in the primary and began an energetic campaign for the nomination.

An excellent speaker and able campaigner, Browning entered the race with the strong support of many veterans across the state. Browning was himself a veteran of World War I and had always given veterans and their concerns strong support as a member of Congress. Bachman’s chief asset during the 1934 campaign was his affable personality, his incumbency and the strong support he received from his senior colleague, K. D. McKellar. Senator McKellar, unchallenged for renomination in his own bid for another six-year term, was openly for Bachman. It was not long before Gordon Browning was complaining that Bachman’s reelection campaign was being run from McKellar’s Senate office.

McKellar, Bachman and Governor Hill McAlister, also a candidate for renomination, traveled the State of Tennessee, campaigning as a team while the insurgent Congressman Browning accused Senator Bachman of being a pawn of McKellar, as well as lazy. Browning made a race of it, but lost to Senator Bachman by more than 40,000 votes. Bachman carried each of the four big urban counties – – – Shelby, Davidson, Hamilton and Knox. Browning carried his Congressional district and did well in much of Middle Tennessee.

Senator Bachman would face the voters again in 1936 for a full six-year term and his defeat of Gordon Browning discouraged others ambitious to serve in the Senate to wait on the sidelines. Browning himself was attempting a comeback by running for the gubernatorial nomination. Nathan L. Bachman had no serious opposition in his campaign for the six-year term and he was renominated and reelected.

The 1936 election was have serious repercussions for the next several years and eventually lead to one of the most bitter contests inside Tennessee’s Democratic Party in history. Browning was elected governor with the support of E. H. Crump and the Shelby County machine over the opposition of Senator McKellar. Nathan L. Bachman would return to Washington, D. C. and take the oath of office for a new term. Senator Bachman only served a little over three months of that new term, dying of a sudden heart attack at his Washington, D. C. hotel apartment on April 23, 1937. Senator Bachman was only fifty-eight years old when he died.

Senator McKellar led a delegation of Congressional mourners to attend Nathan Bachman’s funeral and TIME magazine noted there was already considerable conversation about who would succeed to the late senator’s seat. Governor Gordon Browning was besieged by those wanting to give him advice about the senatorial appointment as well as those who believed they would make a mighty fine senator. Browning was even summoned to the White House by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who later said he did not tell Browning whom to appoint, but rather whom not to appoint.

Governor Browning later went to Memphis to meet with Boss Crump to discuss the senatorial appointment and that fateful meeting would be the genesis of the warfare that erupted between two factions of the Tennessee Democratic Party.

There was a school on Signal Mountain, where Bachman lived, named for him which ceased to operate in the late 1990s. The highway tunnels connecting Chattanooga to East Ridge were named the Bachman Tubes in honor of Senator Bachman. The senator’s only child, his daughter, Martha, continued to live on Signal Mountain and was recognized for her extraordinary sense of community spirit. While Nathan Bachman did not serve in the United States Senate long enough to accomplish a great deal, he was uniformly kind, cared deeply about his state and her people, and worked hard at the numerous tasks demanded by a people then suffering from the deprivations of the Great Depression.