From the author’s personal collection.

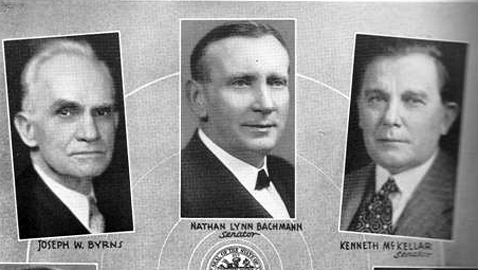

The Tennessee Congressional delegation in 1935. Congressman J. Ridley Mitchell is on the far right, second row.

By Ray Hill

Following the demise of Governor Gordon Browning’s plan to emasculate the Shelby County political machine headed by E. H. Crump, Tennessee Democrats were deeply divided. Governor Browning watched with dismay as his appointee to the United States Senate, George L. Berry, continued his feud with the Tennessee Valley Authority. Berry wanted significant compensation from the TVA for mineral leases and marble deposits on land flooded by Norris Dam.

Kenneth D. McKellar, Tennessee’s senior United States senator, was busy keeping up with political sentiment in his home state. McKellar knew all too well that if Gordon Browning were reelected governor in 1938, he would face a serious challenge for renomination to the Senate in 1940. McKellar was bound and determined to see that Browning was defeated. His political ally and partner, E. H. Crump, still smarting from the battle with Governor Browning, deferred to the senator in selecting candidates to oppose Browning and Berry.

Crump’s handpicked successor in Congress, Walter Chandler, announced that he would be a candidate for the gubernatorial nomination. Evidently, Congressman Chandler had not fully discussed his aspirations with either McKellar or Crump, as the Memphis Boss was uneasy about the notion of a candidate for statewide office from his own domain. McKellar was, at best, lukewarm to the idea of a Chandler candidacy and the Congressman endured the embarrassment of having to withdraw in a matter of days.

In the fall of 1937, a new airport was being dedicated in Kingsport, Tennessee. The new airport was to benamed for Senator K. D. McKellar and a crowd of some 15,000 was expected to attend the dedication ceremonies. Ostensibly a non-political event, just about every important politician in the state was on hand for the ceremonies. McKellar, being the honored guest, was the main speaker. A special platform was built on the tower and a powerful microphone amplified the senator’s voice. Governor Gordon Browning and Senator George L. Berry also attended, having to tolerate an enormous crowd honoring McKellar.

Senator Berry, anticipating the coming 1938 primary, was moving around the state more frequently and he spoke in Jackson where he warned that the dictators in Europe would almost certainly cause another World War.

The most persistent of the possible candidates to oppose Senator Berry was Fourth District Congressman J. Ridley Mitchell. Mitchell, a sixty-year old bachelor from Cookeville, was a veteran of Tennessee politics, having served for six years as District Attorney and seven years as a Circuit Court judge before winning a seat in Congress in 1930. Mitchell demonstrated considerable political skillsin his 1932 reelection campaign when he faced another incumbent after his district had been combined with that of another Congressman. Mitchell’s opponent, Ewin L. Davis, had been in Congress twelve years and chaired a committee in the House of Representatives. Mitchell beat Davis and was easily reelected in 1934 and 1936.

Mitchell’s successor in Congress, Albert Gore, Sr., described the Congressman as being the sort of politician who could promise every constituent a new post office and then make that constituent happy when the new post office never materialized. Tall, bald, stately, and an able speaker, Mitchell was determined to be a candidate for the United States Senate.

Congressman Mitchell evidently did not journey to Memphis to ascertain the attitude of Mr. Crump, but he did approach Senator McKellar. Mitchell discovered McKellar intended to back a “coalition” ticket for governor, U. S. senator, and Utilities Commissioner in the coming primary. Congressman Mitchell was wary of alliances in Tennessee politics and left McKellar’s office without any promise of support. It was soon clear McKellar had no intention of backing Mitchell, as the senator was still sorting through possible contenders to challenge George L. Berry.

McKellar wanted Winfield Hale of Rogersville to run; Hale was a highly respected judge and a long-time supporter of the senator. Hale’s daughter, Sarah, was a McKellar secretary and the senator’s regard for the judge was immense. Judge Hale informed McKellar he could not make the race and when it became apparent Third District Congressman Sam D. McReynolds would not enter the primary, the senator turned his attention to Arthur T. “Tom” Stewart of Winchester.

As rumors circulated throughout Tennessee as to the possible candidacies of numerous Democrats, the Nashville Banner, a newspaper highly friendly to McKellar, hinted that Tom Stewart was preparing to make an announcement of his own campaign. Stewart had done nothing to prepare for a Senate race and the Banner flatly stated Stewart’s candidacy was prompted by Senator McKellar. The Banner quoted “sources as saying”, “It is only at the insistence of the Senator and McKellar men generally over the state that Stewart has agreed to get into the Senate contest.”

On March 4, 1938 Congressman J. Ridley Mitchell made his candidacy for the United States Senate official. Mitchell’s Secretary, John Elrod, said the Congressman would speak throughout Tennessee starting in June and might speak as frequently as twice a day. Congressman Mitchell later enlarged upon Elrod’s announcement, saying he would campaign in each of Tennessee’s 95 counties and would “make as many speeches and as many visits as it takes to meet all the people.” Oddly, Congressman Mitchell also announced he would employ the use of an “electric calliope” to provide music for his campaign and entertain voters.

Congressman Mitchell formally opened his campaign for the senatorial nomination on May 28, 1938 with a speech in Murfreesboro, which was inside his own Fourth Congressional District. Mitchell positioned himself as the “harmony” candidate, much as K. D. McKellar had in 1916 when facing Senator Luke Lea and former Governor Malcolm Patterson. Mitchell proclaimed himself as the only candidate who could restore harmony to the badly fractured Tennessee Democratic Party. Congressman Mitchell carefully noted he was not affiliated with any particular faction and could better represent Tennessee without any political alliances or obligations.

Mitchell used his speech to criticize Senator McKellar.

“If the senior senator of our state and some two or three other temporary time-serving officeholders, henchmen and city bosses can name the junior senator from our state, then such senator would have to obey the commands of his creator. He would have to obey his master’s voice,” he stated.

Congressman Mitchell claimed with such a beholden senator, “Your interest, the party’s interest, the state and nation’s interest would suffer as a result.”

J. Ridley Mitchell was careful to say that he personally had a high regard for Tom Stewart, who was a resident of Mitchell’s Congressional district. Still, Mitchell cautioned that Stewart had “permitted himself to be handpicked and labeled.”

Mitchell claimed Stewart had been anticipating being appointed to a Federal judgeship prior to being summoned by “the bosses” who “called on him to wear their collar and bear their label.” Mitchell complained about the coalition ticket formed by the McKellar – Crump alliance of Prentice Cooper for governor, Tom Stewart for U. S. senator and W. D. “Pete” Hudson for Utilities Commissioner. Mitchell said such a coalition campaign was “something unheard of in Tennessee politics.”

Congressman Mitchell tried hard to make his lack of support from a particular faction of the party into an asset, saying: “The only sin I have committed in the eyes of those who oppose me is that I would not become a factional candidate.” Mitchell wondered why he should be expected to meddle in other races?

Mitchell returned to his criticism of Senator K. D. McKellar, thundering, “There is no reason why one senator from our state should seem to name and dictate who will serve as his colleague.”

“Why not let the people elect their own senators?” Mitchell cried.

Congressman Mitchell admitted to having visited Senator McKellar, although his description of that visit certainly fit into the context of his insistence that the senior senator intended to name his future colleague. According to Mitchell, McKellar had proceeded to “insist” that the Congressman would “have to become a factional candidate in the governor’s race and have to open a common headquarters with other candidates who he would name if I was to expect his support.”

Mitchell righteously said he did not know if Senator McKellar intended to support him, but declared he had refused to be “a party to any such scheme.”

The Congressman took a last dig at McKellar, saying if he was elected to the Senate, he would not seek to control patronage. Mitchell stated Tennessee needed a “New Deal” in political patronage, not a factional deal.

“Patronage is not the personal property or chattel of anyone in office,” Mitchell intoned.

In truth, Congressman Mitchell knew McKellar had no earthly intention of supporting his senatorial ambitions. Aside from both Mitchell and McKellar being bachelors and Democrats, the two men had little in common. Senator McKellar was forthright to the point of being blunt, while Mitchell was a wily politician who frequently calculated his positions for the widest popular appeal. McKellar would flatly tell constituents he disagreed with them, while Mitchell was quite adept at telling his listeners what he thought they wanted to hear. Neither man had much liking for the other and Mitchell had proposed a bill forbidding the hiring of relatives and McKellar’s own Secretary was his younger brother, Don. Don had also married another McKellar staffer, Janice Tuchfeld, who remained on the senator’s payroll. McKellar’s older brother, Clint, was also still the Postmaster of Memphis.

Mitchell did not ignore the incumbent, Senator George L. Berry, in his opening speech. The Congressman claimed Berry “is too busy playing marbles and selling land to the government and opposing the President and the New Deal to look after his race.”

Senator Berry, once a stalwart of the New Deal and a staunch supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt did indeed seem to have undergone a change of attitude. That attitude was noted, especially by his political opponents, who claimed Berry had parted ways with Roosevelt.

Speaking in Johnson City, Senator Berry denied he had broken with President Roosevelt and the New Deal, although he did admit to “differing with FDR on some issues.”

Still, George L. Berry was making some distinctly conservative sounding utterances on the campaign trail, which were at odds with the New Deal administration of Franklin Roosevelt.

Berry told a Memphis audience, “I have been opposed and am now opposed to the Federal government engaging in business competitive enterprise.”

Prior to his opening speech in Murfreesboro, Congressman J. Ridley Mitchell had made a tour of East Tennessee, an area that was predominantly Republican, but also the home of Senator Berry. Mitchell was little known in East Tennessee and he visited Kingsport, Elizabethton, Bristol, Morristown, Johnson City and Greeneville. Mitchell tried to meet as many important Democrats as possible, but it would prove to be a difficult area for him to harvest votes. Aside from being Senator Berry’s home territory, East Tennessee was an area where Senator K. D. McKellar was enormously popular. McKellar’s political organization was extremely strong in East Tennessee and whatever strength he possessed would be used on behalf of Tom Stewart.

The Democratic primary for the U. S. Senate in Tennessee was just beginning to get under way.