Appointing a Senator: John D. Hoblitzell Jr. of West Virginia

The process for replacing congressmen and U.S. senators is quite different. When a congressman resigns or dies in office, that vacancy must be filled by calling a special election. When a member of the United States Senate resigns or dies in office, the governor must appoint a successor who serves until the next election. In Tennessee, the Class I seat has never had a vacancy in modern times. In fact, since 1911, that particular seat has had only eight occupants to this date. Of course, one of them was Kenneth D. McKellar, who held the seat for thirty-six continuous years. By contrast, the Class II seat from the Volunteer State has had nineteen occupants during the same time frame. Six of those occupants were appointed to fill vacancies.

Those appointed to the United States Senate are free to run to hold the seat, although some governors purposely appoint someone with the clear understanding he or she will not run in the next election, but rather hold the seat until the people have elected a replacement.

Matthew Mansfield Neely had held every office the people could elect him to of importance in his home state of West Virginia. Neely was the political Lazarus of his age; he could suffer a defeat and come roaring back in the next election. At various times, Neely was elected to the House of Representatives, the United States Senate, the governorship, to the House once again, and made a triumphant return to the Senate in 1948. Neely was reelected in 1954 at age eighty. Senator Neely seemed to be in relatively good health when he was elected to his final term but by 1956 he was ailing. Neely had undergone an operation on his prostate, which may well have been for cancer. That November, Neely fell and fractured his hip.

His colleague Harley Kilgore had died and a 1956 special election saw Republican Chapman Revercomb returned to the U.S. Senate by the people of West Virginia. Revercomb had defeated then-Governor Neely in 1942 to serve a six-year term. Neely came back in 1948 to beat Revercomb. The two served together briefly. Neely, who had lost three fingers on his left hand to cancer, was suffering from the dread disease once again. Harry McPherson, a young aide to Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, recalled his feeling there was even then something of the mines and hollows of West Virginia about old Matt Neely still. The 83-year-old senator suffered from cancer for eighteen months before finally dying on January 18, 1958, in Bethesda Naval Hospital.

As is usually the case, the incumbent’s body is hardly cold before speculation in the news media begins about the potential successors. Neely was no different and the same day the Beckley, West Virginia Post–Herald and the Raleigh Register printed an obituary for the dead senator, they also printed an article about a prospective successor.

1956 had been a big year for Republicans in the Mountain State. Not only had Chapman Revercomb been reelected to the U.S. Senate, but President Eisenhower had carried the state and the GOP had elected Cecil Underwood governor. Underwood was the youngest man ever to be elected governor of West Virginia, being 34 years of age when he won his first term. Underwood remarkably is also the oldest man ever to be elected governor of West Virginia, winning his second term 40 years later on his 74th birthday. A former high school teacher who had been elected to West Virginia’s House of Delegates, Underwood won an upset victory over a nominee who was a protégé of Matthew Neely.

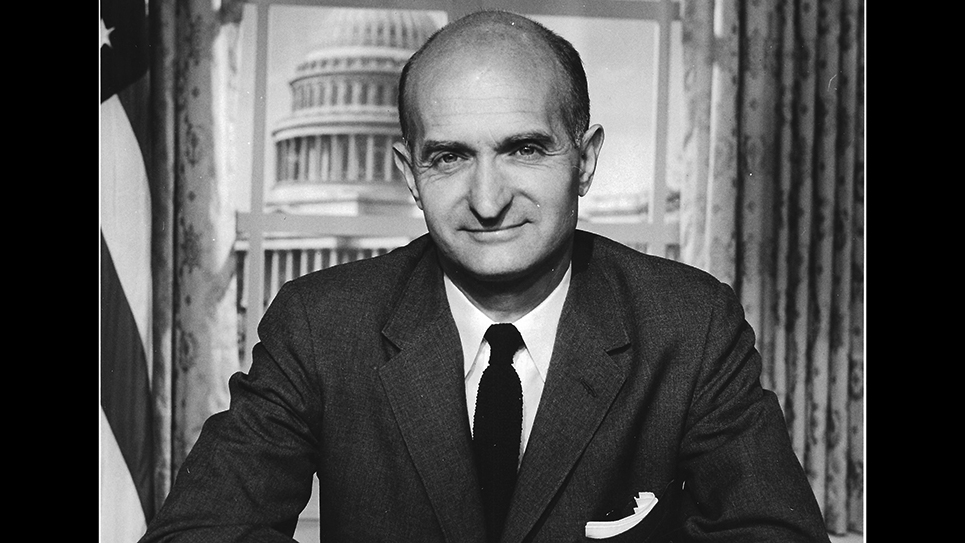

The name most prominently mentioned in the speculation as to who would succeed the colorful Neely centered around John D. Hoblitzell Jr. Hoblitzell was the chairman of West Virginia’s Republican Party. A businessman from Ravenswood, Hoblitzell had raised money and worked hard for the GOP ticket and its success in the general election. Immediately following Senator Neely’s death, neither Governor Underwood nor John Hoblitzell would comment upon the rumors about the latter being appointed to the United States Senate. The governor said he would not consider the appointment until after Senator Neely’s funeral. That consideration and respect for the late senator and his family did not stop the speculation in the daily newspapers. For the first time in 30 years, West Virginia would have two Republican United States senators.

When Senator Harley Kilgore died in 1956, Governor William Marland appointed attorney William R. Laird III, who was an old friend from college. As Marland was a candidate for the U.S. Senate in the 1956 special election, Senator Laird served as a placeholder until the voters chose between the candidates. In 1958, the situation was different, although there was some speculation Underwood might opt to run for the Senate, although most political observers thought the governor would remain in Charleston as he still had two years remaining on his term as the state’s chief executive.

Governor Underwood considered several prominent West Virginians for the senatorial appointment, including Helen Holt, the widow of former U.S. Senator Rush Holt, a Democratic firebrand who had become a Republican and had quite nearly been elected governor in 1952. Some years later, Underwood told me some of those he had considered for the appointment to the United States Senate were bitterly disappointed when they did not receive it and never spoke to him again.

Hoblitzell was sought out by reporters, who asked if he would accept appointment to the U.S. Senate should Governor Underwood offer it. Jack Hoblitzell carefully replied, “anyone interested and involved in politics would consider it a high honor to be appointed to the Senate.” Hoblitzell then reminded the reporters, “It will be the governor’s decision and I will abide by the decision and work for whoever is appointed.” Cecil Underwood and John “Jack” Hoblitzell were friends of longstanding, and few were surprised when the announcement came.

Governor Underwood made the announcement with the kind of flair Matthew Neely would have appreciated. Underwood made known his choice in a 30-minute live press conference on television. At the mid-point of the news conference, the 45-year-old banker and real estate man walked into the room. Hoblitzell readily acknowledged the weight of serving in the United States Senate, saying he was fully aware of the “awesome responsibility” of the office. Underwood had stated in his press conference his appointee would be a candidate in the 1958 election. Hoblitzell reiterated his intent to run, saying he had already started his campaign for the Senate and would soon file his candidacy officially with the secretary of state. A reporter quizzed the governor about 1960, inferring the senator might step aside so Governor Underwood, who could not succeed himself, might run for the Senate. “Any speculation about 1960 is just that – – – speculation,” Underwood replied. “If you are trying to intimate that a deal has been made, there is none.”

While it was certainly true Jack Hoblitzell was a loyal and active Republican and had done yeoman work in helping the GOP state ticket to victory in 1956, it was also equally true the newly appointed senator had, at best, a spotty electoral record. Hoblitzell had run for Congress in West Virginia’s Fourth District in 1956 against former Congressman Will E. Neal, who was seeking to make a political comeback. Neal won the Republican primary and went on to win the general election. 1958 was not looking to be a banner year for Republican candidates as the country was in the midst of a painful economic recession and both of West Virginia’s seats would be up for election that year. Senator Chapman Revercomb had already demonstrated his vote-getting prowess when he had won a six-year term in the U.S. Senate in 1942 by beating the best vote-getter amongst the Democrats in the Mountain State, Matthew M. Neely. While Revercomb had lost his reelection bid in 1948 and another in 1952, Chapman Revercomb was very well known to West Virginians and was a highly popular figure, especially in Republican circles.

West Virginia Democrats were well aware of the vulnerability of the Republican candidates, which encouraged strong candidates to run. Congressman Robert C. Byrd of Charleston announced he would challenge Senator Revercomb for the full six-year term. Byrd even then was a formidable campaigner and had served six years in the House of Representatives. Byrd had no serious opposition inside the Democratic primary. The contest for the Democratic nomination for the seat held by Jack Hoblitzell was a fight between former governor William Marland, who had been defeated by Chapman Revercomb two years earlier, and former congressman Jennings Randolph of Elkins. Randolph had first been elected to the House of Representatives in 1932, riding the tidal wave that was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s campaign. Jennings Randolph, named for William Jennings Bryan, had served in Congress during the first one hundred days of the New Deal. Randolph remained an old-time New Deal Democrat and was an able speaker, having taught public speaking as a college professor. Jennings Randolph had been elected and reelected to seven terms as a congressman, finally losing in another tidal wave election in 1946. That year, Republicans campaigning on the slogan “Had Enough,” got solid support from American voters tired of the deprivations and sacrifices made to win the Second World War.

Out of office, Jennings Randolph became a lobbyist for the airline industry. Randolph wisely kept up his ties to West Virginia and the Mountain State’s Democratic primary. Former Governor William Marland had been the youngest person ever to be elected chief executive of West Virginia before Cecil Underwood claimed that title for himself in 1956. Marland’s term as governor had been turbulent and his proposed tax on the coal industry had started a brutal fight in the West Virginia legislature. Marland had only narrowly defeated Attorney General John Fox inside the Democratic primary in 1956 and lost the general election to Revercomb. Seeking a comeback in 1958, Marland’s stormy term as governor did little to help him and Jennings Randolph won the Democratic nomination easily.

Chapman Revercomb almost did not seek reelection to the U.S. Senate, as he very much wanted a federal judgeship. What Senator Revercomb may not have known is his hopes for a judgeship were undermined by his own party. Governor Underwood and Senator Hoblitzell thought Revercomb too old to be appointed to a federal judgeship and gave him only lukewarm support. The appointment never materialized. Ironically, Chapman Revercomb would outlive the much younger Jack Hoblitzell.

Robert Byrd and Jennings Randolph ran as a duo in 1958 while Chapman Revercomb and Jack Hoblitzell cooperated, but each was running his own campaign. The 1958 elections were disastrous for Republicans, who lost thirteen seats in the United States Senate, including two in West Virginia.

Jack Hoblitzell left office in November when Jennings Randolph was certified the winner of the special election, making him West Virginia’s senior senator. Robert Byrd would remain in the U. S. Senate for the next 51 years, making him the longest-serving senator in our country’s history.

Hoblitzell remained active in business and politics. He died of a massive heart attack in 1962; he was only 49 years old.

Chapman Revercomb became a candidate for the GOP nomination for governor in 1960 and considering his large following inside West Virginia’s Republican Party, it took the open and determined opposition of Governor Cecil Underwood to stop him. It left a bad taste in the mouths of many Republicans and Underwood lost the Senate race that year, the gubernatorial race in 1964, the GOP nomination for governor in 1968 and a humiliating loss to Jay Rockefeller in 1976. Underwood’s political career was revived twenty years later when he was urged to run and was again elected.

All politics is local and even a pebble tossed into the pond ripples back to the shore.

© 2023 Ray Hill