Behind the Curtain: Women Come Into Their Own

With women occupying a majority of the seats on the Knox County Commission and the recent centennial of Tennessee being the state to give women the right to vote, it occurred to me to write a column about some women who were prominent, yet largely unknown. There was a time when congressmen and senators only employed women in a secretarial capacity; at that time, those were usually known as “stenographers” but there were several men who had mastered the relatively new art of the typewriter. Before women got the right to vote, it was almost unheard of for women to occupy the highest staff position in a congressman or U.S. senator’s office.

Tennessee’s first popularly elected United States senator was Kenneth D. McKellar. McKellar, while a life-long bachelor, was highly supportive of women and was a strong advocate of ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, giving women the right to vote. One of the most notable of Tennessee’s suffragists was Sue Shelton White, who worked on McKellar’s Senate staff. At the time, the top staffer in a congressman or senator’s office had the title of “secretary,” which was the equivalent of today’s chief of staff. Even the top staff member to the president of the United States was referred to as the secretary. McKellar named Miss Shelton as his top staffer. Eventually, Miss Shelton left McKellar’s staff and became a practicing attorney, although she returned to federal service under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Some of the women who rose to the top staff positions on Capitol Hill became powerful in their own right. Catherine Blanton was a girl from Sikeston, Missouri, who learned to type and that skill, as well as a determined work ethic and a native shrewdness took her all the way to Washington, D.C. Miss Blanton’s first secretarial job was part-time while she was in high school. In 1925, Miss Blanton left Christian College, where she was the secretary to the president of the institution, to go Capitol Hill with Congressman William L. Nelson. She became the top assistant to Congressman Nelson. Catherine Blanton remained in Washington and the center of events through the administrations of Presidents Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. While working for Congressman Nelson, Miss Blanton later recalled, “Since I was permitted to close up the office any time a senator of note was scheduled to make a speech, I heard many orations made by Sen. James A. Reed of Missouri, Sen. Pat Harrison of Mississippi and Sen. William E. Borah of Idaho.” In 1929, Miss Blanton became the chief of staff for Senator Pat Harrison, a gregarious and influential senator who became even more so during the New Deal when he chaired the Senate Finance Committee. Harrison failed to become Senate Majority leader by a single vote, losing to Alben Barkley of Kentucky in 1937.

“Particularly do I recall the time I escorted two dear Mississippi friends of Senator Harrison’s down to greet President Franklin D. Roosevelt,” Miss Blanton remembered after celebrating at her retirement party. “We had been allotted five minutes. And – – – while I thought I was sophisticated – – – when we were about to leave, he asked me to come over to his desk, put out both his hands, and I placed mine in them. He looked up at me, giving me his famous smile, with, ‘Well, this is the little girl I have heard Pat say so much about!’ I wilted under his charm as did everyone else.”

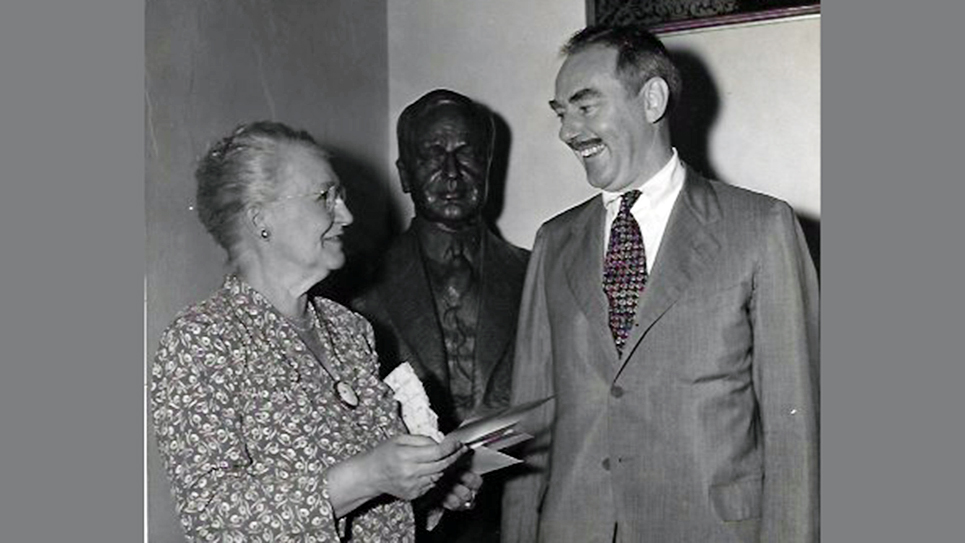

Senator Harrison, after having been either in the House of Representatives or the United States Senate for thirty years, died of stomach cancer in 1941 at age fifty-nine. Miss Blanton left Capitol Hill and became the manager in Washington, D.C., for General Motors. Catherine Blanton married James O’Connor Roberts in 1946, who was a very prominent attorney. Roberts died in 1952 and his widow decided to go back to what she loved best: politics and Capitol Hill. Stuart Symington was a freshman U.S. senator from Catherine Blanton Roberts’ home state of Missouri, having beaten Republican incumbent James P. Kem. When Symington took office in January of 1953, Catherine Blanton Roberts joined the new senator’s staff as the senator’s executive assistant. “Working for Senator Symington was not like being with a ‘first term’ senator, since he had served in so many official positions under President Truman,” Mrs. Roberts explained to a reporter.

An old pro, Mrs. Roberts attended the 1956 Democratic National Convention with Senator and Mrs. Symington. Catherine Blanton Roberts began experiencing problems with her health. “Not being able to spend a full day at the office was most frustrating, and for that reason, I finally persuaded the senator to permit me to retire,” Mrs. Roberts explained. When she retired, Senator Symington paid tribute to her long years of service.

“The days of the New Deal were my most thrilling,” Catherine Blanton Roberts confessed, “but I’ve actually loved every minute of it.”

“No one in this government is more highly respected or has more friends than Catherine Roberts. Her leaving government will be a deep loss, not only to me and her host of friends on the Hill, but also to thousands of Missourians for whom she has worked ably and well over the years,” Symington said.

Catherine Blanton Roberts suffered from osteoporosis of the spine severely enough that she had to wear a body cast. Retiring in 1965, she died suddenly in 1968. Mrs. Roberts was the youngest sister of many siblings and one brother, who published the Daily Sikeston Standard newspaper in their native Sikeston, lamented the loss of the sister of whom they had been so proud.

Marshall Adams once wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Capitol Hill in Washington never has been likened to a stage set; actually, it is the biggest performance, with the most exciting cast of characters and the most interested audience, of all time.” Certainly, Ruth Overton looked very much like one of the glamorous movie stars of the 1940s. Yet Miss Overton was one of the players in Washington, D.C., where she served as the chief of staff to her father, United States Senator John Overton of Louisiana. Beautiful and blonde with a low-pitched voice, Miss Overton was charming enough to calm those constituents with a bone to pick. Privately, Ruth Overton was involved in a relationship with Warren Magnuson, a congressman and senator from Washington State.

Miss Overton had been beautiful and talented enough to be associated with show business. She appeared on Gary Moore’s radio program several times and had been under contract to the CBS radio network. Ruth Overton had once been selected as queen of Washington’s Cherry Blossom Festival.

Warren Magnuson’s biographer, Shelby Scates, quoted Mrs. Herbert Kraushaar about Ruth Overton: “She was smart, sophisticated, and lived much of the time in Washington where her father was in the Senate. She was very lovely and gracious, outgoing but not pushy – – – a lady, a Southern lady.”

The affair with Magnuson, like most of Magnuson’s relationships with women, blew hot and then cold. Ruth Overton had less tolerance for other women in her beau’s life. “She was not old-maidish,” Mrs. Kraushaar remembered, “but I don’t think she had another serious romance after she came back to Alexandria, after the congressman.”

It was very serious with Magnuson. She lived in the old family home, never married, not to the congressman or anyone else. Her father, Senator Overton, ended it. He told her he did not think Magnuson would ever amount to anything. She could not go against her father’s wishes.

Senator John Overton died in 1948 following surgery for an abdominal obstruction. Ruth Overton returned home to Alexandria, Louisiana. An Overton family member coming into the old home late one afternoon in 1973 smelled an unusual and sickening smell. Realizing what it was, the family member hurried up the stairs and rushed into Ruth’s room rolled her off the burning mattress and put out the fire. Ruth Overton died from her injuries. She was only sixty years old.

One of the powers on Capitol Hill was Nevada’s United States Senator Pat McCarran. McCarran headed the Senate’s powerful Judiciary Committee and he was a fierce anti-Communist. Silver-haired and portly, McCarran dominated his home state’s politics, largely due to his excellent constituent service and formidable staff. McCarran’s chief assistant for years was Eva Adams. Ms. Adams was remarkably efficient, and McCarran’s staff was acknowledged by veteran Capitol Hill observers as one of the best in government. Senator McCarran, aided by his staff, was relentless in his efforts to help a fellow Nevadan. McCarran’s machine in Nevada had become a bit wobbly and the 78-year-old senator was facing political difficulties. Hoping to cobble together a peace inside Nevada’s Democratic Party, McCarran was campaigning for the Democratic ticket when he fell over dead of a massive heart attack at a rally in Hawthorne, Nevada, in 1954.

McCarran, who could be a trial to work with, once imbibed too much at the open bar of the secretary of the Senate one evening. Returning to his office, McCarran dictated a slew of obnoxiously rude telegrams to the most important people in Nevada. The next morning the senator came to his office shaky and white-faced. “My God, did you send those telegrams?” Senator McCarran asked Adams. She snapped, “No, and I’m resigning!” McCarran began to laugh. “You don’t have to resign and thank you for not sending them.”

Eva Adams’ well-deserved reputation for efficiency kept her in the top staff position under Republican Ernest Brown, who was appointed to succeed McCarran briefly, before losing the general election to Democrat Alan Bible. Bible was reelected to a full six-year term in 1956, but Senator Bible and Eva Adams never got along particularly well. Bible realized Adams had made a host of friends throughout the Silver State throughout her time in Washington and firing her would carry enormous political fallout. Senator Bible urged President John F. Kennedy to appoint Adams as the director of the United States Mint. In 1961, John F. Kennedy invited Eva Adams to lunch at the Senate cafeteria and asked her to serve as director of the Mint. Because precious metals ranked at the top interests of any Nevada politician, Eva Adams had a keen understating of many of the issues important to the Mint. The U.S. Mint experienced its fastest growth under Eva Adams.

Miss Adams was reappointed in 1966 by Lyndon Johnson and served until 1969 when she became a special advisor to the chairman of the board of the Mutual of Omaha Insurance Company.

Miss Adams once said in her day, a woman working as an administrative assistant (chief of staff) was expected to “dress like a Queen, act like a lady, think like a man, and work like a dog.”

Cordell Hull’s time in Washington as a congressman, U.S. senator and as our country’s longest-serving Secretary of State saw his primary assistant Miss Will Harris move from one office to another. Miss Will was a native of Livingston, Tennessee, and although she remained behind at the State Department after Hull’s retirement in November of 1944, she worked only a few months longer. After that, she returned to working for Cordell Hull in his declining years. Miss Will Harris had been employed by A. H. Roberts, an attorney who served a term as governor of Tennessee from 1919 to 1921. Miss Will frequently traveled with Mr. Roberts by horse and buggy when he practiced law in the courts of neighboring counties. After his election to Congress in 1904, Hull approached Roberts and asked for his permission to hire Miss Will Harris. Hull reassured a very reluctant Roberts he only expected to be in Congress for a few years.

That few years turned out to be fifty.

© 2023 Ray Hill