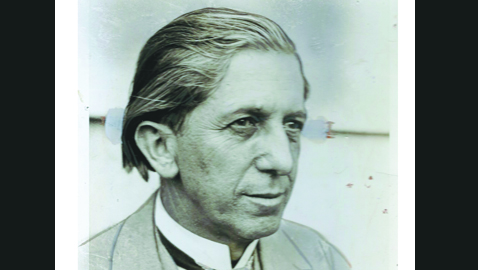

For decades, Clyde Roark Hoey was one of North Carolina’s most personally popular politicians. Even well before his death, Clyde R. Hoey was something of a caricature. Always immaculately dressed, Hoey favored a frock coat and bat-wing collar long after the style had fallen out of fashion. Hoey wore his hair long and as he aged, it turned white and flowed over his collar. Certainly, his appearance was remarkable and if he wished to be noticed, Hoey succeeded admirably. Clyde R. Hoey was almost invariably pointed out by visitors in the Senate Gallery. Hoey may have also had the most appropriate name for a politician in history (pronounced HOO-ee).

Clyde R. Hoey won virtually every office within the gift of the people of North Carolina, serving as a congressman, governor, and United States senator. Hoey was part of the “Shelby Dynasty”, a successful political machine that ruled state government in North Carolina for twenty years. The origin of the machine was Shelby, North Carolina whence it got its name. There was an informal agreement between Democratic Party leaders the governorship would alternate between the eastern and western sections of the state. The first governor to be elected by the Shelby machine was O. Max Gardner, who was Clyde R. Hoey’s brother-in-law. Both Gardner and Hoey had married well; Gardner was married into the politically powerful Webb family, while Hoey had married Gardner’s sister, Bess.

Gardner earned a reputation as a most able and excellent governor. Gardner was succeeded as governor by John C. B. Ehringhaus, who was in turn succeeded by Clyde R. Hoey.

Born December 11, 1877 in Shelby, Clyde R. Hoey received little formal education. After age eleven, Hoey spent most of his time working on the family farm, although at twelve he became a printer’s assistant. Evidently he saved his money, as he bought a weekly newspaper when he was only sixteen years old. Hoey began studying law and was admitted to the Bar.

Hoey adapted quickly to politics, winning his first election to the North Carolina House of Representatives when he was twenty. Four years later, Hoey was elected to the State Senate. When the Democrats won the presidential election in 1912, Clyde R. Hoey was appointed as assistant U.S. attorney the following year.

Hoey won a seat in Congress after Representative Edwin Y. Webb had resigned to accept an appointment to a federal judgeship. Hoey only served two years in Congress, choosing to return home to North Carolina and his business interests and law practice.

Hoey was the candidate of the Shelby machine in the 1936 to run for governor. His path to the governor’s mansion was not an easy one, as he faced fierce competition from Ralph McDonald. Hoey’s campaign was seriously complicated by the record of his predecessor, Governor Ehringhaus, who had successfully forced a sales tax through the North Carolina legislature. The battle over the imposition of a sales tax was hard fought and McDonald had been one of the leaders against the new tax. An effort was made to repeal the sales tax and Governor Ehringhaus had to use every means at his disposal to preserve the new revenue flowing into the state’s nearly empty coffers.

McDonald was an unusual politician for North Carolina; he had only lived in the state for twelve years, having been a college professor in Illinois before moving to the Tar Heel State. McDonald was an enthusiastic supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. The leaders of the Shelby machine were outwardly supportive of FDR, but were not enthused about much of the New Deal. The machine had seen some setbacks, not the least of which was the defeat of Senator Cameron Morrison in 1932. Morrison, a former governor, had been appointed to the Senate following the death of Senator Lee S. Overman. Morrison was challenged by Robert Rice Reynolds, a perennial candidate and virtually everyone thought the senator would win easily. Reynolds, a thoroughly engaging man, ran a highly unusual campaign. Morrison’s wife was extraordinarily wealthy and Reynolds shamelessly portrayed the senator as an out of touch and gluttonous rich man. Reynolds would gleefully read from the menu of the Mayflower Hotel where Senator Morrison lived in Washington, D. C. “Buncombe Bob” Reynolds would take his audience through an orgy of food choices, implying Morrison did little but eat breakfast, lunch and dinner at the elegant hotel.

To the surprise of almost everyone, Bob Reynolds upset Cameron Morrison in the primary and went on to easily win the general election.

Ralph McDonald campaigned fervently in 1936 against the sales tax and for the New Deal. McDonald loudly denounced the Shelby machine.

Clyde R. Hoey, despite his old fashioned appearance, was very well liked, an excellent speaker and was well known as a leading Methodist. McDonald did his best to paint Hoey as a creature of O. Max Gardner and as the former governor was Hoey’s brother-in-law, it was impossible for him to extricate himself. Hoey promised, if elected, to remove the sales tax from necessities, like food and medicine. Clyde R. Hoey also made a point to praise New Deal programs like Social Security and aid to farmers. Hoey scraped by McDonald in a run-off election.

Governor Hoey kept his word and worked closely with federal officials to get the most out of New Deal programs for North Carolina. The one exception was the Works Progress Administration (WPA); North Carolina was last in the nation in WPA spending.

Hoey was appalled when President Roosevelt proposed to expand the U. S. Supreme Court, but said little publicly. Governor Hoey was hardly excited at the prospect of Franklin Roosevelt seeking a third term as president in 1940. Hoey thought Secretary of State Cordell Hull should be nominated to run that year. Once again, he was relatively quiet about his objections, but his administration was that of a pro-business, conservative Democrat.

While serving as governor, Hoey left each day to trudge down the street to the drug store where he would enjoy a single Coca-Cola. Clyde R. Hoey’s political career might very well have ended after he left the governorship had it not been for his brother-in-law’s ailing health. O. Max Gardner had become an astonishingly successful attorney and was the leading candidate to oppose Senator Robert R. Reynolds in 1944.

Despite his high popularity following his initial election to the Senate, Reynolds became increasingly erratic, especially after being reelected in 1938. Reynolds was the most notable isolationist in the Southland. Most Southerners were noted for their strong internationalist views, but “Buncombe Bob” flirted with fascism and married Evelyn Walsh, the young daughter of the owner of the fabulous Hope Diamond. Reynolds had been married numerous times and by 1944 he was largely disgraced and discredited. Senator Reynolds wanted to run again, but thought better of it.

Max Gardner was poised to run for the Senate, but finally decided against it. At age sixty-seven, Clyde R. Hoey announced he was running for the United States Senate. Hoey remained popular and faced Congressman Cameron Morrison in the Democratic primary. Hoey easily defeated Morrison and North Carolina was then still a solidly Democratic state. The Republicans posed no real threat to Hoey’s election in the fall.

Being elected to the United States Senate was the crowning achievement of his political career and serving as a senator was a role Clyde R. Hoey relished.

At seventy-three, Hoey was reelected to a second term in the Senate. Until the last moment he fretted that former senator Bob Reynolds would try to reclaim his seat in the U.S. Senate. Reynolds was utterly unpredictable and his young wife had either died from an accidental overdose of sleeping pills or committed suicide. Reynolds was left with a small daughter; that child was quite wealthy through inheritance from what remained of one of the country’s great fortunes. Yet Bob Reynolds was at somewhat loose ends. He had built a home with a sweeping view of Asheville, but missed the prominence, prestige and attention of being a senator.

“Buncombe Bob” was seriously thinking about running again in 1950, but he finally concluded Hoey was too entrenched and popular. He opted to run in a special election for North Carolina’s other Senate seat. Reynolds gamely tried to campaign, but quickly realized he couldn’t win. He ran a poor third in the first primary. Senator Clyde Hoey was reelected without opposition.

Tall, gaunt, slightly stooped, Hoey’s was a familiar figure in post-world war Washington. Tour guides enjoyed pointing out Senator Hoey to visitors to the Capitol in his old-fashioned ties, frock coat, and high-topped shoes. Hoey was also easily recognizable from the fresh carnation he pinned to his lapel every day.

Despite his advancing years, Hoey earned something of a scandalous reputation amongst the female secretaries on Capitol Hill. Bobby Baker, who first came to the Senate as a thirteen year old page in 1943 and rose to become Secretary of the Senate, recalled in his oral history with the Senate Historian’s Office that many of the women were wary of encountering the courtly and apparently lecherous senator.

Hoey had the difficult and politically perilous task of heading a subcommittee charged with investigating the “five percenter” scandals during the administration of President Harry S. Truman. Senator Hoey was slowing down, but worked hard at his job. He returned to his suite in the Senate Office Building on May 13, 1954 and sat down at his desk, where he apparently suffered a stroke and died.

Senator Hoey was found by an aide, still seated at his desk, dead.

“He went the way he wished,” another aide said. That same aide recounted Hoey had said when death finally found him, he hoped it would come while he was still active.

Senator Hoey was taken home to North Carolina by his two sons and buried. After he had died, Margaret Chase Smith, the only woman serving in the U. S. Senate, quietly placed a lone carnation on Clyde Hoey’s empty desk inside the Senate Chamber.