Congressman Cordell Hull of Tennessee is frequently credited with being the “Father of the Income Tax.” Today, that is likely a dubious distinction. When the income tax was first approved in 1913, the tax code was fifteen pages long. Today, the tax code is more than 74,000 pages. Hull first came to Congress in 1906 after having been something of a local boy wonder. Cordell Hull had been Chairman of the Clay County Democratic Party when he was nineteen years old. At twenty-one, Hull was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives and later became a Circuit Court judge. Hull fought a difficult battle for the Democratic nomination for Congress in 1906 and while the vote count varies, he won by less than twenty votes.

Hull remained in Congress, representing the Fourth District, a hardscrabble group of counties in Middle Tennessee, which were religiously Democratic in their voting habits. The congressman represented an agrarian district and many of Hull’s constituents made their living as farmers. When he went to Washington, Cordell Hull was a bachelor and unlike some of his colleagues, the Tennessean cared little or nothing about social life in the nation’s Capitol. Hull tended to his district and intensely studied legislation he believed would help Tennessee and the country. Cordell Hull was quickly recognized as an expert on taxation and tariff issues. Prior to the passage of the income tax, the United States derived most of its income from tariffs and excise taxes, which disproportionally affected the middle and lower classes of the country. Tariffs placed taxes upon imported products, while excise taxes were placed on items like whiskey. Not surprisingly, tariffs were frequently unpopular with many Americans because they drove up the cost of many goods used by the average person or families.

When Cordell Hull first came to Congress, there was no income tax, nor was there any Social Security, few pensions for individuals, no organized health care, and no entitlement programs of any kind.

Hull’s “maiden speech” in Congress was on the subject of the income tax, which attracted little or no notice. Cordell Hull had a tendency to become obsessive about certain issues and the income tax was one of those. Hull recalled in his memoirs, “I must confess, I got nowhere with income tax in the Sixtieth Congress.” Hull related he talked about the topic in numerous speeches and “talked to any member of either House of Congress who was willing to listen to me.” Congressman Hull sadly remembered, “I talked to some Congressmen so often they were no longer willing to listen. I well recall that House leaders such as John Sharp Williams and Champ Clark, although strongly favoring an income tax, would turn and walk in another direction when they saw me approaching.”

Cordell Hull explained why he believed an income tax was necessary. “I have no disposition to tax wealth unnecessarily or unjustly, but I do believe that the wealth of the country should bear its just share of the burden of taxation and that it should not be permitted to shirk that duty. Anyone at all familiar with the legislative history of the nation must admit that the chief burdens of government have long been borne by those least able to bear them, while accumulated wealth has enjoyed the protection and other blessings of the Government and thus far escaped most of its accompanying burdens.”

Always persistent, Congressman Cordell Hull began to gather increasing support from other representatives from the Southern and Western states. As support for an income tax grew, opponents began to become concerned. Congress had once before approved an income tax, which was struck down by the United States Supreme Court in 1894 as unconstitutional. It was the opponents of the income tax who miscalculated when they proposed to sponsor a Constitutional amendment. The opponents figured by sponsoring a Constitutional amendment to establish an income tax, it would force Congressional proponents to drop their bid to enact an income tax legislatively. The opponents were confident it would be impossible for a Constitutional amendment to receive approval by three-fourths of the states.

The House Ways and Means Committee moved with alacrity in moving out the income tax proposal. In recommending passage by the full House, the Ways and Means Committee issued a statement noting, “Those citizens required to do so can well afford to devote a brief time during some one day in each year to the making out of a personal return…willingly and cheerfully.”

Not everyone shared the opinion of the House Ways and Means Committee. The richest man in America, John D. Rockefeller snapped, “When a man has accumulated a sum of money within the law…the people no longer have any right to share in the earnings resulting from the accumulation.”

Hull watched in wonder when the proposed Constitutional amendment sailed through the United States Senate on a vote of 77 – 0. It passed the House of Representatives by a margin of 318 – 14 in the summer of 1909. By 1913, three-quarters of the individual states had ratified the amendment and the income tax was a fact. “Here at last,” Hull exulted, “was fruition to my work and study of twenty years.”

Forty-two stated ratified the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution, with only six states rejecting it.

Virginia was one of those states that refused to ratify the Constitutional amendment for an income tax. Richard E. Byrd, Speaker of Virginia’s House of Delegates, spoke passionately against ratification. “A hand from Washington will be stretched out and placed upon every man’s business, the eye of the federal inspector will be in every man’s counting house,” Byrd thundered. “The law will of necessity have inquisitional features, it will provide penalties, it will create complicated machinery. Under it men will be haled into courts distant from their homes. Heavy fines imposed by distant and unfamiliar tribunals will constantly menace the tax payer. An army of federal inspectors, spies, and detectives will descend upon the state.”

Few, if any, members of Congress lost their seats for having supported an income tax, chiefly because so few people paid it. The tax rate was 1% on income over $3,000 for a single person and over $4,000 for a married person. For those lucky individuals earning over $500,000 per year, the income tax rate was 6%. The average amount paid by Americans in income taxes was $97.88. The average American worker earned around $800 annually. Only 4% of Americans made more than $3,000 per year. John D. Rockefeller paid an estimated $2 million the first year the income tax was collected. One taxpayer wrote the Bureau of Internal Revenue to say, “I have purposely left out some deductions I could claim, in order to have the privilege and the pleasure of paying at least a small income tax…”

The income tax rates did not remain at that low level for long. The United States entered World War I in 1917 and immediately needed cash for preparations. The United States had a budget of $1 billion in 1916; by the end of the war in 1919, the budget had grown to $19 billion. The size of the Internal Revenue Service grew along with the tax rates. The IRS employed 4,000 workers in 1913; by 1919 it employed some 21,000 workers. The tax rate for those rare individuals earning more than $1 million annually was 77%. Tax revenue did increase dramatically. Total tax revenue collected by the United States government went from $344 million to $5.4 billion. The percentage of revenue derived from income taxes went from 10% to 73%.

Originally, the income tax was promoted to be temporary and many rightly worried it would become permanent. The effect was immediate with revenue from taxes growing from $21 million in 1910 to $34.8 million in 1912. America’s businessmen paid almost 90% of those income taxes paid into the U. S. treasury.

From 1913 – 1921, the Democrats had held both the White House and the Congress. In 1918, the Democrats suffered defeat in the midterm elections, which, along with his serious illness, hampered the administration of President Woodrow Wilson. Champ Clark was replaced as Speaker of the House by Frederick Gillett of Massachusetts, despite the plea of President Wilson, who warned the electorate he would consider the election of a Republican Congress a repudiation of his administration. The 1918-midterm elections foretold a change of administrations in 1920. The Republicans elected three presidents during the decade of the 1920s and the income tax rate was cut, although it never went back to the low rates of 1913.

Herbert Hoover, a Republican, occupied the White House when the Great Depression hit America. Many Americans could not afford to pay any kind of tax and those lucky enough to earn approximately $16,000 paid about $1,000 in income taxes. To give readers an idea of just how much buying power $16,000 had in 1929, it would be the equivalent of more than $224,000 in today’s dollars.

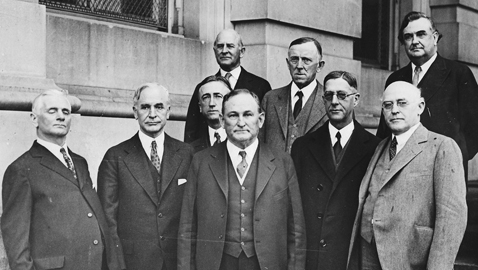

Nor did his advocacy of an income tax affect Cordell Hull’s political fortunes. Although he lost his Congressional seat in the 1920 Republican landslide, he was reelected easily in 1922 when he faced his GOP successor. Hull was never again seriously challenged inside Tennessee’s Fourth Congressional district and in 1930 he was elected to the United States Senate. Once in the Senate, Hull was assigned to the Senate’s Finance Committee in recognition of his fiscal expertise and interests. Hull did not remain long in the Senate, selected by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to serve as Secretary of State. Cordell Hull became the longest serving Secretary of State in our country’s history. Hull had few peers throughout American history for the admiration and respect he won from his fellow countrymen.

Hull was still serving as Secretary of State when the income tax rates jumped sharply, yet again because of war. In 1939, before the advent of World War II, there were roughly 6.5 million Americans paying the income tax; collectively, those folks paid about $1 billion annually. By the end of World War II, some 48 million Americans were paying income taxes and annual revenues averaged around $19 billion. Once again, the IRS grew along with the tax rates and revenue. The IRS employed some 27,000 workers in 1941 and 50,000 in 1945 when World War II ended.

The Chicago Tribune summed up the difference in the lives of Americans, noting the war had changed the income tax “from a class tax to a mass tax.”