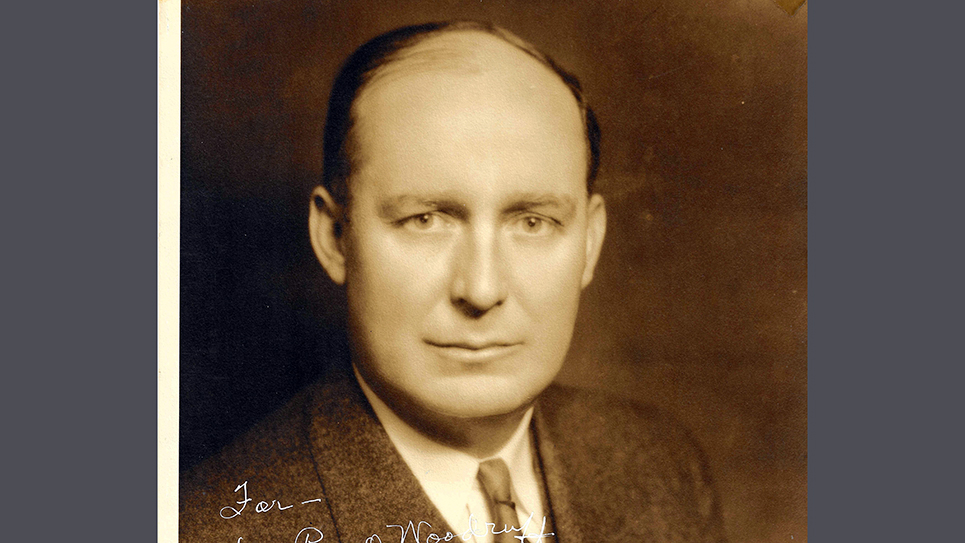

During the eighty-one years that comprised the life of Dewey Jackson Short, folks knew he was here. Short was a true son of the hill country of the Ozarks and a gifted speaker who could hold his audiences spellbound, sometimes referred to as the “Hillbilly Demosthenes.” As to Short’s speaking ability, no less than Richard Nixon wrote in his book of political memoirs,” In the Arena,” that Dewey Short was likely the best orator he had ever heard speak.

Dewey Short could mix his background as a theologian with his politics. “I look at the Supreme Court and I know why Jesus wept,” Short once said tartly of Franklin Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson founded the Democratic Party and President Roosevelt has dumbfounded it.” No yokel rube, Dewey Short had studied for a year at Oxford in England and had earned a law degree from Harvard.

Carl Vinson, one of the longest-serving members of the House of Representatives in our history, served for decades on the Armed Services Committee with Dewey Short and once said the Missourian was “the most beloved man I have ever known.” Yet Dewey Short could not be called mild in any way; Short was a staunch conservative and a partisan.

Short once said of his childhood, “It was root hog or die. With 10 kids in the family, we licked the platter clean. I went barefooted, bareheaded, shined shoes, delivered newspapers, raised and fed pigs and drove a team of jennies.

“By the time I was ready to go to Marionville College, I had saved $1,000. That was a lot of money then, and it took me through two years of college.”

Dewey Short was a devoutly religious man and when first asked to consider running for Congress was reluctant. He was content to remain a theologian until a trip to Washington, D.C., changed his mind. Standing in the Rotunda of the Capitol Building, an awed Dewey Short soaked in the sight of the worn marble, the statues of famous Americans, the living history of his country. Dewey Short never lost his feeling of awe while being in the Capitol Building and it was likely one of the reasons why he chose to retire in Washington, D.C., rather than go home to Missouri. The former congressman liked to go back to the Capitol every so often to wander the halls and visit with old friends. It was his silver-tongued oratory which launched his long career in Congress. In 1927, Short was asked to be the speaker at the Lincoln Day Dinner at the Shrine Mosque in Springfield. Dewey Short’s speech so impressed local Republican leaders they asked him to run for Congress.

Short’s father, Jackson Short, was better known as “Uncle Jack” to many folks locally. “Uncle Jack” Short was a power in the local Republican Party. Such was the elder Short’s influence that some joked, “Uncle Jack not only told his flock how to vote, but he told them what to wear and what to eat.” It was “Uncle Jack” who had first launched his son into politics.

1928 was a big Republican year nationally and in Missouri as well. Dewey Short was elected to Congress to represent much of the “bootheel” of Missouri. The Great Depression changed politics and the majority Republican Party suffered politically. Dewey Short lost the 1930 election to Democrat James Fulbright, who had been the congressman Short had beaten to win election to the House of Representatives in 1928. Fulbright won, albeit narrowly. Rather than try and reclaim his seat in Congress, Dewey Short sought to win a seat in the United States Senate in 1932. Short lost the GOP primary to Henry W. Kiel, who was the former mayor of St. Louis. Short later described his decision to run for the Senate as “foolish” and noted 1932 was a terrible year for Republicans and the party didn’t succeed in even electing a dogcatcher.

Redistricting had altered Missouri’s Seventh Congressional District and Short decided to run once more. Dewey Short faced a serious opponent for the GOP nomination for Congress in Joe J. Manlove, who had served ten years before losing his seat in the 1932 election. Short won a solid, albeit narrow victory in the primary and claimed the right to face incumbent Democratic congressman Frank H. Lee in the general election.

Dewey Short campaigned hard during the fall, visiting the numerous cities, towns and hamlets that comprised Missouri’s Seventh Congressional District. A district composed of fifteen counties, the former congressman carried ten of them in November, beating Frank Lee with roughly 53% of the ballots cast. Congressman Short repeated the feat in 1936, which was a banner year for Democrats nationally. For the next two decades, Dewey Short remained unbeatable inside his own congressional district.

As the decade of the 1950s dawned, Congressman Dewey Short’s percentages began to dwindle, always a warning sign for an incumbent. Short drew a credible challenger inside the Republican primary in 1954 in State Senator Noel Cox. Cox was young and quite ambitious and was a veteran of ten years in the Missouri State Senate. Even Congressman Short readily acknowledged Cox was a tough opponent and was slow to kick off his reelection campaign because his responsibilities kept him in Washington, D. C., longer than usual.

“The Goliath of Galena” reminded folks, “. . .you’ve got to learn to be a congressman and the most valuable asset I can have is 22 years experience there.” The forty-three-year-old challenger scoffed at the promise of Dewey Short’s years in Congress being used for the advantage of the people of Missouri’s Seventh Congressional District were “gone forever and lie smothered in the bottom of a heap of promises to a chosen few both in politics and in industry.” Cox reminded primary voters Dewey Short had returned to Congress by defeating another former congressman, Joe Manlove, whom Short had said had been in Congress too long. “Joe Manlove, the man he defeated, had been in Congress only 10 years – – – not 22 years,” Noel Cox cried.

Incumbents always tout their experience and seniority, which equates to influence and the ability to get things done for their people. Challengers necessarily campaign against incumbents by assaulting the notion of seniority and placing the blame for whatever ails the country at the feet of the person holding office. Noel Cox was no exception and he battered Dewey Short’s record in Congress. Well financed, Cox managed to carry only three counties out of seventeen, but he did hold Short to 58% of the vote.

One reason for the change in the voting habits of Missouri’s Seventh Congressional District was due to redistricting and the inclusion of Greene County (Springfield), which made it more Democratic. 1954 saw Congressman Dewey Short face Democrat J. M. Lowry in the general election. Lowry only carried two of the seventeen counties constituting Missouri’s Seventh Congressional District, but the Democrat held Short to less than 54% of the vote. Considering that the Republicans had won control of the House of Representatives in the 1952 election, which elevated Short to the chairman of the powerful Armed Services Committee, it was a weak showing. Concentrating upon his increased duties in Washington, D.C., some of the home folks may well have felt ignored. Only the most adroit officeholders are able to balance keeping in touch with the people back home and accruing real influence in Washington.

Democrats felt Congressman Short might be vulnerable to a serious challenger and nominated Charles Harrison Brown, better known as “Charlie” in 1956. A radio announcer at the age of sixteen, Brown was quite an orator in his own right. A champion debater in high school, Brown had won a national oratorical contest. Charlie Brown continued honing his debating skills and college and earned a reputation as a fellow who could think fast on his feet, always a plus in politics. It was Brown’s gift of gab that caused Missouri’s U.S. Senator Tom Hennings to suggest he run for Congress.

Congressman Short referred to his opponent during the 1956 campaign as “Little Charlie,” while the challenger reminded voters at age thirty-six, he was six years older than Short had been when the folks had sent him to Congress for the first time in 1928.

Charlie Brown only carried five of the seventeen counties in Missouri’s Seventh Congressional District. While keeping track of the ballots trickling in, Congressman Dewey Short was trailing and told friends “it looks like it’s all over.”

The final count was paper-thin and the election rested upon the count of the absentee ballots in the congressional race, but the Democratic candidate won the general election by eking out a victory by exactly 1,060 votes. Dewey Short’s twenty-six years in the House of Representatives had come to an end.

Asked about his defeat, the congressman acknowledged, “Charlie ran much better than I thought he would. I expected Jasper, Newton and Lawrence counties to come in more for me.” Ultimately, Dewey Short told a reporter, “It’s hard to beat five years of drought, a lot of money and a good campaigner.” The congressman believed “our total lack of organization on the state level hurt me.”

“I learned to win without crowing and to lose without crabbing,” Congressman Short said philosophically. “I can take it. There’s no bitterness in my heart. I am grateful to all my friends.”

Asked what he would do after his service in the House of Representatives was done, the congressman replied, “I’ll take a long rest – – – perhaps I’ll live longer now – – – and catch up on my fishing.”

Charlie Brown was less gracious than Dewey Short was in defeat. Brown modestly termed his victory “a miracle” and attributed his win to the “case of a man who has grown tired and negligent” as well as unhappy farmers who were disgruntled and formed a large bloc of voters in the largely rural district.

Throughout his long political career, Dewey Short had retained his ties to the Ozarks and always carried with him a seeming reminder of the hills and hollows of his home. By way of contrast, one newspaper reporter wrote of Charlie Brown, “He’s a small-town boy who became the equivalent of a Madison Avenue huckster. . .”

Dewey Short was not out of public life for long after leaving the halls of Congress, as President Eisenhower appointed the former congressman as Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil–Military Affairs. Short held that post for just over a year before retiring.

Dewey Short remained in Washington, D.C., following his retirement. His last visit to his home was during the summer of 1979 when he was to be inducted into the Ozarks Hall of Fame at the School of the Ozarks. Out of the House of Representatives for almost a quarter of a century, Short was a revelation for the generation who grew up without knowing of his time in the House. The former congressman although physically depleted by old age and time, once again demonstrated his ability to hold an audience spellbound, which he did for an hour and thirty-five minutes.

Dewey Short died at his home in Washington, D.C., a few months after coming home to Missouri. Short’s final journey home to the Ozarks was to be buried in his hometown of Galena. Family and close friends gathered at the home the former congressman still owned there. A crowd of some two hundred people, hardly the number that would have attended his funeral had he died at the peak of his popularity, attended the services across the street from the Short home at the Galena Community Church.

Dewey Short had once told a reporter, “I was born to Jackson Grant Short and Permelia Cordelia Long across the street in Galena from where we live, and, when I die, I will be buried on the hill with the rest of my people.

“Galena will always be home,” he said softly.

And so it was.