Many of our fellow Tennesseans are positively football crazy; most of us remember University of Tennessee quarterback Heath Shuler was elected to Congress from North Carolina. Yet there is hardly any person in the State of Tennessee with better name recognition than the person who happens to be the head coach of the UT Vols. The lure of politics has seduced some football coaches in other states; Bud Wilkinson of Oklahoma was the winningest coach in Sooner State history when he announced he was running in a 1964 special election to fill the Senate seat of Senator Robert S. Kerr, who had died in office. Wilkinson only narrowly lost that election. There is a football coach sitting in the United States Senate now: Tommy Tuberville of Alabama. Not surprisingly, athletes who have played sports have been more politically successful than those who have coached them. Oklahoma has been especially fertile political ground for former football stars; J. C. Watts was elected to Congress, as was Hall of Fame wide receiver Steve Largent. Jim Bunning, who was a baseball pitcher for 17 seasons, was elected to Congress and the United States Senate from Kentucky. Jack Kemp was the quarterback for the Buffalo Bills and had just retired when he was elected to the House of Representatives from Buffalo, New York. Kemp became a national figure in Congress and was Bob Dole’s vice-presidential running mate in the 1996 election. Bill Bradley of New Jersey played basketball for the New York Knicks before being elected to the United States Senate. Gerald Ford was a star linebacker for Michigan before beating incumbent Congressman Bartel Jonkman in the 1948 GOP primary.

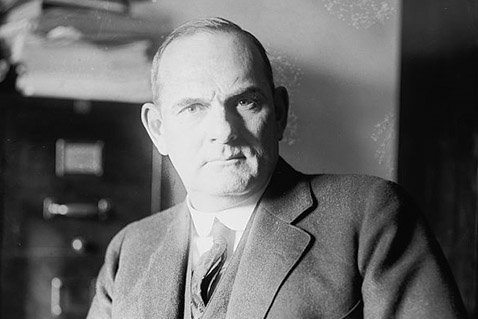

Very few people recall Hubert Fisher of Memphis, but to my knowledge, he is the only person ever to serve as head football coach of the University of Tennessee Volunteers who was elected to Congress. Fisher was an athlete who prized beauty and raised and cultivated flowers. Hubert Fisher served as the congressman from Memphis and Shelby County from 1917 until his retirement in 1930.

Hubert Fisher had been a star football player and had attended the University of Mississippi before going to Princeton where he obtained a Master of Arts degree. It was at Princeton where Fisher was hailed for his prowess on the football field. For two years, Hubert Fisher was the head football coach at the University of Tennessee.

Likewise, it was at Princeton University where Hubert Fisher made an enduring friendship with one of his professors, Woodrow Wilson. Fisher went to Memphis in 1904 where he made his home and was hired by the law firm of Carroll & McKellar. That firm was one of the busiest in Memphis and the senior partners were Colonel William Carroll, a former United States senator, and Kenneth D. McKellar, a future congressman and senator. After McKellar’s election to the House of Representatives, the firm’s name was changed to Carroll, Scott & Fisher.

Hubert Fisher was a delegate to the 1912 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore that nominated Woodrow Wilson as its presidential candidate. Fisher’s friendships with Wilson and McKellar proved to be helpful when he was appointed U. S. Attorney for the Western District of Tennessee. Fisher was nominated for the post by President Woodrow Wilson and had the enthusiastic backing of Congressman K. D. McKellar.

Senator John Knight Shields controlled the federal patronage for West Tennessee at the time and he was opposed to Fisher’s appointment. When Shields refused to budge, an angry and exasperated President Wilson nominated Fisher over the senator’s objections. McKellar later recalled Hubert Fisher supported Shields for reelection in 1918 although he disliked and refused to personally speak to the senator.

McKellar became a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate, facing two titans of Tennessee politics inside the primary. The incumbent was Colonel Luke Lea, the youngest man ever to be elected to the United States Senate from the Volunteer State. Lea owned the Nashville Tennessean and ruthlessly used his newspaper to promote himself and verbally lash his opponents daily. The other contestant was former Governor Malcolm Rice Patterson. Both Lea and Patterson were highly polarizing figures inside the Democratic Party in Tennessee. Lea seemed unable to keep himself from meddling in state politics and displayed far more interest in what was occurring in Tennessee than tending to his duties in Washington. Patterson had virtually destroyed his own political career after he had run a close race for the governorship with former U.S. Senator Edward Ward Carmack. An editor by trade, Carmack was almost as fiery an orator as he was facile with his pen which seemed to be dipped in vitriol. Patterson was a forthright “wet”, meaning he was opposed to the prohibition of liquor and alcoholic beverages, while Carmack was the champion of the “drys” in Tennessee. Carmack was killed in a gun battle on the streets of Nashville with Colonel Duncan B. Cooper and Cooper’s son Robin. Patterson promptly pardoned Colonel Cooper, which caused a fierce outcry throughout the state. That is when the imposing statue of Carmack was placed in front of the Tennessee Capitol. Patterson’s bid for the United States Senate was his determined effort to make a political comeback. Lea’s opponents inside the Democratic Party, led by Congressman Cordell Hull, had moved up the Democratic primary to 1915, fully a year before the 1916 general election. It was the first time the people of Tennessee would choose their senator by popular election. McKellar campaigned as the “harmony” candidate and there were thousands of Democrats in Tennessee who believed either Patterson or Lea very well might lose to a Republican in the general election. McKellar led the first election and won the run-off primary in December; it is the only time in Tennessee’s history a political party in the Volunteer State had a run-off election to determine the party’s nominee.

With McKellar the Democratic nominee for the United States Senate in 1916, Hubert Fisher became the candidate of his party to replace K. D. McKellar in the House of Representatives. Fisher was easily nominated and elected. Once in the House, Fisher became a member of the Military Affairs Committee where he looked after the interests of Tennessee in general and the people of Shelby County in particular. When federal judge Harry B. Anderson, a Republican appointed to the bench by President Calvin Coolidge, was accused of misdeeds by Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia (future mayor of New York and a Republican), Fisher made a speech on the House floor defending the judge.

Fisher was married to Louise Sanford of Knoxville and brother-in-law to her brothers, including Edward Terry Sanford, who became a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Fisher likely deserves much of the credit for President Warren Harding nominating Edward T. Sanford for the high court as he implored Senator McKellar to do all he could to help his Republican brother-in-law. It was McKellar who approached the frosty Republican leader of the United States Senate, Henry Cabot Lodge.

McKellar, knowing of Lodge’s devotion to his alma mater, Harvard University, casually mentioned Judge Sanford’s being a “Harvard man.” That opened doors for the judge’s nomination and confirmation to the Supreme Court.

As a member of the House and the Tennessee delegation, Hubert Fisher was a strong advocate of the government operation of Muscle Shoals, the forerunner of the TVA.

Fisher seemed content to remain in Congress, although his hearing had deteriorated over the years. There had been rumors the congressman’s relationship with Edward Hull Crump had also been deteriorating as well. Still, Congressman Fisher was stunned with the sudden announcement on June 9, 1930, that Crump had declared his own candidacy for the Democratic nomination for Congress from Shelby County. Fisher had been expected to file his own papers the following day. In the face of Crump’s announcement, Hubert Fisher did the only practical thing he could do: he announced he would retire from Congress. E. H. Crump by that time had firmly established the political machine inside Shelby County that made his mastery of the political and social life of his domain complete. Even Senator McKellar was caught off guard by Crump’s announcement he would run for Congress. Although the senator discounted the notion he and Crump had fallen out, McKellar was irritated and horrified by the Memphis Boss’s rough treatment of his friend Hubert Fisher. As congressman, Fisher had chosen to remain somewhat aloof from the Crump organization and that likely helped to terminate his career in the House of Representatives. According to the Tennessean, Crump had indicated he would back Fisher for one more term if the congressman agreed to step aside in 1932. Fisher reportedly replied he wanted two more terms in the House. Crump had been beleaguered by several of his lieutenants who desperately wanted Fisher’s seat in Congress. The Boss ultimately decided the only way to keep his machine united was for him to run himself.

Fisher may well have derived some quiet pleasure in Crump’s unhappiness in Congress. Crump, used to being the biggest fish in the ocean in his own Shelby County, found himself one of a number of freshmen congressmen and one of 435 representatives in the House. The real power in Washington, D. C. inside the Tennessee delegation was Senator McKellar. Crump quickly realized he did not have the prestige or influence of McKellar in the Nation’s Capitol. Nor did the Memphis Boss like being away from his wife and three sons or his extensive business interests. After serving two terms in the House, E. H. Crump announced he was coming home to Memphis and selected Walter Chandler as his successor.

For his own part, Congressman Fisher never expressed the slightest bitterness at Crump or his being shoved out of Congress. Fisher’s own announcement he would voluntarily retire at the conclusion of his term was gracious and the congressman said he would be happy to live amongst his flowers.

There is every reason to believe Hubert Fisher was content in retirement. The Memphis Commercial Appeal announced Fisher was to be the speaker at the home of Mrs. Thomas Semmes for the Memphis Garden Club on Thursday, April 17, 1941. Mrs. J. P. Norfleet, president of the Horticultural Club of Memphis, had planned the program and introduced the former congressman. Fisher was to give “helpful advice” and “offer suggestions” to his listeners on the use of “new materials in Spring planting.”

Months later, Hubert Frederick Fisher was discovered dead in New York City. Authorities discovered the body of a man the evening of June 17, 1941, at Thirty-sixth Street and Fifth Avenue. The next day the body was identified as Hubert F. Fisher of Germantown, Tennessee. The sixty-three-year-old Tennessean was identified by his twenty-seven-year-old son Adrian, who had come from Arlington, Virginia to New York after a card bearing the former congressman’s name had been found in the dead man’s clothing. Adrian Fisher explained his father had gone into the nursery business following his retirement from Congress and had gone to New Jersey to visit friends and had been staying at the William Sloane House in New York City to attend a reunion of classmates from Princeton University. Fisher had left Memphis on Thursday, June 12, 1941, for New York.

The former congressman’s death came as a shock to his family and friends as he had been in apparent good health, aside from his continuing deafness. Adrian Fisher had the sad duty of sending his father’s remains back home to Tennessee. Adrian worked for the State Department in Washington, D. C. Death had come from a heart attack. In death, Hubert F. Fisher had one last tie to Knoxville. The former congressman was buried in Old Gray Cemetery in the Sanford plot of his wife’s family. Fisher sleeps there to this day.