By Ray Hill

Named for the four-time presidential candidate and Kentucky statesman Henry Clay, H. Clay Evans was a highly important figure in Tennessee’s Republican Party. Evans had a storied and diverse career, a successful businessman who manufactured freight cars for railroads, he served a term in Congress, was the mayor of Chattanooga, organized the public school system in Chattanooga, and was elected governor of Tennessee on the returns. Unfortunately, the majority Democrats threw out enough votes to give the election to Governor Peter Turney.

Evans was also recognized nationally, having served as Commissioner of Pensions in the administration of President William McKinley. Evans was the American General Consul in London under President Theodore Roosevelt. H. Clay Evans was also the leader of Tennessee’s Republican Party and one of the leading GOP figures in the South.

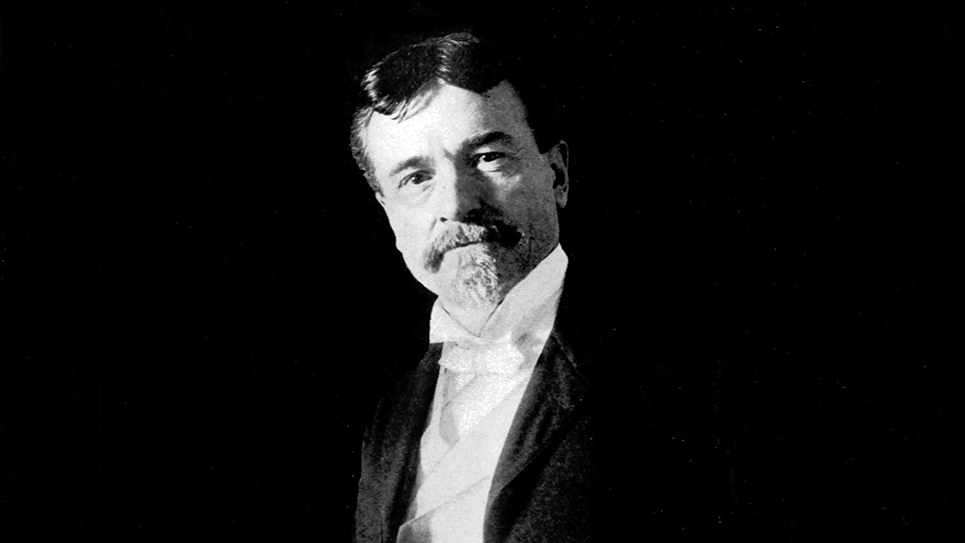

The first thing one noticed about Henry Clay Evans was his appearance, which was striking. Today, Evans would look precisely like Hollywood’s version of the Southern “colonel.” The Nashville Banner stated Evans “had the knack of making and retaining friends in all classes of society.” While H. Clay Evans carried the reputation of a great man, “his intimates knew him as a lovable character” whose “kindly heart” always answered “every appeal.” While a leader in public affairs, Evans was known for his “genial and considerate and self-effacing” attitude in private. The Chattanooga News remembered H. Clay Evans as a “man of magnetic and attractive personality and strong individuality” whose “positive views” made him a natural for public life.

Evans was born in Pennsylvania and moved with his family to Wisconsin as a boy. Like most other young men of his time, he enlisted to fight in the Civil War. For a brief time, he was in Chattanooga with the quartermaster’s department before wandering off to Texas where he helped in rebuilding the Army post in Brownsville and later to New York. Likely the reason for his travels to New York was a young lady named Adelaide Durand. The two were married in Westfield, New York, in 1869. Their marriage produced three children.

In 1870, H. Clay Evans moved his family to Chattanooga, which was to be his home for the remainder of his life. There he began his business of manufacturing freight cars at a time when virtually all American commerce was carried by railroad or water. Evans quickly became one of Chattanooga’s leading citizens and was elected mayor in 1881. H. Clay Evans served two terms as Chattanooga’s mayor and was later Chattanooga’s first school commissioner. Eventually, Evans founded the Bromley & Evans Car Wheel Foundry Company, which flourished.

By 1888, H. Clay Evans was contending for the Republican nomination for Congress from Tennessee’s Third District. Evans was contesting the nomination of his party with H. M. Wiltse and the candidate was to be decided in a convention rather than a primary election. Evans was duly nominated by a delegate from Bradley County and his nomination was seconded by a number of orators, including Parsons Houston, a Black delegate who proclaimed Evans the friend of both the poor and African-Americans inside Tennessee’s Third District. It was an age when oratory and the ability to make a moving speech were highly appreciated and valued. One delegate from Grundy County gave a sample of an oratorical flourish when he bellowed, “I arise to second the nomination of that matchless name; the name at whose sound democracy (meaning the Democratic Party) trembles – – – the Hon. H. Clay Evans.”

Martin of Hamilton County offered his own speech which rivaled that of his friend from Grundy. “I desire to put into nomination a man who has always been a Republican; who never knew what it was to scratch a ticket; a man of princely parts; a man who is the friend of the workingmen, and who has never failed a friend in the hour of an emergency. I allude to the Hon. Henry M. Wiltse.”

As the roll was called and county delegations cast their ballots, it became obvious H. Clay Evans was the choice of the convention. S. H. Martin who had put Wiltse’s name into nomination arose and asked for recognition by the chair, which was granted. Saying he was a friend of Mr. Wiltse “and out of deference to what I believe is the majority will of this convention, I desire to withdraw his name from before this convention.” Martin’s statement was greeted by thunderous applause from his fellow delegates. Evans received more than 233 votes to 29 for Henry Wiltse.

The Chattanoogan rose to thank the delegates for making him their GOP nominee to run in the general election. He had run for Congress once before in 1884 and Evans told the delegates, “Four years ago you did me the honor to nominate me. I did not have ten acquaintances outside of Chattanooga in this district.” That first congressional campaign, although lost, provided Evans with a host of friends outside his own community. Evans promised, “And I am going to make the race to win.” The Republicans roared their approval in reply.

Evans briefly recounted the election four years earlier when Grover Cleveland had reclaimed the White House for the Democratic Party. H. Clay Evans noted the Democrats had made good on providing good government “for a year and a half” or so. “Business was revived and we had prosperity all over the country. We enjoyed such a boom as this country has not seen before,” Evans told his fellow Republicans. After a brief pause, he added, “But the Democratic Party cannot stand prosperity.” As a result, according to H. Clay Evans, the Democrats had “set about to end the boom and bring about hard times.” Evans blamed the bust on President Cleveland and the Democratic Party’s free trade policies.

The incumbent congressman was John Randolph Neal, father of the famed law professor and perennial candidate of the same name. Congressman Neal was not seeking reelection due to ill health despite being a relatively young man. The Democrats had nominated in place of Congressman Neal forty-year-old Creed Fulton Bates. An attorney, Bates enjoyed a lucrative law practice and was known for having an “almost heroic build” and sunny disposition.

The campaign for Tennessee’s Third Congressional District ended with a massive political event in Chattanooga, the home city of both candidates. Evans and Bates had been making a joint canvass of the district and each spoke at a gathering that night, with both the GOP and Democratic candidates speaking for an hour. Evans spoke first and his partisans applauded, yelled and bellowed their approval as he took his seat while Colonel Bates was introduced by a supporter. The campaign ended with passions running high on both sides.

The Chattanooga Daily Times heralded “It’s Bates” yet reported Democrats had suffered “a Waterloo defeat” for its own ticket inside the City of Chattanooga. Chattanoogans turned out in record numbers and posted the largest vote ever recorded in the city previously. H. Clay Evans polled 4,248 votes to 2,428 for Creed Bates, a majority of 1,820. Evans also carried Hamilton County, winning with a 315-vote majority outside the city limits. The day after the election not all the votes had been counted and Republicans confidently expected Evans’ majority in Hamilton County to grow.

The Daily Times reported after “a calm and conservative study of the figures” it had concluded Colonel Creed F. Bates had been elected to Congress. According to the Daily Times, Bates had carried Grundy, Meigs, Monroe, Polk, Sequatchie, Van Buren, Warren, and White counties, while Evans had prevailed in Bledsoe, Bradley, Cumberland, Hamilton, James, Marion, McMinn and Rhea. Each candidate won eight of the sixteen counties comprising Tennessee’s Third Congressional District.

For those readers wondering about James County, it was created out of parts of Hamilton and Bradley counties by an act of the Tennessee General Assembly in 1871. The county went bankrupt and its residents voted to become part of Hamilton County in 1919.

A day later, the Chattanooga Daily Times reported the Democrats had conceded the congressional race and H. Clay Evans had been elected by about 200 votes. Republicans celebrated the election of Evans with a parade, bonfires, and fireworks.

Clay Evans only served two years in Congress as Democrats conspired to alter his district successfully, leading to the election of Henry Clay Snodgrass in 1890. Much of the reason for Democrats having gerrymandered Evans out of the House of Representatives was his support for the legislation sponsored by Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts. The Lodge Bill was popularly known by its supporters as the Federal Elections Bill. Among its opponents, especially in the Southland, it was referred to as the Lodge Force Bill. The purpose of the bill was to protect the integrity of elections for the U. S. House of Representatives. Much of the bill’s purpose was to allow Blacks, which were then mostly Republicans, to vote in the South. The Lodge Bill had passed by only six votes in the House and one of those had been the vote of Congressman H. Clay Evans.

Following his defeat by Henry Snodgrass, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Evans as an Assistant Postmaster General.

In 1894 H. Clay Evans became a candidate for governor against incumbent Peter Turney.

Turney, a ponderous and portly man, balding with a beard, had been Chief Justice of Tennessee’s State Supreme Court when he had first been elected governor in 1892. A plurality of the vote had elected Turney in 1892 as incumbent John Buchanan ran in the general election as an Independent after it became increasingly clear he could not win renomination as a Democrat. With four candidates running in the general election, Peter Turney won with a plurality of the ballots cast.

Governor Turney’s administration was beset by several nagging issues which helped to continually diminish his personal popularity with Tennesseans. The country was also plagued by an economic depression in 1893 referred to as the “Panic of 1893.” The depression had a profound effect on every segment of the American economy and caused something of a political realignment in much of the country. It also affected the political fortunes of Governor Peter Turney in Tennessee.

The Memphis Commercial Appeal reported what had once been “a little whisper” that H. Clay Evans would be a candidate for the GOP nomination for governor had “become a real loud sound” the week before Republicans met in the convention. When Republicans did gather together to choose their gubernatorial nominee, a headline in the Chattanooga Daily Times read, “The Republicans Name Their Lamb for the Slaughter Today.”

Evidently, the Republican state convention was a lively and colorful affair. One delegate drew a pistol and the Knoxville Journal and Tribune primly reported some delegates had indulged “in the language of the bar room.” According to the Republican Leader, which was published in Knoxville, John E. McCall placed in nomination the name of H. Clay Evans. McCall said conditions in Tennessee were so gloomy only a candidate like Evans could possibly have a chance of winning the general election. McCall cried only H. Clay Evans could put Governor Peter Turney in his political grave.

Evans was duly nominated at the state convention, a choice that was quickly applauded by the Knoxville Journal and Tribune, which called the selection of the former congressman “wise.” H. Clay Evans would not only make a good governor and provide Tennesseans with honest government but the Journal and Tribune assured its readers he was a man of high character, “an able man, a clean man, a pure man, a patriot, a useful and valuable citizen.” H. Clay Evans was in fact the kind of man other men could vote for “without having to apologize to their own consciences or to their wives and daughters.” Needless to say, the Knoxville Journal and Tribune was for H. Clay Evans for governor of Tennessee.