Virtually anything can happen in politics. The fight for one man, one vote had finally brought about a change in reapportionment, giving urban counties more representation, since districts were drawn according to population. The rural domination of Tennessee’s legislature was over. Still, the rural bloc in the legislature would remain a potent force, largely because those legislators tended to stay in office, accrue seniority and many of them made themselves experts on parliamentary procedure. Urban legislators, for the most part, tended not to serve as long and did not bother to acquaint themselves with the rules.

With reapportionment, political change came with more Republicans being elected to the state legislature. As the 1969 session of the Tennessee House of Representatives opened, a great deal of attention was focused upon a seventy-three-year-old freshman legislator from West Point, Tennessee. West Point is a hamlet in Lawrence County with a population of 151 people. It is the 439th most populated city in the State of Tennessee out of 499 municipalities. The 1968 election saw Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey running for the presidency, along with Governor George Wallace of Alabama seeking election as president as a third-party candidate. Richard Nixon had carried Tennessee in 1960 against John F. Kennedy and had been on the GOP ticket when Dwight D. Eisenhower had carried the Volunteer State in 1952 and 1956. Nixon carried Tennessee once again in 1968. The surprise was Humphrey ran a poor third with Governor Wallace carrying much of West Tennessee. Four Republican congressmen, Jimmy Quillen, John Duncan, Bill Brock and Dan Kuykendall, were all reelected. So were Democrats Joe L. Evins, Dick Fulton, Robert “Fats” Everett, Bill Anderson and Ray Blanton.

While every election brings along a surprise in an outcome, most observers were shocked when the state legislature appeared to be literally split down the middle. Republicans had won their greatest legislative victory in Tennessee’s history up to that point, winning 49 seats. The Democrats also had won 49 seats and immediately people began speculating the balance of power was held by J. P. Kimbrell, who had been elected to office as an Independent.

One ultra-ambitious freshman legislator, Charles Howell III of Nashville, announced his candidacy for Speaker of the House almost before all the votes had been counted. Should Kimbrell vote with the Republicans to organize the House, it would be the first time since Reconstruction the GOP had enjoyed a majority in the lower chamber. Tennessee had not elected a Republican governor since Alf Taylor in 1920 and Democrat incumbent Buford Ellington faced the possibility of shuffling his legislative program to one which could get the necessary votes from a chamber dominated by the other party.

Howell eagerly told a reporter for the Nashville Tennessean, “I have been in touch with Mr. (J. P.) Kimbrell of Lawrence County and he has indicated to me that there is a possibility he may join us in organizing the House of Representatives.” As to his own candidacy for the speakership, Howell modestly said, “This may seem a presumptuous honor for a freshman legislator to aspire to, but I think I have broken some precedents before and I want to try again.”

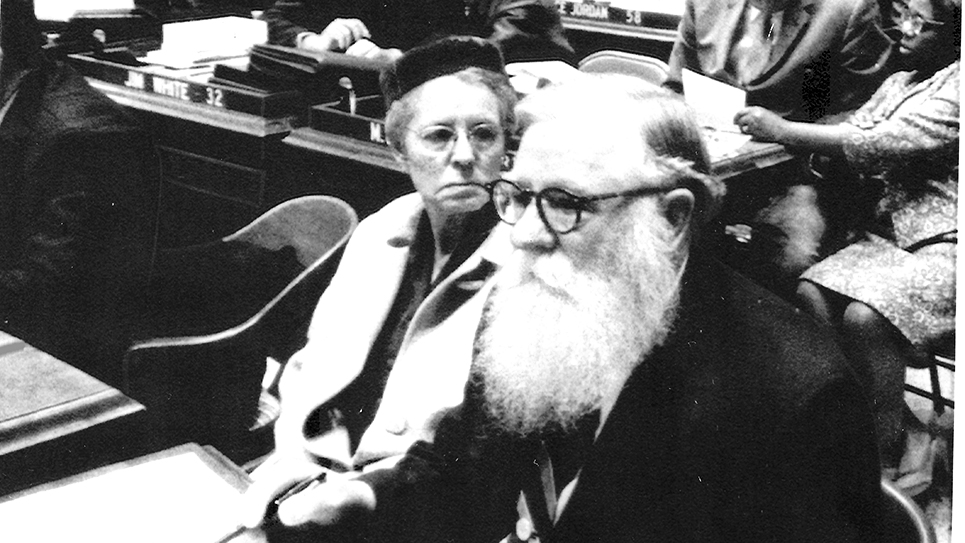

J.P. Kimbrell was a farmer by vocation, 5’8 and carried 225 pounds on his small frame. Bespectacled, Kimbrell wore a beard that vaguely gave him the appearance of an Appalachian Santa Claus. Kimbrell was no stranger to politics, having been elected twice to serve as judge of the General Sessions Court and twice barred from assuming the office because he was not an attorney. That was a serious point of contention for Kimbrell who had run for the legislature on a platform of allowing non-attorneys to serve as judges of the General Sessions Court, which was the case in most of Tennessee.

John Haile, a reporter for the Tennessean, hurried to Lawrence County to meet the newly elected legislator. Kimbrell, according to Haile, wiped away a coffee stain from his beard with the back of his hand and poked the surface of the table “with a stubby finger.” “Put your pen down,” Kimbrell commanded, “this is off the record.”

Haile quickly concluded J. P. Kimbrell was no crank or kook. While the farmer sported a “shaggy beard” the newspaper reporter discovered the man who quite possibly held the fate of who organized the coming legislature in his pudgy hands was sharp of mind and possessed “the desire of a young man to change the world around him.” J. P. Kimbrell was the solitary Independent in a House of Representatives divided between the Republicans and the Democrats. John Haile found Kimbrell’s “independence is not limited to a party label.” “He is a man independent in thought, action and outlook,” Haile wrote. The question in the mind of everyone who followed the doings of the Tennessee General Assembly wondered what the “philosopher-farmer” would do come January 1969.

J.P. Kimbrell cheerfully admitted he had been raised as a Republican and had voted accordingly, supporting every GOP nominee for president since the 1920 election. Yet Republicans could not be heartened by Kimbrell’s conversation with John Haile. “I owe the Republican party nothing,” Kimbrell snapped. “The Republican party has deserted its own principles.” Elected from a district comprised of Lawrence, Giles and Wayne counties, Kimbrell had deliberately set out to run as an Independent rather than as a Republican. Acknowledging he had been contacted by “a couple” of prospective GOP candidates for speaker, Kimbrell was quick to say he had made “no commitments to anyone.”

“I’m just letting every day take care of itself,” Kimbrell explained. “I’m just keeping my mouth shut. I’ll make my decisions at the last moment.”

Kimbrell did say he certainly intended to introduce a bill to repeal the requirement a person must be a lawyer to serve as the judge of the General Sessions Court in Lawrence County. Kimbrell had sued in the courts and had failed. Otherwise, J. P. Kimbrell really said very little about himself and his background. John Haile wrote little was known of Kimbrell’s personal life other than he had apparently been a teacher prior to 1931 when he worked his farm full-time. Yet the farmer had a stubborn streak that was well known. Kimbrell challenged his having been fined $25 for assault and battery all the way to the Tennessee State Supreme Court, where he was his own lawyer. To the surprise of virtually everyone, Kimbrell won his case. Kimbrell had shot and wounded a stranger who had trespassed on his farm eighteen years earlier.

Yet Kimbrell was a farmer who didn’t farm. There were no chickens, cattle or pigs on his farm. J. P. Kimbrell’s grandfather had lived to be 107 years old and his father 93. As to his beard, Kimbrell told a reporter from the Memphis Press-Scimitar, “My grandfather had a beard. My father had a beard. It’s the dignity of my family tradition.”

Kimbrell said there was not much of interest about his personal life. “Let me give you some philosophy,” Kimbrell told reporter Null Adams. “All the power a man has is his personal life. If he starts telling about it, it’s like a leaking tire on your car. Soon it’s all gone and you are flat just like a flat tire.”

Evidently, Kimbrell had inherited enough property and money to get by. He still lived on the same farm where he was born. Kimbrell cheerfully described himself as a “drop out” from most everything, including farming and teaching. Kimbrell had no hobbies except for reading and shunned “hog meat,” which he proclaimed “unhealthy.”

At the root of Kimbrell’s quarrel with the legal system was a fundamental distrust of lawyers and judges. Kimbrell’s campaigns for judge of the small claims court was precisely because he felt the voice of the people was being ignored. The fact he won twice and was denied the office to which he had been elected by the people only reinforced his belief. “Justice is now just a word you find in the dictionary,” Kimbrell said bitterly.

- P. Kimbrell pointed to the “Warren Court.” “The decisions of the Supreme Court have ruined this country. The Earl Warren Court has no respect for the people.”

John Haile noted, likely with some surprise, J. P. Kimbrell had a nimble mind, and the reporter wrote the farmer could quickly recall “points of law, statements by Thomas Jefferson, Neville Chamberlain and Will Rogers, events of the Constitutional Convention and, more recently, returns from boxes in his legislative district.”

Haile wrote J. P. Kimbrell was outwardly calm of demeanor and his eyes “keen” and while he talked to the reported, the farmer had a napkin in his hands, which soon “became only shreds of paper.”

“There’s no such thing as quitting as long as there’s anything to stand on at all,” Kimbrell told John Haile.

Unlike every other freshman legislator, J. P. Kimbrell received enormous attention from the news media of the day. Kimbrell even turned down an interview with CBS, but his likeness appeared in most Tennessee newspapers. The speculation of the Republicans and Democrats having exactly the same number of legislators kept Kimbrell and his whims in the headlines. In late December, Kimbrell made additional headlines when he raised the possibility he might not vote at all in choosing a speaker for the House. “I’m not saying I will not vote when the matter comes before the House,” Kimbrell said. “But I am saying there are pitfalls either way I vote and I’m turning over the idea of not balloting on the issue.” Both parties had chosen their nominees for Speaker; the Republicans had chosen William L. “Bill” Jenkins while Democrats settled on Pat Lynch.

As Republicans assembled in caucus immediately prior to the legislative session, Kimbrell braved icy roads to attend, where he was the center of attention. Kimbrell was asked to speak and he was rewarded with laughter when he quoted William Jennings Bryan, saying, “I ain’t got nothing agin nobody.” The GOP legislators gave him a round of applause as J. P. Kimbrell took his seat.

The drama ended with the election of Bill Jenkins as the first Republican to occupy the Speaker’s chair since 1865. Yet J. P. Kimbrell proved not to be the deciding vote in the choosing of a GOP Speaker. That honor (or infamy depending upon the observer) fell to Knoxville state Representative Robert “Bob” Booker of Knoxville. Booker was the only Democrat in the Knox County Legislative delegation, and he was the only member to switch and vote for the other party’s nominee for Speaker of the House. As expected, J. P. Kimbrell voted for Jenkins as well, but the East Tennessean was already elected due to the vote of Bob Booker. The final vote was 51 for Bill Jenkins and 48 for Pat Lynch.

Oddly, the peak of J. P. Kimbrell’s notoriety occurred prior to his taking the oath of office. Kimbrell served his term in the House of Representatives and ran for reelection as an Independent in 1970 against both a Democrat and Republican. Once again, the law conspired against J. P. Kimbrell. As required by the law, Kimbrell filed his original petition in his own Lawrence County, but he had filed copies in Wayne and Giles Counties when the law required original petitions to be filed there as well. As a result, Kimbrell’s name was not on the ballot in two of the three counties he represented. J. P. Kimbrell lost the 1970 election.

Undaunted, J. P. Kimbrell ran again in 1972 to reclaim his seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives. Yet again, Kimbrell ran as an Independent. This time the election was won by the Republican candidate.

Kimbrell’s political activity was diminished by old age and infirmity. The former legislator suffered a stroke and spent time in and out of the hospital. The eighty-one-year-old J. P. Kimbrell died in Crockett General Hospital in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.

Suffice it to say, few freshman legislators have ever enjoyed basking in the limelight as did J. P. Kimbrell.