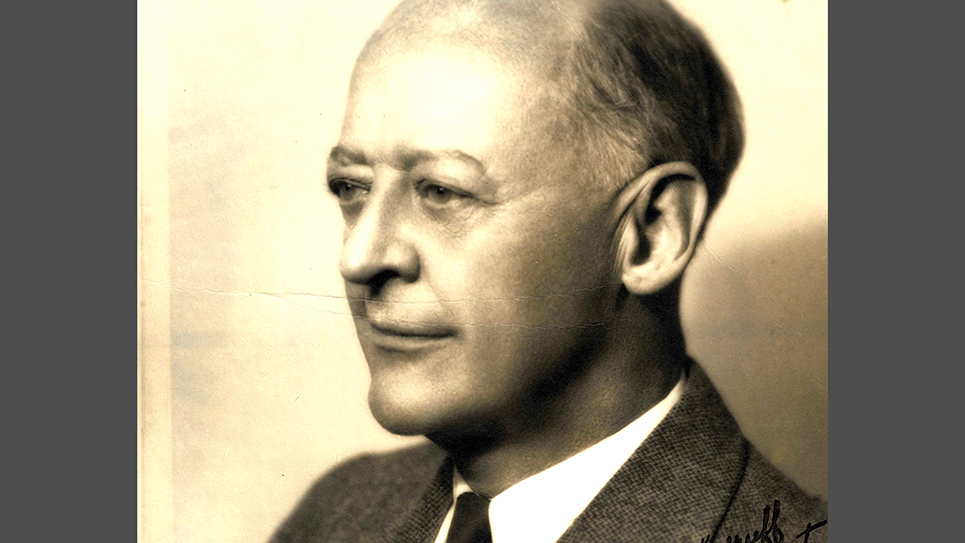

James W. Wadsworth of New York

By Ray Hill

The name James Wolcott Wadsworth Jr. is rather reminiscent of “Gilligan’s Island” and Thurston Howell III. To say that James Wadsworth was well-connected is likely a gross understatement. His grandfather, James S. Wadsworth, was a general during the Civil War; his father, the elder James Wolcott Wadsworth, served as a congressman for twenty years, as well as the comptroller of the State of New York. His wife, Alice, was the daughter of John Hay, Secretary of State to Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt and one of President Abraham Lincoln’s two personal secretaries. John Hay was also Lincoln’s biographer. Wadsworth was the father of James Jeremiah Wadsworth, who became the United States Ambassador to the United Nations; he was also the father-in-law of United States Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri, who was married to Wadsworth’s daughter, Evelyn. Through his daughter Evelyn, James Wadsworth was the grandfather of Missouri Congressman James Symington. The Symingtons were Democrats while Wadsworth was a Republican.

James Wadsworth lived in the family home in Geneseo, New York, where he had been born. A year after graduating from Yale University, Jim Wadsworth volunteered as a private in the Volunteer Army during the Spanish-American War. Elected to the New York House of Representatives, Wadsworth was elected speaker with the support of President Theodore Roosevelt at age twenty-eight. Yet Wadsworth fought with Roosevelt and New York Governor Charles Evan Hughes as the speaker was adamantly opposed to the idea of instituting primary elections to select nominees for offices. At the time, Jim Wadsworth was the youngest person to be elected Speaker of the House in New York.

Wadsworth spent several years in Texas after his service in the New York General Assembly. Wadsworth’s aunt, Cordelia, was the widow of Irish magnate John “Black Jack” Adair. Mrs. Adair asked her nephew to come to the JA Ranch, located near Amarillo, and become the general manager. Years later, Wadsworth recalled his time on the ranch and joked that he had not been able to change clothes for twelve days “and fully expected the Board of Health to be after me.”

By 1912, Jim Wadsworth had returned to politics, running for lieutenant governor, but lost. In 1914, New Yorkers cast their votes for the first time to popularly elect their own United States senator. James W. Wadsworth Jr. was the Republican nominee for the United States Senate in a three-way and beat Democrat James W. Gerard and Bainbridge Colby, who was the Progressive nominee and would later serve as Woodrow Wilson’s last Secretary of State. Wadsworth was reelected to the Senate in 1920.

Wadsworth sought a third six-year term in the Senate in 1926, facing Democrat Robert F. Wagner. Wagner was a stalwart member of the Democratic Tammany Hall political organization and was elected. Bob Wagner became one of New York’s most popular elected officials and passed some of the most significant legislation during the New Deal years under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Wadsworth’s defeat was due to a spilt inside the Republican Party over prohibition. An ordinarily Republican state senator ran as an “Independent Republican” in the general election, siphoning off 231,000 votes while Wadsworth lost to Wagner by 116,000 votes.

Wadsworth did not pine away from being out of office, rather he farmed 7,000 acres of his estate himself. He rented out an additional 5,000 acres and directed the work of thirty-five men. The farm had been in the Wadsworth family since 1797.

James W. Wadsworth was out of public office for the next six years, but when the incumbent congressman from the upstate Rochester district retired in 1932, Jim Wadsworth ran and was elected. Wadsworth is one of a handful of men who have been elected to the United States Senate and left that body to return to Congress as a member of the House of Representatives.

Isaiah Berlin, who was reporting back to the British Foreign Office, wrote a number of brief word portraits of senators and congressmen, especially those on the committee on foreign relations and foreign affairs. Berlin wrote Wadsworth was “one of the most forceful and independent-minded men in Congress and a highly skilled parliamentarian.” Berlin noted Jim Wadsworth was “highly respected and well-liked.” Unlike many of his Republican colleagues, Wadsworth was quite supportive of much of President Roosevelt’s foreign policy initiatives. FDR’s domestic program was entirely another matter and Congressman Wadsworth fought the most of the New Deal ardently.

Wadsworth most certainly did not approve of the tax and spend program of Roosevelt’s New Deal. The congressman wondered, “What of the men and women of tomorrow? Is it not inevitable that taxes will absorb all their savings?”

Standing on the floor of the House, Congressman Wadsworth had received a telegram from the manager of his farm. Wadsworth grinned and told his colleagues, “This great bureaucracy of ours has given me permission to sell my own wheat. Eventually maybe we will learn that we never get anything for nothing. For every handout, we yield up a right, a freedom.”

Much of the success of the passage of the Lend-Lease program owed its success in the House to Jim Wadsworth. Congressman Wadsworth had supported Lend-Lease

Wadsworth was routinely reelected until his retirement from the House in 1951. The Troy Times Record noted Wadsworth had a contrary streak in his political makeup, not fearing the public’s wrath. It seemed beneath the notice of Jim Wadsworth to deign to acknowledge a particular position was contrary to the popular thinking of the moment. One such case was prohibition, the issue that had most likely cost Wadsworth his seat in the United States Senate. When the former senator and congressman died, the Troy Times Record published an editorial stating Wadsworth “was close to the top echelons in statesmanship.” “Had it not been for a disposition to oppose strenuously men and measures which threatened to overturn traditional mores he would have come even nearer the apex.” The Times Record marveled at Wadsworth’s opposition to giving women the right to vote when women’s suffrage was “on the very eve of its success.” Yet the editorial readily acknowledged Jim Wadsworth believed in what he stood for. Senator Wadsworth was no hypocrite; he did not drink “wet” and vote “dry.”

It had to be a source of satisfaction one of his first actions as a newly elected member of the House of Representatives was to vote to repeal prohibition.

As a member of Congress, Jim Wadsworth was frequently concerned about the spending of taxpayer dollars. Wadsworth liked to recall the story of when he had visited Washington in 1905 to see his father, who was then a congressman and chairman of the House Agriculture Committee. Upon arriving at his father’s office, “Young Jim” found his worried father pacing. “When I asked him what was the matter, my father replied:

“Boy, do you realize no matter how hard I work, I can’t get the Agriculture Department appropriation below $15,000,000?”

At the time, the Agriculture appropriation before then-Congressman Wadsworth was $764 million. Slowly, Wadsworth told his colleagues at the conclusion of his story, “If there is any such thing as turning over in graves, my revered father is doing so now.”

Wadsworth retired from Congress due to failing health, but the former congressman was recalled to duty by President Harry Truman, who asked Wadsworth to serve as the Chairman of the Nation Security Training Commission, a new entity created by Congress to draft America’s first universal military Training program. Wadsworth worked hard to come up with a workable proposal, which was sent to Congress. The former congressman watched helplessly as his one-time colleagues smothered the proposal to death in committee and buried the body in a bottomless hole. That occurred the day after Wadsworth had entered the hospital. Wadsworth readily admitted his greatest disappointment as a congressman had been his failure to pass universal military training. Wadsworth thought politicians burying such legislation was an insult to the intelligence of the American people.

Even during his service in the U.S. Senate, Wadsworth had been a strong advocate of military preparedness. It was Senator James W. Wadsworth Jr. who had exposed a serious defect in the mobilization of the National Guard in 1916, just prior to America’s entry into the First World War. Wadsworth remembered his own service during the Spanish-American War, stating, “How wretchedly trained we were!” Wadsworth liked to say he was the only person in Congress who entered the Army as a private and came out with the same rank.

It was during his tenure as a member of the United States when Senate Wadsworth first introduced a national defense bill proposing universal military training while chairman of the Military Affairs Committee. While a majority of the committee favored Wadsworth’s proposal, it was pared from the bill before it reached the floor of the Senate. Apparently, the leaders of the Senate had told committee members universal military training had no chance of passing the full Senate.

Congressman James W. Wadsworth Jr. was the House sponsor of the legislation that allowed the first peacetime draft in American history. Wadsworth had been a proponent of Selective Service even before President Franklin Roosevelt. Wadsworth had consistently voted against the neutrality bills pushed by the large bloc of isolationists in Congress. Along with Senator Edward Burke, a Nebraska Democrat, Wadsworth was responsible for passing the draft bill, which had expanded America’s training program before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. It was as timely as it was wise.

Originally, the Roosevelt Administration was quite cool toward the Wadsworth-Burke Bill, giving little notice to the legislation and showing even less interest. Developments across the globe quickly changed the administration’s thinking. The Roosevelt Administration even tried to horn in on the credit for having had the foresight to pass the Wadsworth-Burke Bill. On the day of the first Selective Service drawing, it was President Franklin Roosevelt himself who drew out the pellet with the fateful number. While a goodly number of Washington elites had been invited to attend the ceremony and the drawing, Congressman Jim Wadsworth and Senator Edward Burke had pointedly not been asked to attend. As that began to become commonly known amongst reporters, the White House hurried acted to cover up its mistake by pleading with Wadsworth and Burke to come to the ceremony.

Jim Wadsworth had hoped to return to his farm, where he raised vegetables, beef and dairy cattle, sheep, as well as producing milk and wool. Yet for all his love of farming, Wadsworth would not permit photographers to take a picture of him in his overalls, not even in election years.

The congressman was suffering from cancer and underwent abdominal surgery in 1951. The operation did not stop the relentless advance of the cancer and James W. Wadsworth Jr. died June 22, 1952, at age seventy-four.

The Rochester Democrat & Chronicle remembered James W. Wadsworth Jr. as a man with an excellent sense of humor who had played first base on the Geneseo town team. The editorial concluded, “Above all, we shall remember James W. Wadsworth as a warmly human individual – – – of rare charm – – – a gentleman unafraid, who served his country well.”

President Harry Truman sent out a statement saying, “Mr. James Wadsworth, who died last night, was a man to whom the country is greatly obligated. He was a man of independent thought and action who believed strongly in military preparedness.” Truman readily acknowledged it had been Jim Wadsworth who had “promptly and effectively” moved “to alert his associates in the Congress to the importance of military training in the country’s defenses.” Truman praised James W. Wadsworth Jr. as “a patriot and an outstanding public servant, not only of his state but of the whole country.”

That is a mighty fine epitaph for any American.