The best-selling author Pearl Buck once wrote, “If you want to understand today you have to search yesterday.” History is comprised of the high and the low and everything in between. The “great” historical figures every child (at least in my day) grew up learning about – – – George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Booker T. Washington – – – are merely one part of history. No less interesting are the folks who aren’t familiar to the average person.

One thing that is notable about the U.S. House of Representatives is the fact is it precisely what the founders of the Republic intended: the People’s House. While it may make some blush, all too often congressmen and congresswomen are the reflection of the communities from which they come. One constituency in Massachusetts convinced a former president of the United States to stand for election to Congress. John Quincey Adams remains the only former president to be elected to the House (Tennessee’s Andrew Johnson tried and failed, although he was elected to the U. S. Senate following his time in the White House) after having served as our country’s chief executive. Yet Adams consented to serve in the House of Representatives with the understanding he would never deign to actually campaign for office. That district kept Adams in office, although he had opponents run against him, until he died. Some congressmen rise to become enormously powerful and productive; others either become or always were scalawags and rogues, while others still are thieves and blackguards. Whatever a congressman or congresswoman is, he or she is truly one of the people.

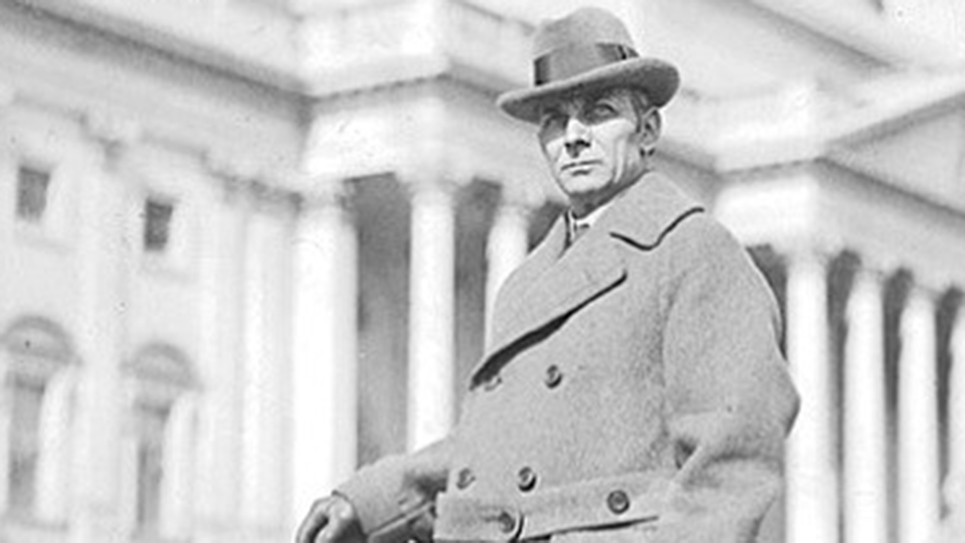

There are always stories to be told, whether we have heard of the person or people involved or not. The name of Milton Andrew Romjue is almost surely unheard of by most readers, yet for twenty-four years he represented a district in Missouri in the House of Representatives. The descendant of a Frenchman who was a friend of the celebrated General Lafayette, who was a friend to the American people and a hero of the American Revolution, John Henry Romjue was an early Missouri pioneer. The future congressman was known as “Andy” to friends and family and demonstrated a determination to better himself early on, putting himself through the University of Missouri’s law school. As one of nine children, quite likely Romjue learned how to do for himself early on. Throughout his long political career, Andy Romjue was well served by possessing a good sense of humor and was known as an excellent storyteller. Associates of Andy Romjue thought the future congressman had a remarkable gift of reading people. Like any really good politician, Romjue liked people. Of course, not every prospective officeholder does and usually voters can readily discern the difference.

Andy Romjue graduated first in his class in 1904; two years later the young attorney was the Probate Court Judge of Macon County, a post he held until 1914. In 1916, Congressman James Tilghman Lloyd decided to retire, and Andy Romjue ran to succeed him. Facing four opponents inside the Democratic primary, each of whom had a local base, Romjue eked out a win with only 28% of the votes cast. Missouri’s First Congressional District was ordinarily Democratic, and he won the general election with a solid majority.

Almost immediately Andy Romjue was faced as a freshman congressman with the prospect of voting to declare war and send American boys overseas to fight. Romjue’s time in Congress included both World Wars. Not everybody was happy with the freshman congressman’s service, and he faced Sidney Foy in the Democratic primary in his 1918 reelection campaign. Foy had run two years earlier and while he ran a respectable race, he lost decisively. Romjue faced a strong GOP candidate in Frank Millspaugh but managed to win reelection comfortably. Two years later, Millspaugh ran again and turned the tables on Congressman Romjue as 1920 was the year of a Republican tidal wave.

Romjue ran for his old seat once again in 1922 and proved his personal popularity by winning the Democratic primary against two opponents with more than a majority of the ballots cast. Romjue pounded Millspaugh and the Republican Congress and won the general election easily to return to the House of Representatives.

Romjue’s tenure in Congress was seriously threatened in the 1932 election due to the failure of the state legislature to redistrict. That failure necessitated every aspirant for Congress having to wage a statewide campaign to be elected. Missouri had two potent political machines in its two largest cities, St. Louis and Kansas City. The Kansas City machine backed Tom Pendergast, while another rival political boss, Joseph Shannon, had himself elected to Congress and was one of the candidates running for an at-large seat.

There were thirteen seats to be elected and Andy Romjue was opposed by both big city machines, especially by that of Tom Pendergast in Kansas City. Romjue narrowly made it through the Democratic primary, running eleventh out of the thirteen victors. Yet Congressman Romjue was no political reformer; Andy Romjue knew something about patronage and favors himself and gleefully rewarded his friends and supporters. Romjue also had a well-deserved reputation for not forgetting his political opponents and enemies. Once Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected in 1932 and Congress boasted big Democratic majorities, that became an important point, as Republicans were displaced from well-paying federal posts and replaced with deserving Democrats.

Like most politically successful congressmen, Andy Romjue depended upon a close network of friends and advisors in each of the counties he represented in Congress. Never too busy to keep an eye on developments back home, Congressman Romjue knew what was happening inside his own district. During the 1928 and 1932 elections, Romjue was the director of the State Democratic Headquarters for Missouri, which gave him some extra claim on jobs and positions with the Roosevelt Administration. Yet Andy Romjue did not get along with everyone. Clarence Cannon had first come to Congress from Missouri in the 1922 election. Only 5-foot-7, Cannon was a scrappy and somewhat cantankerous man who was an expert on parliamentary procedure and renowned for using his fists when affronted. In 1933, Andy Romjue and Clarence Cannon got into physical fights twice in two days.

Evidently, the second spat was the result of lingering hard feelings from the first altercation, which was still on the minds of at least one of the combatants. Reportedly, the fight occurred when Romjue and Cannon ran into one another on the first floor of the Old House Office Building.

The origin of the dispute between the two Missouri congressmen remains a bit hazy, but reputedly it was a disagreement over a campaign check. Cannon’s official office was on the fourth floor of the House Office Building, but he also had a small office on the first floor as the chairman of a subcommittee of the Appropriations Committee. As Clarence Cannon was leaving the rooms of the Appropriations Committee to go to his office on the fourth floor, Congressman and Mrs. Romjue emerged from the elevator. Cannon asked about a $45 check from Romjue for the Democratic campaign fund. Congressman Romjue said he would peruse his canceled checks and if he did not find he had paid his share of the fund, he would send along another check. According to a witness who remained anonymous, Cannon told his colleague, “You made an unprovoked assault on me yesterday” and punched Romjue in the face in front of the congressman’s wife.

The bad blood between Andy Romjue and Clarence Cannon had been simmering for some time. The very first altercation began in the rear of the House chamber behind the railing where the 6-foot Romjue was supposed to have told Cannon he was a “double-crosser,” a liar and then uttered something “for which no red blooded man will stand” and slapped the diminutive congressman across the face. While the accounts of the disagreement between the two Missouri lawmakers varied, sometimes significantly, the common thread in all of them was Romjue had been the aggressor. One thing that had seemingly rubbed Romjue wrong was Cannon’s support for their fellow Missouri congressman Clyde Williams to serve on the House Democratic Steering Committee, a spot Romjue likely coveted for himself.

Romjue had noted Cannon had received very good committee assignments from the House leadership and had promptly voted against President Roosevelt’s economy bill. Whatever the case, the Missouri Congressional delegation quickly circled the wagons and told inquiring reporters they had been collectively “sworn to secrecy.” Congressman John Cochran of St. Louis was approached by a reporter and before the journalist could say anything, snapped, “. . .if you are going to ask me about the fist fight between two Missouri members I don’t know anything about it.”

When newspaper reporters began sniffing around the purported pugilists, Congressman Romjue was supposedly confined at home due to “influenza.” There were those unkind enough to say the Missourian had been confined to home with a split lip and black eye. The fight had been broken up by Congressman Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota, who said he had shoved one of the riled congressmen into the elevator and sent it in an upward direction. All Lundeen would say as to the person’s identity is it was a “former House clerk.” Clarence Cannon had worked as a Clerk of the House under Speaker of the House Champ Clark, who was also from Missouri.

Discord between Andy Romjue and Clarence Cannon was nothing new. Although he had served two terms prior to his defeat in 1920, Romjue had come back to the House in the 1922 election when Clarence Cannon had won his first term. Clearly, there were hard feelings between the two men, and they certainly didn’t much like one another. Romjue may have felt some jealousy toward the hardworking Cannon, who was well-positioned in the House.

In 1939, Andy Romjue became the chairman of the House Post Office Committee. While hardly a glamorous assignment, nor was it a much sought-after committee like that of Foreign Affairs whose membership were wined and dined throughout Embassy Row, it was a mighty practical assignment. Considering the rural nature of Romjue’s congressional district, it brought the congressman considerable patronage. Considering the country had entered into a serious recession in 1937, good-paying jobs were still scarce as hen’s teeth. Congressman Romjue was especially active in the appointment of postmasters and postal workers throughout his district. Those appointees largely remained loyal to Romjue and several of them would let the congressman know what kind of campaign materials were being sent out by his political opponents. Others provided Romjue with the names and addresses of voters who were undecided so that the congressman could get in touch with them.

Well before there were pensions for ex-servicemen, Congressman Romjue was very active in sponsoring the special bills required to provide for the widows and orphans of those who had been killed, as well as providing for those who were disabled. Romjue always paid close attention to correspondence from those needing his help, like veterans. Likewise, Romjue heartily supported pensions for the aged and relief for farmers, many of whom were destitute or barely scraping by.

Following redistricting in 1940, M. A. Romjue faced a closer-than-ordinary contest in the general election. 1942 brought a strong Republican challenger from businessman Samuel W. “Wat” Arnold, an old schoolmate of Romjue’s. The Second World War was going badly all over the globe for the Allies in 1942 and the people were restless. Republicans made significant gains in both houses of Congress. The Show Me State was no exception, and several longtime Democratic incumbents lost their seats in Congress. One of those was Andy Romjue, who had not waged as active a campaign as he might have otherwise, as he was worried about his wife who had been injured in an automobile accident earlier.

Andy Romjue retired to his farm where he lived for another twenty-six years, dying at the ripe old age of ninety-three. © Ray Hill 2023