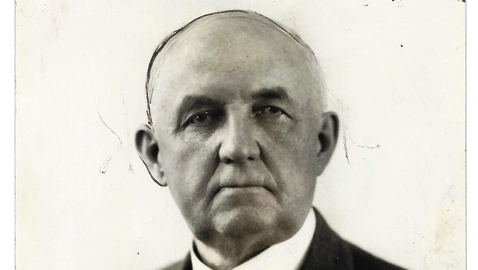

For a time, there was no more influential Republican in the State of Tennessee than Newell Sanders. Sanders was a Republican at a time when the GOP was at a distinct disadvantage in the Volunteer State, yet he helped to build his party and became a power in the national councils of the GOP. Extraordinarily successful in business, Newell Sanders was a devoted family man. Once when being interviewed by a reporter, Sanders said, “I don’t want a word to go out about myself.” Newell Sanders explained he preferred not to have anything at all written about him unless his wife was mentioned as well.

“While I worked, she saved,” Sanders told the reporter. “She is entitled to as much credit for whatever I may have done in every relation of life as I am.”

Kenneth D. McKellar, who was a congressman from Memphis when Newell Sanders briefly served in the United States Senate, later recalled that Sanders was “devoted” to his wife and their married life was “very beautiful.” The two were also diametrically opposed politically and would contest one another in 1922 for the U. S. Senate.

Newell Sanders was as bitterly a partisan Republican as McKellar was a Democrat. When appointed to serve in the United States Senate in 1912, Sanders served alongside Luke Lea, one of the most controversial political figures of his time. Yet the two men were personal friends while fighting one another vigorously politically. Both men were strong advocates of “temperance,” meaning they favored prohibition of alcoholic beverages.

Newell Sanders was not a native Tennessean; in fact, he was a Hoosier, having been born in Owen County, Indiana on July 12, 1850. After attending college, Sanders operated a small bookstore, which he closed in 1877 when he moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Sanders later laughingly recalled the bookstore had been the very definition of a failed business.

It was in Chattanooga that Newell Sanders first experienced real success in business and eventually owned several factories that manufactured farm equipment. Sanders rose in the business world and participated in the community and political life of his adopted city. Sanders served on the local Board of Education and as a city alderman. With business success, he was invited to join the board of directors of several enterprises, not the least of which was the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railroad. Sanders was also president of the Chattanooga Steamboat Company.

Eventually Sanders would come to wield so much influence inside Tennessee’s Republican Party that he was denounced as a “boss”.

Sanders was not afraid to fight for his convictions and some of the Republican state conventions became rather violent affairs between rival factions. Newell Sanders was a strong proponent of H. Clay Evans from Chattanooga and was attacked by a fellow delegate who was committed to the rival faction of the Tennessee Republican Party, headed by Walter P. Brownlow. The two exchanged heated words until, according to the New York Times, Sanders was “almost choked into insensibility.”

The two factions were feuding when the national Republican Party split between President William Howard Taft and former president Theodore Roosevelt. Sanders, as Chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party, had been warned the faction led by Congressman Walter P. Brownlow was “inflamed” by whiskey, rowdy and just down right dangerous. Friends told Sanders his personal safety was at risk but the chairman ignored the warnings and tried to open the convention. Sanders was assaulted with one eyewitness recalling the senator’s suit coat being torn off his body and shredded. His pocket watch and wallet were later found lying on the floor where he had been accosted. It took Sanders an hour to reach the podium, but reach it he did, albeit bloody and battered.

Once at the podium, Sanders was attacked again and a group of Brownlow supporters literally tried to throw the Chattanoogan off the dais. The situation became even more dire when one fellow produced a hatchet and raised it above his head, intent upon doing even greater harm to the bleeding Sanders.

Bob Sloan, a local sheriff, intervened, whipping out his pistol and barking, “If anyone dares touch Newell Sanders, I’ll kill him, so help me God.”

It was not an idle threat and perhaps saved the life of Newell Sanders.

The Brownlow adherents sobered up and melted away that same night. The next day, Sanders presided as a delegation committed to the renomination of President Taft was elected.

Despite having been literally kicked, beaten and mauled, Newell Sanders, who knew the men who had attacked him, never uttered a single word of condemnation against any of them.

It was Newell Sanders who managed H. Clay Evans’ gubernatorial campaign in 1894, a campaign the Chattanoogan almost surely won, but the election was brazenly stolen by Governor Peter Turney’s supporters.

Even his opponents recognized Newell Sanders’ determination. One friend said of Sanders, “When Newell Sanders starts he knows whither he is bound and he keeps going. It may take him two years or five years to get there, but he invariably arrives at his destination. If he were not a good Baptist I would say that all hell couldn’t stop him.”

Newell Sanders promoted the candidacy of Ben W. Hooper for the GOP nomination for governor in 1910. The normally dominant Democratic Party was torn asunder by infighting, which was largely over the highly divisive issue of prohibition. The 1908 gubernatorial primary had been a brutal affair with Governor Malcolm R. Patterson challenged by former U. S. Senator Edward Ward Carmack. Senator Carmack was the champion of the more rural areas and was adamantly against liquor and spirits. Governor Patterson who freely admitted he enjoyed a drink now and then, was personally and politically “wet”. Patterson won and Carmack, a newspaper editor by trade, began writing vitriolic editorials verbally assaulting the governor and many of his friends. One such friend was Colonel Duncan B. Cooper, who profoundly resented being skewered in print regularly. Colonel Cooper demanded Carmack cease his attacks, but the stubborn redheaded editor refused. Carmack met Colonel Cooper and Cooper’s son Robin on a Nashville street corner. Shots were fired and Edward W. Carmack lay dead in the gutter.

Carmack’s assassination completely blew apart Tennessee’s Democratic Party. Governor Patterson’s pardoning Colonel Cooper caused an even deeper rift. Sanders helped to engineer the nomination of Ben W. Hooper over veteran Republican warhorse Alf A. Taylor. As Sanders had guessed, the intraparty warfare between Democrats gave the Republicans the opening they needed to win. Ben Hooper defeated Senator Robert Love Taylor in the general election.

Hooper had been an orphan, the result of an affair and was selling newspapers as a boy before being put into an orphanage. Hooper was later adopted by a physician who was in reality his biological father. Hooper had gone to Oklahoma for a time and reputedly made $150,000 by trading in real estate in the Sooner State. It was an enormous sum for the time, more than $3,500,000 in today’s currency. The former waif had been elected governor of Tennessee, which had been managed by Newell Sanders.

When Senator Robert L. Taylor died on March 31, 1912 following surgery for gallstones, Governor Hooper appointed Newell Sanders to fill the vacancy. Sanders was the first Republican to serve Tennessee in the United States Senate since William G. Brownlow in 1875; Sanders was the last Republican to serve in the U. S. Senate from Tennessee until Howard Baker’s election in 1966.

As an ardent prohibitionist, Senator Sanders sponsored a bill which prohibited interstate shipment of alcohol into dry states. The bill passed Congress and Sanders was aghast when his bill was vetoed by President Taft. Undaunted, Sanders helped to override the president’s veto and the bill became law.

Sanders served in the Senate until the legislature elected W. R. Webb, who only served from January 24, 1913 until March 4, 1913. Newell Sanders returned to his business interests and Republican politics. The GOP swept Tennessee in 1920 with seventy-two year old Alf Taylor finally winning the governorship. Republicans won congressional seats in the First, Second, Third, Fourth, and Seventh districts. Warren Harding carried Tennessee as well.

Perhaps thinking 1922 might be an equally good year for Republicans, Newell Sanders announced he would be a candidate for the United States Senate. Sanders challenged incumbent Kenneth D. McKellar, who had been the first U. S. senator elected by popular vote in Tennessee.

Sanders ran as a conservative, accusing McKellar of dangerously liberal sentiments. McKellar had perfected the art of constituent service and easily dispatched a robust challenge inside the Democratic primary, winning by a far greater margin than many supposed possible. During the course of the fall campaign rumors were rampant that Tennessee’s senior U.S. senator, John Knight Shields, would be appointed to the United States Supreme Court by President Harding. Senator Shields, a former justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court, very much desired to serve on the high court. Newell Sanders was rumored to be Governor Taylor’s choice to serve in the Senate should John Knight Shields receive the appointment to the Supreme Court. The rumors did little to aid Sanders’s actual Senate campaign. Already past seventy, Sanders was not able to wage an especially energetic campaign. He did have a core of support in the state as he controlled most of the federal patronage.

McKellar almost leisurely defended his record in the Senate and even those who did not admire the senator felt sure he would be reelected. Governor Taylor was defeated by Clarksville attorney Austin Peay and Senator McKellar beat Newell Sanders overwhelmingly. Sanders won 32% of the vote.

Newell Sanders remained active in business and political affairs, but his health became increasingly frail as he aged. He self-published a book of memoirs, mostly for his grandchildren. For the last several years of his life, the former senator suffered a variety of ailments. Sanders died peacefully at his home on Lookout Mountain on January 26, 1939 at age eighty-eight.

Newell Sanders held just about every office available to a party leader in his adopted state. Sanders was a man of strong opinions and convictions and he remained true to his beliefs. Newell Sanders held the respect and affection of his friends and the love of his family. Few could ask for more.