Re-electing the Senator: The Final Campaign of William B. Bate

By Ray Hill

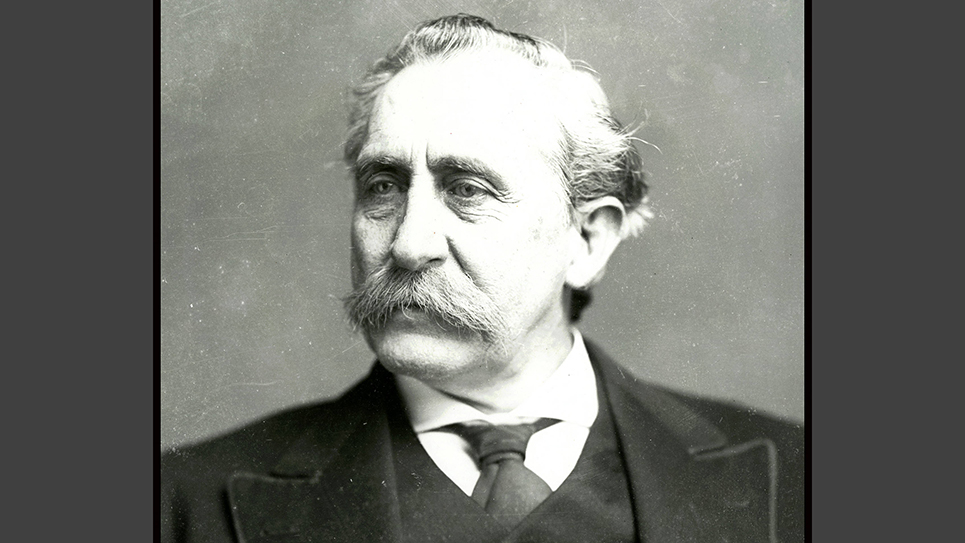

By 1903, only two men had ever been elected to a fourth term in the United States Senate from the State of Tennessee: Isham G. Harris and William B. Bate. The two men had several things in common: both were Democrats, both had mustaches, both had been Confederate generals during the American Civil War, and both had served as governors of the Volunteer State before being elected to the U.S. Senate. Another thing Harris and Bate had in common was that they both grew old in the service of Tennessee and Tennesseans. Senator Harris had died in 1897 at age seventy-nine. Senator Bate sought reelection when he was seventy-eight in 1904.

Somewhat bent with age, the white-headed Bate used a cane to get around and numerous prominent Tennesseans had waited hopefully for a senatorial vacancy during the years Bate and Harris served together in the U. S. Senate. Bate had a public image of being a man of great integrity at a time when many congressmen and senators were hardly idols of rectitude. Bate refused to accept free passage on trains, a common thing of the time offered by railroads and their lobbyists. Nor would General Bate even accept the pension due him as a veteran of the Mexican War while he collected his salary as a senator. Bate also had a reputation for paying close attention to his duties as a member of the United States Senate and took pride in his attendance record.

As always, ambitious men hankered for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Two former governors from Tennessee were widely known to ache to serve in the Senate and William Bate kept a careful eye on the both of them. In 1903, in anticipation of his campaign for a fourth term in the Senate, Bate told friends in Tennessee he believed former Governor McMillin would challenge him. McMillin had served twenty years in the U.S. House of Representatives before being elected governor in 1898. Reelected in 1900, McMillin retired in 1902 and cast his eye toward Washington, D.C. The former governor made no secret of his ambitions and by November of 1903 was traveling across Tennessee in the interest of his senatorial campaign. That same month the two aspirants traded barbs in local newspapers. Benton McMillin gave an interview to a reporter from the Nashville News. McMillin acknowledged a statement given out by Senator Bate to a competing daily in Nashville, the American.

“Yes, I noticed the interview Senator Bate gave to the American published in last Saturday’s paper. He states that ‘my competitor’ – – – referring of course to me – – – ‘has opened headquarters in Nashville.’ This is a mistake, as I have not opened headquarters here or anywhere else,” McMillin said. “I notice also that Senator Bate claims in an interview published in the Memphis Commercial Appeal that he will carry every county in the state except Benton, Henry and Shelby counties. I think a sufficient answer to this statement is contained in the fact that Senator Bate has seen fit to open headquarters in Nashville just twelve months earlier than he ever did before.”

Benton McMillin added he had just returned from Jackson, Tennessee, where he had been “on political business” before returning to Nashville. The former governor stated he was “thoroughly satisfied with the situation” before adding, “I think this is as much as I can say just now.”

Former Governor Robert Love Taylor, popularly known as “Our Bob” made a handsome living lecturing and during one of his speeches a fellow bawled out he should run for the United States Senate because “everybody’s fer yer.” “Our Bob” cast a sideways glance at his questioner and replied, “My dearly beloved fellow countryman, unfortunately I was not at Shiloh during the civil war nor was I at King’s Mountain or in the Praetorian guard, but when McMillin gets the British well whipped and Bate winds up the affairs of the southern confederacy, I expect to meet somebody at Phillipi.”

Senator Bate, accompanied by his wife, stopped in Chattanooga on the way by train to Nashville where the couple intended to remain until the next session of Congress. The general politely said he didn’t wish to give a formal statement to the reporter from the Chattanooga News, but he did agree to answer a few questions of interest to readers. “I look forward to the next session of the Senate” which Bate felt would be “a very stormy one.” Bate thought several pending questions before the Senate would cause “some severe fighting.”

“The principal question will be the amending of the rules of the Senate so that freedom of speech will be curtailed. This is a direct blow at the minority party, and will of course be fought by the Democrats in the Senate,” Bate said. The general said a member of the Senate could, under the present rules, talk for a month if he wished to do so and was “a protection to the minority party.” Bate thought the Democrats would unite behind a presidential candidate the following year in a bid to defeat President Theodore Roosevelt, who was expected to be a candidate for reelection.

According to the News, the aging senator was “looking well and enjoys excellent health.” While in Chattanooga, several friends called upon the Senator and Mrs. Bate in the lobby of the city’s Southern Hotel.

At the time, United States senators were elected by the Tennessee General Assembly. The route to the nomination was a mix of preferential primaries in some counties and conventions in others. Candidates campaigned, yet legislators were not legally obligated to follow the results. General Bate and former Governor McMillin were veteran campaigners, and both were intimately familiar with the towns and hamlets, as well as the cities that dotted Tennessee’s landscape. Bate had the advantage of being revered for his military service and gallantry and was popularly known as “Old Shiloh” in much of Tennessee. General Bate also had whatever power accrued through his eighteen years of service in the U. S. Senate.

Benton McMillin had been a popular congressman and equally popular governor. Indeed, McMillin was often referred to as either the best governor Tennessee had ever had or one of the best governors in the state’s history. Benton McMillin was a powerful orator and numbered his friends in the thousands. McMillin was a formidable challenger to the old warhorse. The two factions battled across the state, jostling for preference in the local conventions. The contest between the Bate and McMillin supporters in Savannah, Tennessee, was, according to the Columbia Herald and Mail, “very exciting” and it “closed very warm.” Senator Bate won the endorsement for the U.S. Senate over the former governor. That action was closely followed by Sumner County going for Senator Bate. Those supporters who favored Benton McMillin did not dispute the Sumner County convention results as it was also William Bate’s home county. The aged senator winning an endorsement from his home county was hardly a surprise, but the results of the convention in Overton County jolted the McMillin headquarters. Overton County had been thought to be a stronghold for the former governor and McMillin was highly surprised when the convention endorsed Senator Bate.

Trouble had been fermenting in Knox County where a local machine had been one of the outposts of opposition to the reelection of Senator William B. Bate. The Chattanooga News sniffed the Knox County machine “created the ugly party division existing there to no purpose.” The News opined, “Tennessee is going to stand by the old man until the last.”

A bitter fight between the Bate and McMillin factions was underway in Nashville as both sides perceived the importance, both political and psychological, of winning Davidson County. The Knoxville Sentinel reported neither camp was leaving anything “undone to gain advantage.” Many Democrats, at least according to the Sentinel, believed the winner of the Davidson County convention would win the Senate race altogether. That contest was won by McMillin.

McMillin had campaigned personally through the “byways and hedges” of Davidson County, pressing the flesh with “workmen at the bench” and visiting “shops and factory districts.” The former governor had won the contest for Davidson County, a result the Chattanooga Daily Times attributed to the “combination of the McMillin organization, Hearst money and the Louisville & Nashville railroad …” Senator Bate’s mistake, at least according to the Daily Times, was his apparently naïve belief in an incorruptible electorate.

As both candidates and their supporters worked fervently throughout the month of April before the primary election, more endorsements kept rolling in for Senator Bate. The old senator won a hearty endorsement from the Tenth Congressional District convention, which was comprised of Shelby, Tipton, Hardeman and Fayette counties.

State Senator John I. Cox, who would serve as acting governor for some time, was from Bristol, Tennessee. On his way from Chattanooga to his home, Cox issued a double endorsement of Judge Alton Parker for the Democratic nomination for president and General William B. Bate for the United States Senate. Cox said he supported both Bate and Parker and “don’t care who knows it.” While in Chattanooga, Cox stated his confidence Senator Bate would win the endorsement of Hamilton County. “Your county will certainly endorse him,” Cox said to a reporter, “for the Democrats of Hamilton County always do the right thing.”

Newspapers tried hard to keep up with the number of legislators committed to the two candidates. The tallies were calculated through shifting through the various conventions as well as candidates nominated for the legislature, many of whom declared themselves as favoring either Bate or McMillin. Some legislators ran and took neither side, saying they would abide by the wishes of their constituents.

Voters in Hamilton County went to the polls and Senator Bate, “the Hero of Shiloh,” swept both the city of Chattanooga and Hamilton County, carrying every ward and precinct. Bate’s tally in Hamilton County was an astonishing 83% of the votes cast.

Former Governor Benton McMillin’s defeat in Hamilton County was followed by more bad news: Senator Bate had received the endorsement of Sevier County. Newspapers reported both candidates intended to travel to Memphis for the primary election in Shelby County. Senator Bate was expected to campaign on behalf of a legislative ticket pledged to reelect him, while Benton McMillin was to campaign for a slate of candidates who promised to elect him to the U.S. Senate.

Benton McMillin seemed to have an advantage over Senator Bate in the contest for Shelby County’s delegates in the preferential primary. The former governor enjoyed the backing of Memphis Mayor Joseph John Williams and the local political organization. Yet Senator Bate’s popularity in Shelby County carried him to a sweeping victory over McMillin. It was a crushing blow to the challenger’s bid to unseat the old senator. The “Hero of Shiloh” had prevailed once again.

It was clear Senator Bate was increasing the number of legislators committed to his reelection, while former Governor Benton McMillin stubbornly clung to his hope he could be elected. By the end of May, that hope had apparently begun to diminish. Rumors were rife in Tennessee Benton McMillin would soon announce his withdrawal from the race for the Senate. It was clear to just about everyone Senator Bate had enough pledges to win the contest inside the state legislature. McMillin’s campaign manager hotly denied the rumors, insisted the campaign was going well, and complained the rumors were being circulated by a hostile press.

William B. Bate, “Old Shiloh,” was reelected to the United States Senate and hurried back to Washington, D.C. where he caught a cold at the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt. The cold rapidly turned into pneumonia and Senator Bate died on March 9, 1905, four days after beginning his fourth term in the United States Senate.

© 2023 Ray Hill