By Ray Hill

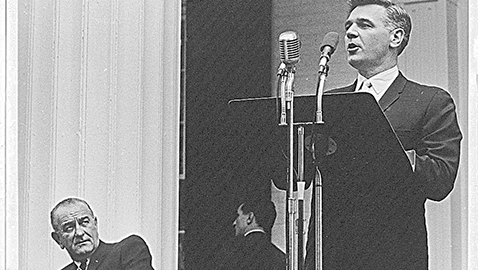

The passing of Richard “Dick” Fulton on November 28 at age 91 seemed to escape the notice of many Tennesseans, yet his life ought to be remembered by folks. The growth and success of Nashville is largely due to the vision and leadership of Dick Fulton. Twice a candidate for governor of Tennessee, Dick Fulton spent fourteen years in Congress and twelve as mayor of Nashville. With a profile that could have allowed him to play a President of the United States in the movies, Richard Fulton dominated the political landscape in Davidson County for decades.

Dick Fulton was born in Nashville in 1927 and attended the University of Tennessee. He returned to Nashville to help his brother run a local market. Dick Fulton’s emergence in politics was improbable. Fulton campaigned hard for his brother Lyle, who was running for the Tennessee State Senate. Lyle Fulton won a seat in the Tennessee State Senate, but died suddenly after being stricken with liver cancer. Dick Fulton became the candidate to replace his brother despite the fact he was only twenty-nine years old. Fulton was not old enough to serve in the State Senate and the Senate voted to deny him his seat. Fulton ran again in 1956 and was elected. Fulton also experienced his first political disappointment when he ran for Congress in that same year against incumbent Congressman Percy Priest. Priest, a former reporter for the Nashville Tennessean had originally been elected to Congress in 1940 as an Independent, quite a feat in a solidly Democratic city. Priest unseated one-term congressman Joseph Byrns, Jr., son of the late Speaker of the House. Percy Priest was wildly popular inside his Congressional district and Dick Fulton lost badly. Fulton was popular inside his own district and was reelected to the State Senate in 1958.

Dick Fulton ran for Congress again in 1962, facing incumbent J. Carleton Loser, who had won election to the U. S. House of Representatives following Percy Priest’s death in October of 1956. Loser had been the District Attorney for Davidson County and seemed to have a long career in Congress ahead of him. Evidently, Congressman Loser had not entrenched himself inside his district and Fulton’s challenge seemed to fall short of victory. Loser was declared the winner, but following an intense investigation by the Tennessean, it was readily apparent the Davidson County Election Commission was corrupt and the vote-count fraudulent. An attorney who was a childhood friend and supporter of Fulton’s, George Barrett, sued and had the election voided, causing a re-run of the congressional primary. Dick Fulton won the election handily and remained in Congress for the next fourteen years.

As a member of Congress, Dick Fulton was a progressive. Fulton was one of two Tennessee congressmen who voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1964; neither of Tennessee’s U. S. senators, Albert Gore and Herbert Walters, voted to support Lyndon Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964. Congressman Ross Bass of Pulaski was the only Congressional Democrat from a rural area to support the Civil Rights Act of 1964, while Fulton joined a handful of other Southern Democrats from big cities to support the bill; Charles Weltner of Atlanta, Claude Pepper of Miami, and four representatives from the president’s home state of Texas gave their votes in support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Bass won the late Senator Estes Kefauver’s seat later in 1964, barely edging past young Howard Baker.

Fulton’s vote for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was not only progressive in outlook, but evidently Dick Fulton’s own thinking had changed over the years. While running against Congressman Percy Priest, Fulton had criticized his opponent for not having signed the “Southern Manifesto”, which had been signed by 101 Southern senators and congressmen, outlining their opposition to integration, which included our schools. Neither Senators Kefauver or Gore signed the Southern Manifesto. While in Congress, Dick Fulton was easily the most liberal member of Tennessee’s Congressional delegation. Former governor Phil Bredesen, a former mayor of Nashville as well, recalled, “But it was his action as a Congressman – – – being one of the few from the South voting for the Civil Rights Act – – – that I admired most.” “The character and courage he showed was an inspiration to others for the rest of his life,” Bredesen said.

In 1975, the long-time mayor of Nashville, Beverly Briley retired and Congressman Richard Fulton was elected with more than 69% of the vote. Resigning his seat in Congress, Fulton served three terms as mayor of Nashville and while socially progressive, Dick Fulton was noted for being pro-business.

Dick Fulton sought the Democratic nomination for governor in 1978 facing two formidable challengers: Jake Butcher and Bob Clement, then a member of Tennessee’s Public Service Commission. Butcher won the primary with Fulton running a distant third, but the East Tennessee banker lost the general election to Lamar Alexander. Fulton tried again in 1986 and faced two other candidates in the Democratic primary: Ned McWherter and Jane Eskind. Fulton could not overcome McWherter’s popularity, especially in rural Tennessee, nor Eskind’s money. Yet again Fulton ran a distant third, never able to spread his appeal as a big-city Democrat inside his own party.

Richard Fulton retired from office in 1987 and returned to private life until 1999 when he surprised many by announcing he was running for mayor again. Fulton faced Bill Purcell, an able and shrewd young man who served as the state House Majority Leader. Purcell won the first primary easily, while Fulton won only 22% of the vote, barely winning more votes than City Councilman Jay West. Although he made it into the run –off, Fulton declared he would not campaign in the general election and threw his support to Purcell.

Former Mayor Purcell acknowledged Dick Fulton’s importance to Nashville, saying, “He was among the bravest and most beloved public servants in our history and he always be. He loved public service, but he loved Nashville most of all.”

Nobody who has ever served in public service could ask for a finer epitaph.