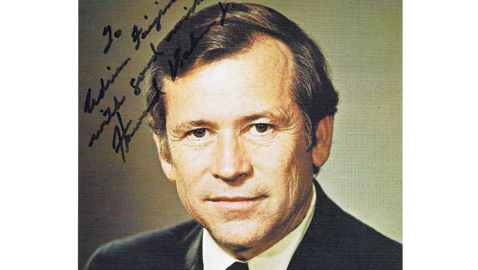

Although Howard Baker had not been selected as Richard Nixon’s running mate in 1968, his political star continued to rise. Even as Howard Baker’s political fortunes rose, 1969 was a difficult year for the Baker family.

Everett McKinley Dirksen was the last of his kind. A golden throated orator of a time gone by, the “Wizard of Ooze” to some, an artist and patriot to others. Dirksen’s only child, Joy, was Howard Baker’s wife. Everett Dirksen had been Minority Leader of the United States Senate for a decade when he died on September 9, 1969. Dirksen had first come to Congress in 1933 just as Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated as president. Voluntarily, Dirksen retired from Congress in 1948 due to failing eyesight. Two years later, his eyesight much improved, Everett Dirksen challenged Senator Scott Lucas, then the Majority Leader of the United States Senate. Dirksen won decisively and had remained in the Senate ever since. Senator Dirksen had been reelected to another six-year term in 1968 at age seventy-two, but the years had not been kind to the Illinois solon. Once somewhat stout and robust, Dirksen began to look thin and gaunt. The senator also looked older than his years. A very heavy smoker, the lines were deeply etched in his face beneath Dirksen’s carefully tousled gray curls. One reporter once commented, “His face looks like he slept in it.”

Dirksen’s magnificent voice helped him to become a recording artist and his Gallant Men album became a national best-seller.

When speaking at a fundraiser in Chicago in 1966, Dirksen had intoned, “No, you can’t eat freedom, or buy anything with it. You can’t hock it downtown for the things you need. When a baby curls a chubby arm around your neck, you can’t eat that feeling either, or buy anything with it. But what in this life means more to you than that feeling, or your freedom?”

Everett Dirksen’s final years were difficult, as he suffered from emphysema, once coughing so hard it cracked a vertebrae in his back. After hours, Senator Dirksen still clutched a highball in one hand and a cigarette in the other. Dirksen had entered Walter Reed Hospital where he had quietly undergone an operation for lung cancer and died five days later. Doctors valiantly tried to resuscitate Senator Dirksen, working on him for two hours before pronouncing the old political warrior dead.

Howard and Joy Baker joined the other mourners as Everett Dirksen’s body lay in state beneath the rotunda of the Capitol. They heard President Richard Nixon say, “Our great men are the property of the country. Everett Dirksen of Illinois was and is the common property of the 50 states.”

Senator Howard Baker made the response to President Richard Nixon’s eulogy of his father-in-law. His remarks were typical of Senator Baker, as they were brief, simple and quietly eloquent. The theme of Baker’s remarks about his late father-in-law was that Everett Dirksen was both a realist and an idealist. It was a description that Dirksen would have liked.

President Nixon gave Senator Dirksen’s widow, Louella, and the Bakers the use of Air Force One to make the trip back to Illinois with the body.

Everett Dirksen’s death was not only a personal loss to Howard Baker and his family, but it left the Republican ranks in the Senate disoriented. Despite the family ties, Howard Baker had frequently disagreed with his father-in-law. When he first arrived in the Senate, Baker had urged that freshman senators be given more important assignments, something that did not meet with the approval of Everett Dirksen.

Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania became the acting Republican leader of the United States Senate after Everett Dirksen’s death. Scott had been in Congress since 1941 and many of the younger Republican senators began to urge Howard Baker to run for Minority Leader.

Baker was hampered in his first bid to become Minority Leader due to his relative youth, as well as having been in the Senate only two years. Still, Howard Baker got strong support from many of the “Young Turks” in the Senate. Baker also had the support of some more powerful Republicans including Barry Goldwater, who had just returned to the Senate after a four-year absence.

The sixty-eight year old Hugh Scott found himself hard pressed by the forty-three year old Howard Baker. Soon there were rumors that Scott would become leader and Senator Baker would become the Minority Whip. Baker immediately denied there was any compromise. “The people I am counting on are first-ballot votes for leader. I am not running for whip,” Baker said.

Scott cobbled together an odd coalition of older conservative Republicans with liberals and moderates to edge Howard Baker 24 – 19. Baker’s relative inexperience in the Senate was the primary reason most senators gave for supporting the veteran Hugh Scott.

Two years later, Baker ran against Hugh Scott for Minority Leader yet again. Kentucky’s senior senator, John Sherman Cooper, who had been in and out of the Senate since 1946, was one of the most respected Republicans in Congress. Cooper had backed Scott in 1969, but in 1971 he generated headlines when he endorsed Baker for leader. Howard Baker lost yet again, but by a smaller margin than in 1969.

Senator Baker did not entirely give up his leadership aspirations, but it would take ten years before he managed to make his way to the top of the Senate hierarchy. Ironically, perhaps Howard Baker’s most famous assignment in the United States Senate may have been as a result of his challenge to Hugh Scott. Reputedly, Baker was placed on the “Watergate” Committee by Hugh Scott as punishment for having run against him.

Howard Baker played a pivotal role in helping the Republican tide to rise in Tennessee and it would soon rise to a peak. Governor Buford Ellington had only barely turned back a challenge inside his own party from Nashville attorney John Jay Hooker in 1966 and was not eligible to succeed himself in 1970. Tennessee’s senior U. S. senator, Albert Gore, was up for reelection as well. Despite Howard Baker’s victory in 1966, there were many Democrats in Tennessee who fully expected the Democratic nominees to win the general election.

The 1970 Republican primary for governor became a crowded affair with at least four serious candidates competing for the GOP nomination. Many Baker loyalists supported the candidacy of Knoxville attorney Claude K. Robertson, who had served as State Chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party. Nashville industrialist Maxey Jarman was well financed, while Bill Jenkins, former Speaker of the Tennessee House of Representatives, became the candidate from upper East Tennessee. Lastly, there was a young and remarkably personable dentist from Memphis, Winfield Dunn.

Republicans faced a primary in the 1970 Senate race as well. Congressman Bill Brock of Chattanooga had been considered an almost certain candidate for the last two years. Congressman Dan Kuykendall had been interested in running and had been the GOP nominee in 1964 against Senator Gore and had run a respectable race. Eventually, Kuykendall decided to seek reelection to Congress from his Memphis district and Tex Ritter entered the Republican primary.

Today, those people who recall Tex Ritter remember him as the late actor John Ritter’s father. Yet Tex Ritter had long been a popular entertainer for decades. Ritter had starred in numerous low-budget westerns from the mid 1930s until 1950. Tex Ritter continued to act occasionally and was also a country music star and sang High Noon (also known as Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darlin’), the ballad from the classic movie of the same name starring Gary Cooper.

Tex Ritter returned to Tennessee, moving to Nashville, in 1965. Ritter performed at the Grand Ol’ Opry. Ritter’s entry into the U. S. Senate race came as something of a surprise to many, as Bill Brock was considered the heavy favorite to win the GOP nomination. It was Tex Ritter who gave Senator Albert Gore the nickname, “The Old Gray Fox” of Tennessee politics.

Senator Howard Baker, keen on building the Republican Party in Tennessee, conspicuously and pointedly remained neutral in the GOP primaries. The gubernatorial contest was hard fought and Winfield Dunn emerged as the winner, running well all across the state, but winning 95% of the vote in populous Shelby County. Congressman Bill Brock crushed Tex Ritter, winning almost 75% of the vote.

Contentious primaries were hardly the property of Republicans in Tennessee. The Democrats had a bitter gubernatorial battle of their own, which was won by John Jay Hooker. Senator Albert Gore had faced his own primary, challenged by Hudley Crockett, who had been a television news anchor and later press secretary to Governor Ellington. Handsome, articulate, and folksy, Hudley Crockett gave the senator quite a scare. Gore only beat back Crockett’s challenge by 31,000 votes. Crockett had run surprisingly well in West Tennessee and the fact Senator Gore won just 51% of the vote made him an inviting target for Republicans.

Albert Gore was anything but a favorite of the Nixon White House. President Nixon had faced Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress and wanted to increase the number of Republicans in both the House and Senate. The Tennessee Senate race became a priority for the Nixon administration.

Howard Baker fell in line behind both Bill Brock and Winfield Dunn, campaigning hard for the Republican ticket. Although he was the titular leader of Tennessee Democrats, Governor Buford Ellington refused to endorse John Jay Hooker. The memory of the ferocious primary in 1966 still lingered and left the governor bitter. Nor did relatively conservative Ellington do much to help Albert Gore.

Bill Brock beat Albert Gore by more than 40,000 votes, while Winfield Dunn became the first Republican to be elected governor since 1920. Dunn beat John Jay Hooker by more than 66,000 votes.

Republican victories in statewide elections had been rare events, usually only possible when some calamity befell the Democrats but Tennessee was no longer a one party state. Howard Baker’s election to the United States Senate in 1966 had proven not to be some sort of aberration. Republicans had carried Tennessee in every presidential election since 1952 with the exception of Lyndon Johnson’s victory in 1964 when GOP nominee Barry Goldwater had suggested selling the Tennessee Valley Authority.

With the arrival of the New Year, Republicans occupied both U. S. Senate seats, the governorship and held four of the nine Congressional seats in the Tennessee delegation.

Howard Baker would have to run for reelection in 1972 and already a West Tennessee congressman was eyeing his seat longingly. That congressman was Ray Blanton and he, too, would leave his mark on Tennessee and Tennessee politics, but his legacy would be quite different from that of Howard Baker.

Stories in this Week's Focus

- The Knoxville Focus for July 14, 2025

- Publisher’s Positions

- District 1 candidates answer Focus questions

- Michigan’s Governor G. Mennen Williams

- Annual KFOA Media Day event ‘kicks off’ the season

- ‘It was tied when we started’

- The Knoxville Focus for July 7, 2025

- Publisher’s Positions

- Famous Grainger Co. Tomato Festival coming soon

- Augustus O. Stanley of Kentucky