The Senator From Wisconsin

F Ryan Duffy

Wisconsin was considered to be a solidly Republican state by the time F. Ryan Duffy waged a campaign to be elected to the United States Senate in 1932. Yet there were two strong elements of the Republican Party inside the Badger State; the GOP was divided into the progressives and the conservatives. The progressive Republicans followed the political banner of Robert M. LaFollette, known in Wisconsin as “Fighting Bob.” Highly popular, Bob LaFollette had held every office within the gift of the people of Wisconsin, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives, the governorship, and finally winning election to the U.S. Senate, where he remained until his death on June 18, 1925. His son and namesake would hold his seat in the Senate until leaving office on January 3, 1947. Eventually, the split broke the party in two, with progressives forming the Wisconsin “Progressive Party.” Democrats in the Badger State were the tail of the dog, although the divide between the Republicans gave them an opening to win statewide office.

The Great Depression altered forever the politics of the United States. Herbert Hoover had been overwhelmingly elected as president in 1928, and Republicans carried both houses of Congress. It is difficult to imagine the personal popularity of Hoover prior to the crash of the stock market. Indeed, many Americans believed Hoover to be a man of surpassing ability, one who exemplified competence as an executive. Herbert Hoover, a self-made millionaire and an engineer by profession, had won wide acclaim for helping to feed much of Europe following the catastrophic First World War. Americans regularly viewed the pitiful photographs in American newspapers of the needy European children and their mothers and fathers, who likely would have starved had it not been for the generosity of Americans in particular. Perhaps no reputation of any man who has served as President of the United States has plummeted as much as that of Herbert Hoover.

With want and hunger stalking millions of Americans by 1932, Democratic presidential nominee Franklin Roosevelt seemed like a godsend, even if he did talk about saving money and balancing budgets. The 1932 election proved to be a rare realigning election, which saw various groups move from one political party to another. Franklin Delano Roosevelt presided over a tidal wave of support of people who feared for their collective futures. Hoover and the Republicans were turned out of office. Longtime incumbents of sterling reputations and significant abilities lost, in some cases to candidates who were little more than jokes.

Wisconsin Republicans either did not see the steamroller coming or, if they did, they didn’t care. The progressives and the conservatives warred with one another inside the GOP primary. Senator John J. Blaine, a progressive, lost to challenger John B. Chapple, a newspaper publisher and conservative. Democrats had nominated F. Ryan Duffy for the U.S. Senate, and once Senator Blaine lost the election, many of his supporters refused to support the Republican nominee. Chapple cried the election of Franklin Roosevelt and F. Ryan Duffy would cause the end of the sanctity of American homes and the beginning of “Bolshevikism.” Duffy calmly told audiences it was untrue. “I’m a family man,” Duffy explained. The people of Wisconsin believed him.

A lawyer who had been vice commander of the national American Legion, Duffy ran hard for the U.S. Senate and surprised some by winning by more than 222,000 votes. Ryan Duffy went to Washington, D.C., where he became a stalwart supporter of President Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Once in Washington, D.C., Duffy was assigned a seat on the front row of the Senate, sitting to the left of the hellraiser from Louisiana, Huey P. Long. At some point, Duffy’s seatmate on the floor of the Senate was Harry S. Truman. That was the beginning of Duffy’s friendship with the Man from Missouri. Duffy wrote a series of articles about his life and remembered Huey Long as “a man who had bitter enemies and many devoted friends.” “He had a very keen mind and a prodigious memory,” Duffy recalled.

While in the U.S. Senate, Duffy was chosen to visit Flanders Field in Belgium, one of the bloody battlefields from the First World War, approximately 35 miles from Brussels. Duffy stood alongside General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, as well as several “commanding generals of the French and Belgium armies.”

Senator Duffy was one of the many Democrats who enjoyed a holiday weekend on Jefferson Island in 1937, a retreat planned for Democratic senators and congressmen to visit with President Roosevelt and heal any divisions or ill feelings. Duffy won a trapshooting match amongst the members while FDR called out to the other contestants, “How come you let a farmer from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, beat you?” That got a big laugh from those present.

Roosevelt was interested enough in Senator Duffy to give him a full-throated endorsement during his 1938 reelection campaign. Roosevelt also tried to intervene, asking the LaFollette family not to run a candidate for senator and split the liberal vote. The LaFollettes, even with the passing of “Fighting Bob,” remained powerful with Robert Jr. in the U.S. Senate and brother Phil serving as governor of Wisconsin. The LaFollettes ignored FDR’s plea and ran Herman Ekern for the Senate. Duffy and Ekern together won more votes than the winner, Alexander Wiley.

It is the nature of every pendulum to swing back and forth, and so, too, does the political pendulum. Senator Ryan Duffy had been quite fortunate to run for statewide office when Wisconsin voters wanted a change from the GOP administration and Congress. Six years later, the high tide of the New Deal and the Age of Roosevelt was ebbing. Some believed Senator Duffy was helped by the fact that the progressive Republicans had broken off from the Republicans and formed their own political party. The Progressives nominated State Attorney General Herman Ekern as their nominee for the U.S. Senate. Alexander Wiley had won the Republican nomination and was affiliated with the more conservative wing of the party. In the end, Ekern’s candidacy pulled more votes away from the candidacy of Senator Duffy than that of Wiley. Alexander Wiley won the general election with a plurality of slightly more than 47% of the ballots cast. Herman Ekern was a distant second with 25% and Senator Duffy was third with 24%, while several minor candidates divided the rest of the votes. Wisconsin would not elect another Democrat to the United States Senate until 1957, when William Proxmire won a special election to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Joe McCarthy.

Duffy left the Senate on January 3, 1939, but did not have to wait long for something to do as President Franklin Roosevelt rewarded his loyalty while acknowledging his ability by nominating the former senator to the federal bench. On June 21, 1939, the president sent the nomination of F. Ryan Duffy to serve as a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin to the Senate. As a former member of that body, his former colleagues quickly approved his nomination on June 25, 1939.

Duffy’s appointment to the bench necessitated his moving from Fond du Lac to Milwaukee. Settling into his new office, Judge Duffy discovered “a terrific backlog of untried cases.” The previous judge had been ill for three years, and the untried cases had accumulated. Duffy remembered that for the first four or five years he sat as a judge, he held court year-round without taking time off during the summer for vacations. Duffy also held court on Saturdays and sometimes resumed court after supper. F. Ryan Duffy cleared out the backlog of cases by sheer hard work. It is little wonder the administrative office of the U.S. Courts reported Duffy’s courtroom as “the busiest one-judge district court in the country.” Eventually, there would be four judges in that same district handling the load that Ryan Duffy carried alone for many years.

It was not the last time a President of the United States would appoint F. Ryan Duffy to the federal bench. On January 13, 1949, President Harry Truman nominated Duffy to serve as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh District. Once again, the Senate extended the usual senatorial courtesy given to a former member of that body, and Duffy assumed office on February 2, 1949.

Some years later, the former senator recalled that when one of the Duffy sons, Hayden, was released from the Naval Air Service a few months after the Second World War, the judge and his wife drove to Washington, D.C., to visit their daughter, Ann.

“Knowing how busy a president of the United States is,” Duffy remembered many years later, “I did not call the White House or otherwise notify the president that we were in Washington.

“We had been there three or four days when one morning the telephone rang and the president’s secretary informed me that Mrs. Duffy, I and the children were invited to come to the White House the following evening for dinner.”

Judge Duffy and his family went to the White House, where they dined on fresh salmon, which had been flown in from the West Coast earlier that day. President Truman played the piano and was introduced to “boogie-woogie” by the judge’s son, Jim. Like so many others, Duffy admired Truman for his courage and ability to make hard decisions.

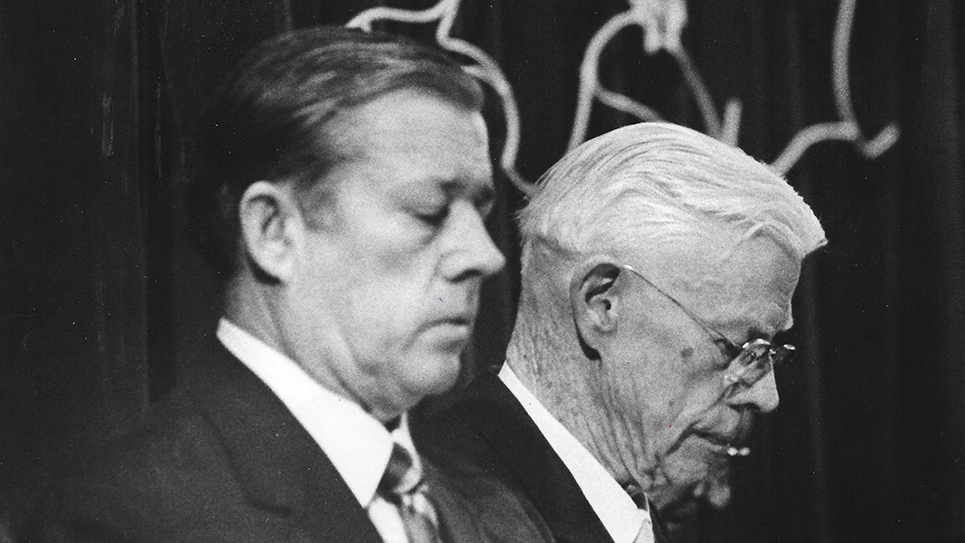

Prior to his death, Judge Duffy’s last visit to his hometown of Fond du Lac had been to donate an autographed portrait of President Truman to the local library. Nor was it the last Judge Duffy would hear from his friend from Missouri. As former Vice President John Nance Garner prepared to celebrate his ninetieth birthday, Truman telephoned Duffy, asking him to come to Independence. Truman explained they would fly from Truman’s home in Independence to Garner’s home in Uvalde, Texas. Airplane trouble delayed the flight about three hours, and Duffy recalled it was well after dark when they arrived at the small airport. To the judge’s surprise, Garner and perhaps two hundred friends were waiting to welcome the former president and his party.

Judge Duffy continued working long after most men had retired. Ryan Duffy didn’t even like the word “retirement” and bristled whenever anyone suggested he was retired. The judge always pointedly noted he still heard cases and wrote decisions and was actively serving on the bench and was most certainly not retired. F. Ryan Duffy was believed to be the oldest sitting federal judge in the country at the time of his death.

Duffy continued to hear cases and was in remarkably good health, especially for a man of his years. The judge fell and broke his hip, which kept him confined to a Milwaukee hospital for the better part of two months. Judge Duffy recovered from the required surgery, but his son noted his father couldn’t walk very well afterward. The inability to walk well finally forced Judge Duffy into retirement, which did little to improve his health. “The only reason he retired was because his walking was so bad,” F. Ryan Duffy Jr. said. “Mentally, he was excellent.”

That necessitated a sojourn in a nursing home, where the judge continued to fail. Eventually, F. Ryan Duffy lapsed into a coma, and family members gathered by his bedside while his wife, Louise, held her husband’s hand. Louise Duffy was still holding the judge’s hand when he peacefully slipped away at age 91.

In death, the judge’s son, the Reverend James Duffy, presided over the funeral of his father. Father Duffy said the judge had finally come home for the final time when his body was returned for burial in his hometown of Fond du Lac. While he only served one term in the United States Senate, F. Ryan Duffy served quite nearly 40 years as a federal judge, proving there is indeed life after politics. © 2025 Ray Hill