The Strong Man of North Carolina

F.M. Simmons

By Ray Hill

It would surprise me greatly if one reader out of a thousand knew the name of Furnifold McLendel Simmons. Long ago consigned to the pages of history, there was a time when F. M. Simmons was the most potent political figure in North Carolina. For thirty years, Simmons represented the Tarheel State in the United States Senate.

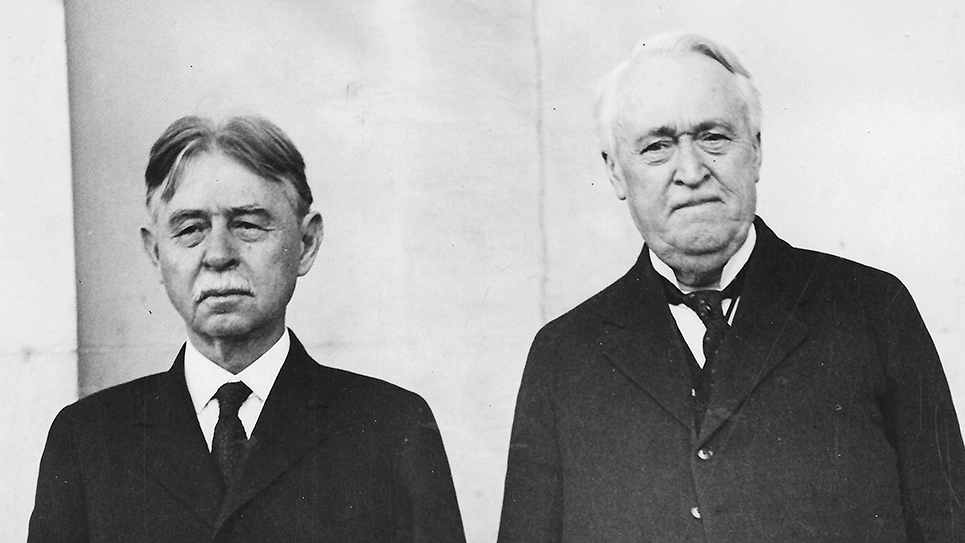

A diminutive man who seemed much bigger than he was due to an outsized reputation, Simmons parted his thick hair in the middle and sported a mustache. Known for his energy, Simmons was both an aristocrat and by profession, a country lawyer. F. M. Simmons had been born on his father’s plantation and was well educated, attending Wake Forest College, and Trinity College (which was later Duke University). At twenty-one, Simmons started practicing law in New Bern, where he lived for the remainder of his long life. At age thirty-three, Simmons was elected to Congress but served only one unremarkable term. When Simmons sought reelection in 1888, the Republican Party was united behind its candidate Henry P. Cheatham, a former slave. Cheatham beat Congressman Simmons in the general election.

In 1892, there was a wave of support in many Southern and Western states for the populist candidate for president, General James Weaver. F. M. Simmons was the chairman of North Carolina’s Democratic Party and did all he could to get Democrats in line for their own presidential nominee, Grover Cleveland. Cleveland was returned to the White House and Simmons was rewarded with an appointment as Collector of Internal Revenue for the Eastern District of North Carolina. Simmons welded together an effective political organization and was elected to the United States Senate by North Carolina’s state legislature. For the next twenty-eight years, Furnifold McLendel Simmons was the undisputed political overlord for the Tarheel State. Only when Simmons balked at supporting the presidential candidacy of Alfred E. Smith, the Catholic and dripping “wet” governor of New York, was the senator’s power broken.

After Simmons had resigned the chairmanship of North Carolina’s Democratic Party, Populists and Republicans began to make gains. Within four short years, neither U. S. senator was a Democrat; North Carolina was represented in the Senate by a Republican and a Populist. The Populists and Republicans, Black and White, formed a combine and called themselves “fusionists.” The combination captured not only the state legislature but numerous other local offices as well.

North Carolina Democrats once again turned to F. M. Simmons, begging him to accept the chairmanship of their party. Simmons reluctantly agreed and helped to organize the members of his party. Simmons used every means available to elect a majority of Democrats to the state legislature. Simmons sponsored an amendment to North Carolina’s state Constitution to disenfranchise Black voters, who almost unanimously voted Republican. Simmons won a primary in 1900 and was subsequently elected to the United States Senate by the legislature over the incumbent, Marion Butler, who had been elected as a Populist.

While Simmons’ single term in the House of Representatives was modest enough, Simmons became a figure in the Senate to reckon with. Simmons was considered one of the leading members of the U. S. Senate and one of that body’s most influential senators. Even Republicans respected Simmons, who remained active and busy throughout his long tenure in the Senate.

For the first six years of his senatorship, Simmons served in the dual role of chairman of North Carolina’s Democratic Party. Simmons finally relinquished the chairmanship following his reelection in 1907. The legend of the Simmons political machine continued to grow throughout his Washington service. Senator Simmons was shrewd in his use of political patronage and deft in his supporters backing a succession of successful gubernatorial candidates. North Carolina did not then allow governors to serve two consecutive terms; most served four years and then went on to other pursuits or back to their chosen professions.

Once in the Senate, F. M. Simmons worked hard to ensure that his state received its fair share of public favors, usually while a Republican occupied the White House. When Woodrow Wilson won the 1912 election and Simmons ascended to the chairmanship of the Senate Finance Committee, Simmons reached the apex of his usefulness to the people of North Carolina, although he continued to be highly influential inside the Senate. F. M. Simmons did much to improve the ports and waterways of the Tarheel State and continuously carefully tended to the many ordinary chores required of a long-serving U. S. senator. Simmons answered his mail, worked hard to deliver services to his people, and skillfully distributed the patronage appointments available to him to his supporters and friends.

Due to his presiding over a political machine that had proven itself to function smoothly and effectively, Senator Simmons was not usually seriously opposed inside the Democratic primary. That changed in 1912 when Simmons faced three formidable challengers in the primary, including two former governors, William W. Kitchin and Charles B. Aycock. Former Governor Aycock would have been a threat to Senator Simmons, but he died suddenly before the primary. Simmons fended off his opponents and easily won reelection as Woodrow Wilson became the first Democrat since Grover Cleveland to occupy the White House. Simmons became chairman of the Senate’s powerful Finance Committee and was a sponsor of the Underwood-Simmons Tariff Bill, which helped to finance the First World War through bond issues and higher taxes on “incomes, corporations and excess profits.”

F. M. Simmons was considered a heavy favorite for his expected 1930 reelection campaign. There were rumblings from those Democrats who chaffed under the rule of the Simmons machine, but it was Simmons himself who brought about his own political fall. A dedicated prohibitionist, Senator Simmons could not countenance the presidential candidacy of Al Smith. Unlike many Southerners, the senator was not especially bothered by Smith’s religion, but the New York governor’s views on prohibition, immigration and urbanism were diametrically opposed to those of F. M. Simmons. Simmons was also highly suspicious of Tammany Hall and Smith’s proud membership in that notorious political organization.

Senator Simmons could have maintained the “golden silence” adopted later by Virginia’s Harry Byrd, but instead he refused to support or vote for his party’s presidential nominee. Simmons was also the Democratic National Committeeman from North Carolina at the time and the senator resigned his post in protest when Al Smith was nominated for the presidency.

North Carolina’s healthy minority of Republicans were solidly for their own nominee, Herbert Hoover, and there were enough Democrats who followed the lead of Senator Simmons and bolted their own party to carry the state for Hoover.

Oftentimes an aging incumbent seems not to realize change comes whether one likes it or not. The 74-year-old Simmons didn’t cultivate younger members of his own party as they rose through the political ranks. The younger folks didn’t know Simmons well and had few or no ties to the senator; nor did they have any personal loyalty to the old warrior. Time had also thinned the ranks of his own supporters and friends. Age, illness and death had culled many of his loyal followers from the voting rolls. Josiah W. Bailey, who had run a strong but losing campaign for governor previously, challenged Simmons inside the Democratic primary. Bailey excoriated the senator for North Carolina having fallen into the Republican column in 1928. Josiah Bailey was also significantly aided in his candidacy against Simmons by having the support of Governor O. Max Gardner, who was well on his way to becoming the new strong man of North Carolina’s Democratic Party. Another factor that hurt Senator Simmons at the polls was the advent of the Great Depression and the Hoover administration’s response to it. Millions of people believe President Hoover and his administration had failed them. In North Carolina, tens of thousands of people faulted F. M. Simmons for having supported Herbert Hoover over Al Smith.

The senator had never given his political enemies any quarter and he asked for none. Simmons was utterly unrepentant, convinced he had taken the only course available to him. North Carolina Democrats disagreed and Simmons carried only sixteen of the Tarheel State’s one hundred counties.

Some years later, W. T. Bost wrote in a newspaper column noting Simmons had taken his political extinction “with great dignity.” “He was bigger in it than he ever was in the succession of victories won at the polls and in the Congress.” Bost praised the former senator for his ability to “absorb a beating without bitterness.”

After completing his service in the United States Senate, Furnifold M. Simmons went home to New Bern, where he lived out his remaining days in retirement. Simmons addressed his apostasy with his biographer, admitting, “I may have erred at times, but my intentions have been honorable. . .” To the very end, Simmons was firmly convinced he had followed the right course in opposing the election of Al Smith. The former senator pointed to a speech he had given at the time saying he would willingly surrender his senatorial toga and retire to private life “rather than vote for Al Smith.”

“To this day I have never regretted in the slightest this decision, although I was the only Democrat in either house of Congress to pursue that course. I have never apologized for it, and I have lived to have the satisfaction of knowing that if I needed any vindication, Al Smith’s course since then has furnished that vindication,” Simmons told his biographer.

By the time he died, even those who disagreed most bitterly with the former senator did not doubt his sincere conviction prevented him from supporting Al Smith.

The ex-senator’s retirement years were full of challenges that might well have taken a lesser man down. Simmons had lost considerable money during the Great Depression like so many others and was forced into bankruptcy. Ill health plagued the former senator, yet Simmons told friends those were the happiest days of his life until his wife died in 1938. Although entirely out of politics, Simmons watched developments in Washington and approved much of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The former senator was especially in favor of the New Deal’s agricultural program.

Furnifold M. Simmons died on April 30, 1940, at age eighty-six. The Winston-Salem Journal published an editorial citing the senator’s many accomplishments on behalf of North Carolina, noted his leadership of the Tarheel State’s Democratic Party for forty years and concluded “Our people are more indebted to F. M. Simmons than to any other man.” The Journal opined “Simmons found the supreme happiness that comes to a man who lives with a conscience that has refused to sacrifice principle for expediency.”

The Greensboro Daily News editorialized that former Senator Simmons deserved praise but was also realistic about the machine’s methods in North Carolina. The editorial acknowledged the restoration of the Democratic Party’s rule “was accomplished by ruthless methods which North Carolinians have properly come to disavow.” The newspaper also admitted “that these methods, including resort to prejudices” had been employed by the Democratic machine.

The Asheville Citizen-Times published its own editorial about F. M. Simmons and his service to North Carolina. That newspaper likely provided the best summation of the senator’s long and fruitful career. “Furnifold M. Simmons was a political boss. There should be no disguising of that fact. But he never wielded his power sordidly or corruptly. He believed in his party and his state and tried earnestly and ably to advance their interests,” the editorial concluded.

Former U.S. Senator Furnifold M. Simmons’ earthly remains were put to peace in a simple and dignified service. Tributes poured in from all over North Carolina from the mighty and the church was filled to capacity with the old friends who had formed the core of the senator’s once vaunted political machine. F. M. Simmons was laid to rest in the inner banks of his beloved New Bern.

© 2024 Ray Hill