When the Mountain State had Three Senators

“History is not the past but a map of the past, drawn from a particular point of view, to be useful to the modern traveler.” Historian Henry Glassie.

By Ray Hill

Sorting through history is rather like finding an endless trove of buried treasure. There is always something to turn up and over. One of the more unusual historical altercations came from an episode when two political factions warred over a seat in the United States Senate. There is nothing especially unusual about that; what is unusual about this particular event is the fact two different governors appointed two different senators. Unlike the House of Representatives where a special election is called by the governor, when a member of the United States Senate dies or resigns from office, the governor makes an appointment to fill the vacancy. The appointee serves until the next regular election and a successor (which can also be the appointee should he/she run and win) is duly elected.

The politics of West Virginia has been as wild and wonderful as its own state motto. Largely Republican before the advent of the Great Depression, the Democrats became the dominant party with the 1932 election. As is oftentimes the case, with success came division. The Democratic Party of West Virginia became sharply divided. The factions could be most easily labeled as the “statehouse” Democrats and the “federal” Democrats. The “federal” faction was led by the most colorful and arguably, the most popular Democrat in the state: Matthew Mansfield Neely. Neely was an amazing character and made more and better comebacks than even Lazarus. Matthew Neely had a propensity of being elected and then losing an election and coming back from defeat. Neely had been elected to Congress in a 1913 special election when incumbent congressman John W. Davis had resigned to accept an appointment as ambassador to the Court of St. James. Neely was routinely reelected every two years until the Republican tidal wave of 1920, which swept Neely and the Democrats out of office. Matt Neely aimed higher two years later and beat Senator Howard Sutherland, a Republican, in the 1922 election. Senator Neely was unseated by GOP Governor Henry Hatfield six years later in 1928. Undeterred, Neely came roaring back to win the seat of retiring Senator Guy Goff in 1930. Neely won by the greatest majority up to that point of any candidate in West Virginia history seeking a Senate seat.

It was Neely’s insistence in meddling in the 1934 Democratic primary to choose an opponent for Senator Hatfield that his conflict with the statehouse faction came to a head. Clem Shaver, a former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, was a candidate for the Democratic nomination and was politically obnoxious to Neely. Senator Neely opted to back the candidacy of Rush D. Holt, a twenty-nine-year-old state legislator. No politician in West Virginia had more or better ties to the powerful organized labor movement in the Mountain State than Matthew Neely. At Neely’s urging, the United Mine Workers and other labor groups coalesced behind the candidacy of Rush Holt, who won the nomination. Holt went on to win the general election and had to wait six months before he could take the oath of office, as he was not yet the required age of thirty under the Constitution.

The statehouse faction was led by H. Guy Kump, who had been elected governor in 1932. Kump was a popular figure, leading the state during the Depression. At the time, West Virginia governors were barred from seeking consecutive terms. Kump backed his attorney general, Homer Holt (no relation to Rush Holt), to succeed him in the 1936 election. Homer won the Democratic nomination and election.

Neely’s friendship, political and otherwise, with Rush Holt came to an abrupt and spectacular end over patronage disagreements. By 1936 when Neely was running for reelection to the Senate, he referred to his junior colleague as a “sewer rat” among other lively epithets. With Senator Holt becoming pointedly isolationist in outlook and a foe of the Roosevelt administration, all federal patronage in the state was in Neely’s hands. Yet the statehouse Democrats controlled all of the resources of state government and were building up a formidable machine, which was less friendly to the national administration and more conservative generally.

Senator Neely realized a showdown would come between the two factions, which were struggling for dominance in the state. Neely announced he would back a challenger for the Democratic nomination for governor in 1940 against Carl Andrews, the favorite of the statehouse machine. One by one, Neely eliminated every prospective candidate who sought the endorsement of the senator’s federal faction. Only one candidate could meet the exacting criteria Senator Neely posed for the governorship: Neely himself.

After a bitter and savagely fought campaign for the Democratic nomination, Neely beat Carl Andrews. It was not the last pitched battle fought between the two factions. Another had been fought in the 1940 Democratic primary for the United States Senate where Senator Rush Holt was seeking a second term. Former Governor Guy Kump was the statehouse candidate for the nomination, while local Judge Harley Kilgore was Neely’s candidate. Kilgore won, while Kump ran second and Holt trailed in third place. Both Neely and Kilgore won the general election with Franklin Roosevelt at the top of the ticket.

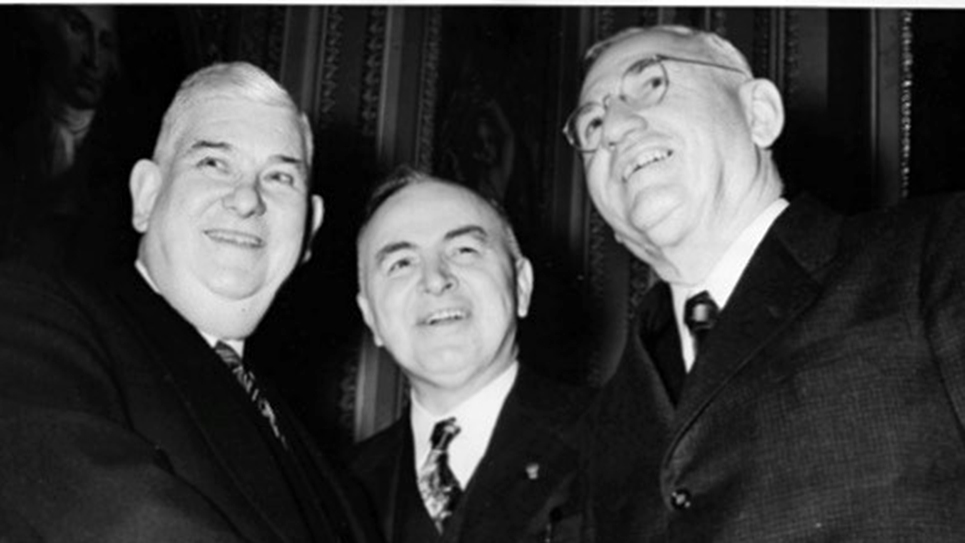

The very first dilemma faced by Matthew Neely was resigning his seat in the United States Senate. Both Governor Holt and Neely appointed men to the U. S. Senate. Governor Holt’s appointee was Clarence Martin, a respected attorney and former president of the National Bar Association.

Neely, never one to shy away from the bold or flamboyant, took the oath of office no less than three times, anticipating appointing his own successor to the United States Senate. The first oath occurred “instantly after midnight” on January 13, 1941, and was administered by John Kenna, a justice of the state Supreme Court. Neely’s signed oath of office was filed with William S. O’Brien, West Virginia Secretary of State, by Arthur B. Koontz, the Democratic National Committeeman from the Mountain State, and Hale Watkins, Chairman of the state Democratic Party. Evidently, Matt Neely kept much of West Virginia’s political establishment up late that night.

Two hours later, Governor M. M. Neely announced he had appointed Dr. Joseph Rosier to the U. S. Senate. Rosier was a resident of Neely’s home city of Fairmont and a well-regarded educator and president of the Fairmont State Teacher’s College. Knowing his way around Washington, D.C., Governor Neely sent a telegram to Edwin A. Halsey, Secretary of the United States Senate, informing him of Dr. Rosier’s appointment. Neely’s telegram to Halsey also mentioned he had tendered his own resignation from the United States Senate “precisely at midnight” on January 12. “Dr. Rosier, who is one of West Virginia’s most illustrious men will with his duly executed credentials, promptly present himself to you for the purpose of taking the required oath of office. . .”

At the same time, retiring Governor Homer Holt appeared in the office of Secretary of State O’Brien to “reaffirm” his own appointment of Clarence E. Martin. A very able attorney (he would go on to become general counsel for Union Carbide), Holt’s appointment of Martin was made “at the first moment of this 13th day of January, 1941.”

In between receiving outgoing Governor Homer Holt and accepting the Rosier appointment, Secretary of State William S. O’Brien took his own oath of office for the new four-year term to which he had been elected in 1940 “in the event any question should arise as to the proceedings tonight.”

Neely took the oath of office once again in his study at the governor’s mansion and again for the third time at the official inaugural ceremonies. Governor Neely exuded confidence, telling newsmen he was fully confident his own appointee would be seated as the senator from West Virginia.

Matthew M. Neely was a wily politician, and one didn’t survive in wild and wooly West Virginia, as he did for generations, without knowing something about practical politics. Neely realized the United States Senate retained the sole authority for determining its own membership. The new governor had just thrown a political hot potato in the lap of his one-time colleagues. Neely’s resignation also elevated freshman Harley Kilgore to the status of West Virginia’s senior U.S. senator.

As the U.S. Senate untangled and argued over the merits of which appointee had the legal right to serve as a member of that body, an exasperated Alben Barkley, the Majority Leader of the Senate, growled the entire kerfuffle was at the very least unseemly, if not indecent. In any legislative body, whether it is local or federal, relationships matter. That between Alben Barkley and Matthew Neely was somewhat strained. Barkley had not entirely forgiven and had certainly not forgotten the West Virginian having inferred the Majority leader’s opposition to a bill he had sponsored to outlaw the “block booking” of movies had been for financial gain. That was the worst kind of insult one could level at a colleague in the Senate.

Naturally, the politics of the two prospective senators mattered to the senators considering the legal claims of the appointees. While both were Democrats, Dr. Joseph Rosier was acknowledged to be a strong supporter of Franklin Roosevelt and his administration, while Clarence Martin was thought to be more conservative.

It took months for the Senate to hold hearings and listen to the arguments of both Martin and Rosier and their respective claims to the seat to which each man had been appointed. After winding its way through the appropriate committee, senators took four days in listening to the facts of the case on the floor of the Senate. Senators discussed and argued the various precedents, while others debated the facts surrounding each appointment and the law involved. It should surprise exactly no one that there was maneuvering behind the scenes. The Roosevelt administration exerted all of the influence it could summon on behalf of Dr. Joseph Rosier.

Clarence Martin had his own supporters and commanded backing from conservative Democrats and many Republicans inside the Senate. Many of Martin’s colleagues from the American Bar Association lobbied hard for his being seated in the Senate.

Whatever his personal feelings about Matt Neely, Alben Barkley did his duty as the leader of his president’s party in the United States Senate. Barkley argued hard on behalf of seating Joseph Rosier. If the spectacle was indeed unseemly and indecent, Barkley said it was the fault of Homer Holt, the outgoing governor of West Virginia and not that of Neely.

The Senate was sharply divided and the vote was close. Clarence E. Martin was denied a seat in the United States Senate by a vote of 40 – 38. Dr. Joseph Rosier, a quiet, white-haired professional educator who had been a faithful supporter of Matthew Neely, took the oath of office.

Matthew Neely had gotten his way and it was common knowledge in the Mountain State that Joseph Rosier was merely a placeholder. As Governor Neely fired those Democrats from state jobs who had been aligned with the administrations of Guy Kump and Homer Holt and replaced them with his own followers, it was generally believed he would try to regain his seat in the Senate in 1942.

That proved to be the case and having merged the federal and statehouse factions, Neely easily turned aside a determined challenge inside the Democratic primary by Guy Kump. Yet the people of West Virginia were not thrilled by Matt Neely’s skipping from one office to another at his own whim. Neely lost the general election to an unknown Republican, Chapman Revercomb.

The verbose Neely, when asked about his loss, snapped, “A fatalistic philosopher once said that on election day the American people have the right to do anything they damned please. Recent returns from the political front preclude the possibility of refuting this assertion.”