Matthew Mansfield Neely may be the most resilient politician in our nation’s history. Perhaps the only person in recorded history who made a better comeback than Neely was Lazarus and while Lazarus came back from the dead only once, Neely came back from political death repeatedly.

M. M. Neely was born November 9, 1874, in Doddridge County, West Virginia. Neely attended Salem College but left before completing his degree, although he did earn a law degree later from West Virginia University. Neely was practicing his profession in Fairmont, West Virginia when he was elected Mayor of his home city. When President Woodrow Wilson appointed John W. Davis to be Solicitor General of the United States in 1913, Matthew Neely ran for and won Davis’s old Congressional seat. Neely was reelected to Congress in 1914, 1916 and 1918. Neely’s political fortunes suffered from the increasing unpopularity of President Wilson and the Republican tide of 1920. Neely lost his seat to a Republican but immediately set out to win a seat in the United States Senate in 1922. Neely challenged incumbent Senator Howard Sutherland and won. Senator Neely had the misfortune to be a candidate in yet another Republican year and lost his reelection bid in 1928 to popular former Governor Henry Hatfield.

Again undaunted, Neely resolved to run for West Virginia’s other Senate seat in 1930. The Republican incumbent, Guy Goff, opted not to run and Neely won a smashing victory. From that point on Matthew M. Neely’s political fortunes would rise and fall, but he remained a genuine force to be reckoned with in every political campaign until his death.

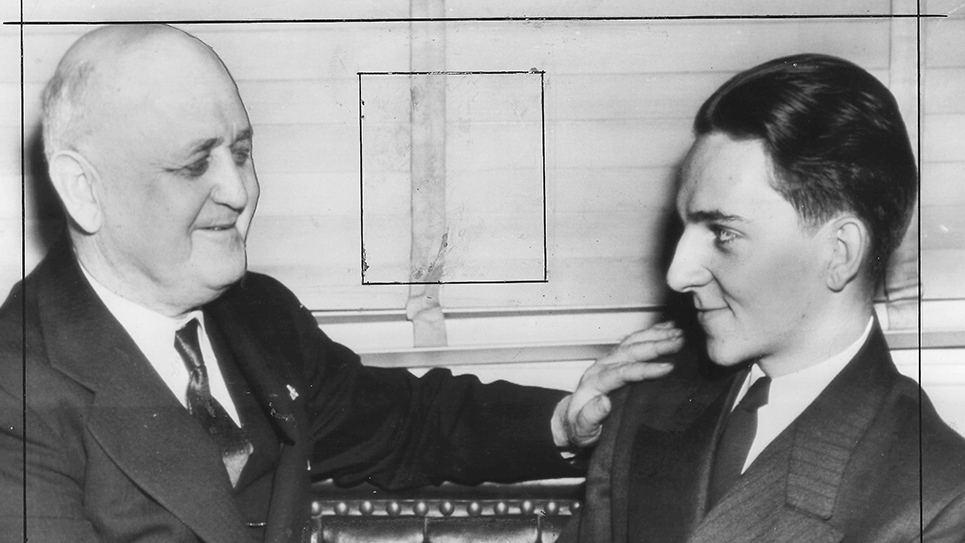

Neely was an old-fashioned orator, speaking in a flowery language that was likely even outdated for the time. Neely had a near-photographic memory and would deliver his orations after having read them only once or twice. Oddly, for a successful politician, Neely disliked crowds and it was not uncommon for Neely to give an impressive speech, only to disappear just as soon as he left the platform. Matthew Neely was also something of a dandy, always impeccably and immaculately dressed.

With the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the politics of West Virginia changed dramatically. Prior to the Great Depression and Roosevelt, West Virginia had been more often than not a reliably Republican state. Following FDR’s election, it became solidly Democratic in its voting habits. Along with Franklin Roosevelt, West Virginia had elected a new Democratic governor, H. Guy Kump. Governor Kump proved to be a highly effective and talented administrator, but he was far more conservative than the liberal Matthew M. Neely. Neely promoted the candidacy of Rush D. Holt against his Senate colleague and rival Dr. Henry Hatfield in 1934. Holt, then only twenty-nine years old, faced a crowded primary field composed of other ambitious and more experienced Democrats. With Neely’s help and that of organized labor, Holt was nominated and defeated Senator Hatfield, despite the fact he would not meet the constitutional age requirement of thirty years until the following summer.

Senator Neely soon found himself at odds with the state administration and Governor Kump managed to handpick his successor, Attorney General Homer Holt, another conservative Democrat. Neely was soon bitterly disappointed with his protégé Rush Holt when the young man was infuriated by his inability to get more patronage from the Roosevelt administration. Federal patronage in West Virginia was largely in the hands of Matthew M. Neely and Holt launched a bitter and personal attack on his senior colleague. Holt’s frustration with the Roosevelt administration caused him to become one of the least predictable opponents of FDR in the Congress and he was soon one of the leading voices of the isolationist movement in Congress as well.

Neely, whose command of the English language was second to none, fought back and in one speech denounced Senator Holt and perhaps the nicest thing he said about his young colleague was that Holt was a “sewer rat”. Senator Neely was facing opposition from both the state administration and Rush Holt. Neely was the recognized leader of the “Federal faction”, which was stoutly opposed by the “state faction”. Despite the opposition to Neely, he was reelected by a tremendous majority in 1936 even with Senator Holt actively stumping against him.

Few could use the dramatic gesture as well as Matthew Neely and he decided to take the fight to his political opponents in a preemptive strike. After having publicly mused he would support any candidate who supported Franklin Roosevelt for the West Virginia governorship in 1940, Neely eliminated the various possibilities one by one. Neely finally determined he would be the strongest candidate for governor in 1940. Neely announced he was running for governor and helped to recruit a little-known local judge, Harley M. Kilgore to challenge Rush Holt in the Democratic primary. The threat in the Senate race was especially dire, as former Governor Guy Kump had decided to enter the race. Kump sponsored a candidate against Neely in the gubernatorial primary while Neely returned the compliment in the Senate race. Neely easily defeated his opponent and had the satisfaction of seeing Harley Kilgore not only win the senatorial nomination but watching Rush Holt run a poor third behind former Governor Kump. Both Neely and Kilgore ran with Franklin Roosevelt, seeking his third term in 1940. The entire Democratic ticket in West Virginia was successful and Governor Neely soon wiped out those state employees who owed their allegiance to the state machine, replacing them with Neely loyalists.

Matthew M. Neely took the oath of office as governor no less than three times, as he proposed to name his own successor to his seat in the United States Senate. Not to be outdone, Governor Homer Holt insisted he had the right to appoint Neely’s successor. Holt appointed Clarence Martin, a conservative and a former president of the American Bar Association. Neely appointed Dr. Joseph Rosier, the long-time President of the Teacher’s College in his home city of Fairmont. The U. S. Senate spent months determining which appointee was the legitimate member, finally seating Rosier.

By 1942, Neely had eliminated most of his serious opposition inside his own party and was intent upon returning to his first love, the United States Senate. Former Governor H. Guy Kump again sought the Democratic nomination and waged a bitter primary battle with Neely and while losing, Kump inflicted enough damage on Neely to cause a very surprising result in November. Governor Neely was facing Chapman Revercomb in the general election and West Virginia had not elected any member of the GOP to statewide office since 1928. Neely confidently expected to be elected in 1942, but the war was not going well for the allies and many Kump Democrats exacted their revenge by quietly supporting Revercomb. Neely was astonished to lose to Revercomb decisively.

Neely’s statement on his defeat was characteristic: “A fatalistic philosopher once said that on election day the American people have the right to do anything they damned please. Recent returns from the political front preclude the possibility of refuting this assertion.”

Neely unhappily remained governor until 1944 and later referred to his decision to seek the governorship as the greatest mistake of his long career. Neely would invite friends to come and visit him at the Governor’s Mansion and oftentimes referred to his “confinement” in the state house. West Virginia did not permit its governors to seek a second consecutive term and Neely disliked private life. He concluded he would seek election to his old Congressional seat, which was then occupied by a Republican. Neely, again running with an ailing FDR who was seeking his fourth term, defeated GOP Congressman A. C. Schiffler. At seventy years of age, Matthew M. Neely returned to Congress in 1945 as a freshman legislator.

Neely resumed his crusade for Federal funding for cancer research. It was a topic dear to his heart, as Neely had lost several fingers on one hand to cancer. Neely made impassioned pleas for funding to find a cure for cancer. Neely had been one of the original Congressional sponsors of the National Cancer Institute Act and throughout the remainder of his career was an unwavering proponent of more government aid to find a cure for cancer.

Neely sought reelection to Congress in 1946 but was upset by yet another wave of votes for Republicans across the country. Neely returned to his law practice in Fairmont and despite being seventy-three years old, made plans to win back his old Senate seat in 1948. Neely had the express satisfaction of defeating two former antagonists that year; he dispatched former Senator Rush Holt easily in the primary and went on to defeat incumbent Republican Chapman Revercomb by a large majority. It was Rush Holt’s last campaign as a Democrat; he became a Republican and lost a Congressional race in 1950 and was only narrowly defeated for governor in 1952. Neely’s intense dislike for his old opponent faded away when Rush Holt was stricken with cancer. Neely quietly made it possible for Holt to enter a facility for treatment.

Matthew Neely returned to the United States Senate at age seventy-four and remained there for the rest of his life. He was reelected in 1954 at age eighty, but he was not to finish his term. Neely’s most relentless opponent of all, cancer, returned in 1957. It was to be Neely’s last battle and while the old warrior would make occasional appearances on the Senate floor, especially when Democratic Leader Lyndon Johnson feared a close vote, he spent increasingly more time hospitalized. When Neely entered the Senate Chamber for the last time, he was still impeccably dressed, but quite frail and confined to a wheelchair.

Matthew M. Neely lost his final struggle on January 18, 1958, finally succumbing to cancer. Neely was forthright in his politics and while loved and admired by many, including organized labor, he was cordially disliked by the captains of industry. Once, after an appallingly inappropriate introduction at an event sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce, Neely got to his feet and glared at the Master of Ceremonies and started his speech by snapping, “And the same to you, sir!”

As we approach the holidays, it seems appropriate to quote the old West Virginian who was equally adept at thundering from the mountain and cooing soft words that conjured the warmest of feelings. Governor Matthew Mansfield Neely issued a 1943 holiday message to West Virginians fighting across the globe during World War II.

“The Christmas dinner will not be sumptuous enough, the snow will not be white enough, the sun will not be bright enough, to tempt us to forget you, or cease to regret that you are far away on this most important holiday of the year.”

It was vintage Neely and there will never be another like him.

Stories in this Week's Focus

- The Knoxville Focus for July 22, 2024

- Publisher’s Positions

- Wow! Helton makes himself at home

- Robert L. Ramsay of West Virginia

- Lane has all the keys to use at Central now

- Dogwood Arts announces large-scale mural project in North Knoxville

- The Knoxville Focus for July 15, 2024

- Are the Liberal Media and Elites Abandoning Biden?

- Helton had ‘it’ and more to get to Cooperstown

- Bluegrass Statesman: Marvel M. Logan of Kentucky