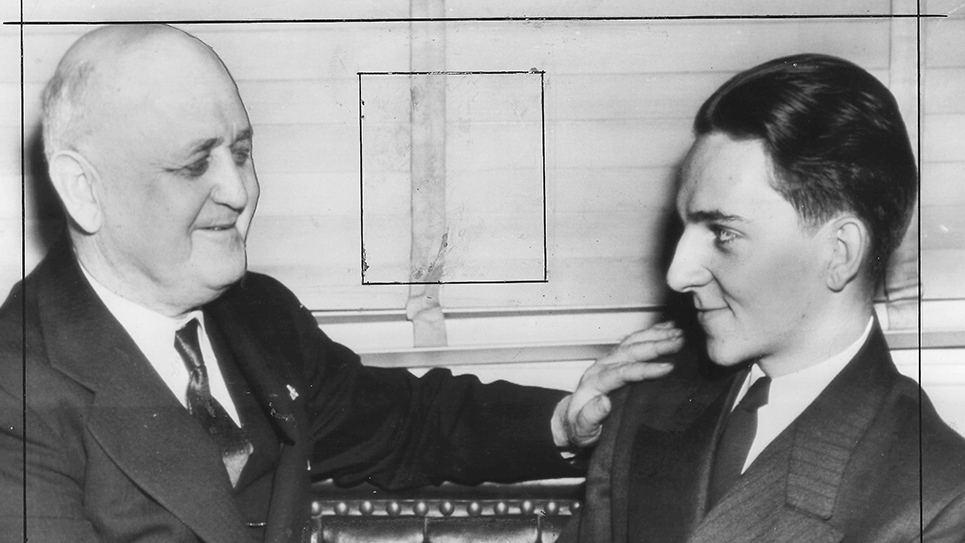

From the author’s personal collection.

Senator & Mrs. William E. Borah dressed for a night out in Washington society.

William Edgar Borah was one of the most celebrated members of the United States Senate during his time. Enormously popular in his state of Idaho, Borah was an impressive orator, regularly filling the Senate galleries when he spoke and his speeches were unusual in that his oratory could move colleagues to actually change their votes.

Borah was born on June 29, 1865 in Illinois, where he spent his childhood. Illness forced Borah to leave his studies at the University of Kansas, although he did manage to earn a law degree and practiced for a brief time in a tiny Kansas town. William Borah moved west and settled in Boise, Idaho in 1890 where he soon became one of the leading lawyers in the state. Borah possessed a remarkable ability to sway jurors with his oratory, as he would in the United States Senate. Bill Borah would also participate in some of the most famous, if not notorious, legal cases in Idaho.

Borah’s legal prominence also aided his political ambitions and he was a candidate for the United States Senate in 1902 at a time when state legislatures still elected senators. Borah was unsuccessful in 1902, but tried again in 1906 and was elected. Before leaving for Washington, D. C. he was named as the special prosecuting attorney in what would become a legendary trial in Idaho. Borah was prosecuting a group of men affiliated with organized labor who had allegedly been responsible for murdering a former governor of Idaho, Frank Steunenberg. The defense counsel was no less than Clarence Darrow, the renowned “attorney for the damned”. Oddly, Borah was himself indicted by a jury in a fraud scheme as he was prosecuting “Big Bill” Hagood and his accused fellow conspirators.

Steunenberg had been killed by a homemade bomb at his home. The former governor had been considered an opponent of the Western Miners’ Federation and the men accused of the crime were members of the WMF.

William Borah was disappointed by the verdict of the trial, as Hagood and another accused co-conspirator were acquitted. Borah himself survived the fraud charges, which many considered to be preposterous. Borah soon departed to take his seat in the United States Senate, accompanied by his wife, Mary, who was the daughter of a former governor of Idaho. Mary McConnell Borah became a fixture in Washington society and was fondly known as “Little Borah”.

The Borah marriage became the subject of much discussion, especially following Senator Borah’s death. The couple was childless and the senator was apparently highly attractive to other women. One such woman was the doyenne of Washington society, Alice Roosevelt Longworth. Famous for her tart tongue and snide bon mots, Alice was the daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt and the wife of Ohio Republican Congressman Nicholas Longworth, who was also Speaker of the House. Alice Longworth was forty-one years old when she announced she was pregnant. Speaker Longworth was delighted, but Paulina Longworth was quite likely the illegitimate daughter of Senator William E. Borah. Supposedly, Alice Roosevelt Longworth herself later admitted Paulina was Borah’s daughter.

Borah was also reputed to be the paramour of “Cissy” Patterson, the publisher of the Washington Times. Patterson and Mrs. Longworth evidently engaged in a few skirmishes over the affections of Senator Borah, with Cissy once asking Alice to look for her missing undergarments in a chandelier.

Despite Senator Borah’s extramarital activities, he remained highly popular in Idaho. He was reelected by the legislature in 1912, but would prove to be equally popular with the people of Idaho in subsequent elections.

Although a Republican, Borah quickly gained a reputation for putting principle above party. Borah was also perceived by many to have such a contrary nature the taciturn President Calvin Coolidge made a comment much quoted about the Idaho senator. Borah was an enthusiast of horseback riding and would regularly ride his horse through Washington’s Rock Creek Park. Coolidge, no admirer of Borah, wondered how Borah could bring himself to travel in the same direction as the horse.

Senator Borah was bitterly opposed to President Woodrow Wilson’s effort to bring America into the League of Nations. Throughout his entire Senate career, Borah would oppose any legislation or effort he believe would involve America in the affairs of other countries. When President Wilson began a tour of the United States to personally make his case for American participation in the League of Nations, Borah and California Senator Hiram Johnson followed in his wake, speaking against the U.S. entering the League.

Borah was a “progressive” Republican, as were many of his colleagues from the American West, yet the contrary Idahoan was a strong supporter of individual state sovereignty. Borah opposed efforts to make lynching a Federal crime, as he believed it was not constitutional.

By 1925, Borah was the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, where he advocated recognition of the Soviet government. Since the fall of the Tsar in 1917 and the bloody revolution by the Bolsheviks, the United States government had refused to recognize the Communists as the legitimate government of Russia.

Borah proved yet again he was not bound by party ties when he helped to expose the scandals in the administration of President Warren G. Harding. Despite his having no affection for the Idaho senator, President Calvin Coolidge recognized Borah’s vote getting potential and reportedly offered Borah a place on the Republican ticket in 1924. Borah reputedly loftily replied, “In which place?”

Senator Borah, unlike some of his progressive colleagues, did not bolt the party, but he refused to endorse President Herbert Hoover’s reelection in 1932. Borah had been unhappy with the Hoover administration and favored more proactive measures to address the effects of the Great Depression. The unpredictable Borah lent his support to some aspects of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, but was a powerful voice in opposition to other measures.

Borah had flirted with having presidential aspirations throughout much of his career and in 1936 became an active candidate for the GOP nomination. President Roosevelt himself seemed to respect Borah, but considered him no threat as FDR realized Borah would encounter stiff opposition from the more conservative elements of the Republican Party. Roosevelt’s prescience proved to be accurate and despite having personally campaigned in several primaries, Borah managed only to get a handful of delegates. Ultimately, Borah again refused to endorse the Republican nominee, a risky proposition when he finally faced a difficult reelection campaign that same year.

Three-term Governor C. Ben Ross had been a popular chief executive and was running against Borah in what would be one of the most Democratic years in history. Franklin Roosevelt, himself a candidate for reelection, visited Idaho, only to be greeted personally by Senator William E. Borah. To the horror of Idaho Democrats, it became readily apparent FDR had no objection to Borah being reelected. Borah crushed Ross at the polls, winning a remarkable victory as Republicans across the country lost to Democratic challengers.

Roosevelt may have later regretted not having tried to dislodge Borah as the Idaho senator proved to be an immovable object as FDR tried to navigate the perilous political waters of foreign affairs as war loomed in Europe. In 1939, Borah attended a meeting with President Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull and several other senators. As Hull patiently warned of war and provided secret information coming from U. S. embassies in Europe, Borah openly scoffed.

Cordell Hull possessed a Tennessee temper and snapped he wished Borah would visit the State Department and read some of the dispatches reaching him. Never one to be easily moved from his position, Borah retorted, “I don’t give a damn about your dispatches.”

Borah went on to tell an astonished Hull and President Roosevelt, he, too, had his own sources of information and he did not believe there would be any war.

Whether or not Borah was embarrassed when German dictator Adolf Hitler’s army invaded Poland, causing France and Great Britain to declare war on Nazi Germany, is not known.

Borah never lived to see the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Empire. On January 16, 1940, Borah stopped briefly early that morning to chat with his wife, Mary. He urged her to see a doctor as she had been sneezing and went into the bathroom to shower. When Borah did not emerge from the bathroom for what seemed to be a very long time, Mary Borah found the senator lying on the floor unconscious and his head bloody. A frantic Mrs. Borah summoned a doctor, who informed her that her husband had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Evidently Borah had struck his head when falling, causing deep cut along his temple. Only the day before Borah had visited his own physician who had declared the senator to be in excellent condition for a man of seventy-four. Mrs. Borah herself later said he recalled thinking how well her husband looked the morning of his brain hemorrhage.

Doctors assured Mary Borah there was no hope for the senator’s recovery and he remained in coma for most of the next several days. Occasionally Borah would come out of the coma and asked Mary for his house slippers. On Friday evening, January 19, 1940, William Borah died while his faithful secretary of many years, Cora Rubin, stood by his bedside.

To this day, no one has served longer in Congress from the State of Idaho than William Borah. The tallest mountaintop in Idaho is named for the late senator. Idaho also donated an imposing statue of William Borah to Statuary Hall in the Capitol Building.

Mary Borah lived another thirty-seven years in Washington, D. C., much admired and remembered only dimly as the widow of the once mighty Lion of Idaho.