Americans have always been fascinated with entertainers and Eddie Cantor was nothing if not an entertainer. Cantor was one of those few stars who conquered every popular entertainment medium of his time; stage, film, recording artist, television and radio. Eddie Cantor could do it all, sing, dance, act, and was a comedian. Cantor was also a songwriter and there are very few who have not heard the introduction of Warner Brothers’ “Merrie Melodies” cartoons (think Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, etc.); it was Eddie Cantor who wrote, along with two friends, Merrily We Roll Along, which was used by the studio at the beginning of every cartoon from 1937 – 1964. It was Eddie Cantor who came up with the slogan “March of Dimes” for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Cantor was, in his spare time, also a best-selling author.

Eddie Cantor literally rose from living in a ghetto, going hungry, and never having finished school to becoming one of the biggest stars in the world during his time. Cantor sang on the streets for pennies, slept on rooftops, and worked any number of jobs before finding success.

Cantor was one of the first entertainers to gain enormous popularity over the air waves and charmed his audience by referring to his family life. The comedian’s wife Ida and their five daughters were almost as well-known as Cantor himself.

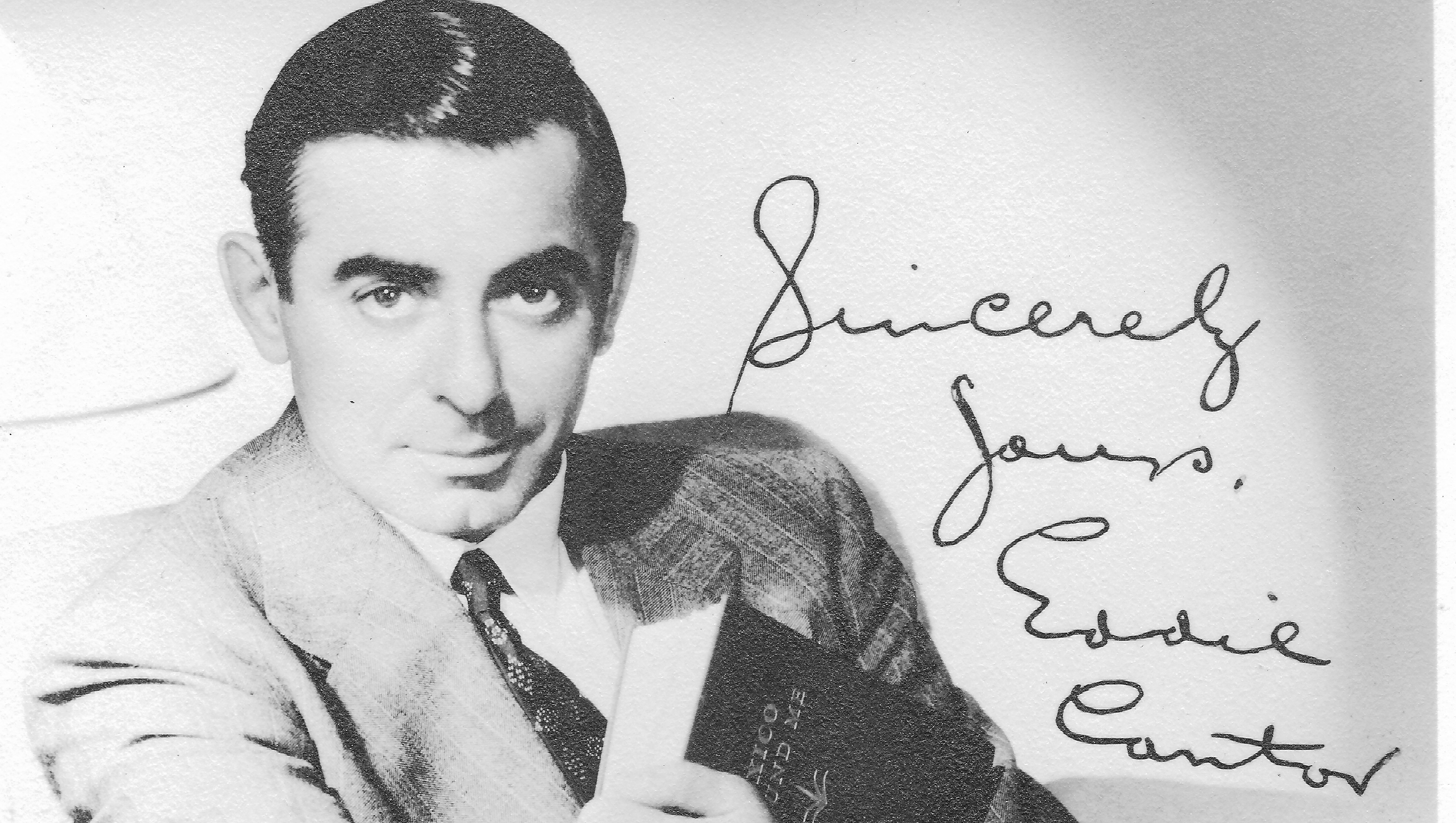

Perhaps one reason Cantor is little remembered today is because he often appeared on the Broadway stage, appearing in what was then known as “blackface” while singing. The dark makeup emphasized Cantor’s large eyes, so large in fact he was nicknamed “Banjo Eyes.”

Aside from being an entertainer, Cantor was proud of his Jewish heritage and raised many millions for the causes he believed in and was a humanitarian.

Cantor was born September 21, 1892 as Israel Iskowitz, the child of Russian immigrants. The facts about Cantor’s early life are frequently hazy, but his mother apparently died in childbirth and his father passed away two years later from pneumonia. Eddie was raised by his grandmother, Esther Kantorwtiz. “Grandma Esther” spoke little or no English and communicated with her grandson in Yiddish. Eventually Eddie’s name became confused with that of his grandmother and was shortened to “Kanter.” “Izzy” was replaced with “Eddie” when the comedian first met Ida Tobias, who felt that his name would not be appropriate for one who aspired to be an actor. The result was “Eddie Cantor.”

Eddie and Ida were married in 1914 and the marriage produced his famous five daughters, Marjorie, Natalie, Edna, Marilyn and Janet. During the peak of Cantor’s radio career, he frequently made references to his daughters and a running gag concerned his efforts to try and marry off his children. The impression was the Cantor daughters were unattractive and it was not uncommon for people to meet the girls in person and find they were quite attractive indeed. Naturally, Eddie’s daughters did not always appreciate his humor at their expense.

As a youngster, Eddie began winning notice and talent contests. Cantor was hired as a singing waiter at a saloon on Coney Island. While Cantor waited tables and sang, Jimmy Durante played the piano. Eddie moved up to vaudeville and made his Broadway debut in 1917. Cantor had been signed by perhaps the most noted impresario on Broadway, Florenz Ziegfeld. Eddie Cantor was a star of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1917 and continued to work for the producer for a decade. A shrewd negotiator, Cantor’s salary quickly escalated and he was soon making thousands per week. There were a host of familiar names in the Follies, including W. C. Fields, Bert Williams, Fanny Brice, and Will Rogers.

Eddie Cantor’s success was not limited to the Follies, as he began appearing in other Broadway musicals, although few producers could match the lavishness of Flo Ziegfeld. Cantor scored a huge hit with Whoopee! in 1928. That was the musical that introduced the song, “Making Whoopee.”

“Another bride, another groom,

Another sunny honeymoon,

Another season, another reason,

For making whoopee.”

1929 was a terrible year financially for Eddie Cantor, as it was for millions of other Americans. Cantor had invested virtually every penny he had ever made, estimated at $5 million, in the stock market and lost it all when the market crashed that October. To better understand the extent of Eddie Cantor’s financial disaster, one can consider that $5 million at that time was the equivalent to almost $70 million today.

Cantor kept his sense of humor despite being devastated by his loss, kidding with audiences.

Eddie Cantor’s popularity on Broadway caused Hollywood to beckon and he made at least two silent films. Being a singer, silent films did not offer Cantor a good vehicle and his greatest success would come over the radio before the Hollywood studios made overtures again. Evidently, Cantor did turn down a role in the first successful “talkie” movie, The Jazz Singer, which made Al Jolson a sensation.

Eddie Cantor replaced Maurice Chevalier as the host of the Chase and Sanborn Hour in 1931. Cantor was an immediate success and would remain on the radio almost until the end of his life.

Cantor introduced characters like the “Mad Russian” and “Parkyakarkus” who spawned one-liners that became national catchphrases. Eddie Cantor was usually a shrewd judge of talent and helped to discover a popular entertainer with special significance to Tennessee, Dinah Shore. Cantor also either discovered or had a hand in discovering Deanna Durbin and Eddie Fisher.

Beginning in 1934, there was a birthday ball held in the nation’s Capitol honoring the most famous victim of polio, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The ball became an annual event every January 30 and helped to raise money to fight poliomyelitis. Cantor was invited to join several movie studio executives to discuss a birthday ball for FDR in California to raise money. Cantor argued that the fundraising drive would have far more success in asking everyone to join in, rather than targeting large contributions from wealthy individuals. Cantor suggested inviting radio listeners to contribute a single dime to fight polio and came up with the phrase, “March of Dimes”. Eddie Cantor was right and joined by other entertainers, all of whom urged listeners to send their dimes to the White House. President Roosevelt was literally flooded with dimes, receiving almost 2,700,000 of ten-cent pieces.

Hollywood called again and Cantor returned to the West Coast for a movie version of Whoopee. Eddie Cantor made a series of successful film musicals for Samuel Goldwyn, perhaps the most prosperous of Hollywood’s independent studios.

After 1937 Eddie Cantor’s film career slowed down, although he remained hugely popular on radio. Cantor augmented his income through personal appearances, traveling with much of the cast of his radio show. Performing as many as five and six times daily, Cantor broke records in most of the cities where he appeared.

Cantor returned to the scene of his greatest success, Broadway with a show specially written for him, Banjo Eyes, in 1941. The show was not a success and Cantor was ill and he closed the run, returning to his Beverly Hills home.

Eddie Cantor appeared in Warner Brothers’ Thank Your Lucky Stars, a star-studded film made to boost morale during World War II. Every star on the Warner Brothers lot appeared in the film, including Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn, and Bette Davis. Every star in the movie donated his or her salary to the Hollywood Canteen, which provided a place for members of the armed services to eat, drink and dance. Jack Warner, head of Warner Brothers, also donated the profits from the movie to support the war effort.

The swashbuckling Errol Flynn, sporting a handlebar moustache, sang an English pub song, “That’s What You Jolly Well Get.”

There were some excellent performances by some of the lesser stars appearing in the picture, including Hattie McDaniel (she was “Mammy” in Gone With the Wind) who belted out a jazzy number, “Ice Cold Katie.” Jack Carson and Alan Hale (father of the actor of the same name who is remembered for playing the “Skipper” on Gilligan’s Island) did a remarkable song and dance number.

Cantor had a dual role in the film, playing himself as well as a character.

Critic James Agee said of Thank Your Lucky Stars, “It is the loudest and most vulgar of the current musicals. It is also the most fun.”

Eddie Cantor produced and starred in a movie, Show Business, with comedienne Joan Davis and future California U. S. senator George Murphy in 1944 for RKO Pictures. With his film career slowing down, Cantor concentrated on his still successful radio show and remained busy raising money for his favorite charities. Cantor made the occasional movie but by 1950, his film career was all but over. Yet there was the new medium of television and Cantor topped that as well. Eddie Cantor was one of the original hosts of the Colgate Comedy Hour, alternating hosting duties with some of the biggest names in show business at the time. Abbott and Costello, Martin and Lewis (that would be Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis for some of our younger readers), and Donald O’Connor all headlined the variety show on alternating weeks.

Cantor’s appearances were highly rated and popular. Known for decades for his energy while performing, Eddie Cantor actually suffered a heart attack during one of the live performances. Ever the consummate professional, Cantor gave little indication he was ill, much less having a heart attack. From that point on, Eddie Cantor’s energy diminished significantly and he was not the same entertainer.

Warner Brothers issued a movie based on Cantor’s life, The Eddie Cantor Story. Not surprisingly, it was a highly fictionalized version of the famed comedian’s life, featuring an unknown performer as Cantor. The film was a disaster, although Cantor recorded all the songs for the movie and his voice remained amazingly good. Even with his famed energy ebbing, Cantor pushed himself on behalf of raising money for charity. Once Cantor was promoting the sale of Israeli bonds and urged his friend Jack Benny to purchase some. Benny handed Cantor a blank check and said, “Eddie, here is a blank check. Fill it out in the amount you think I should buy and I will sign it.”

Eddie Cantor hurriedly wrote in an amount well into the five figures and true to his word, Jack Benny signed it.

With his energy flagging after repeated heart attacks, Eddie Cantor’s career began to wind down. Cantor sold the magnificent house on Roxbury Drive in Beverly Hills, moving to a smaller home with his wife. Cantor’s daughters were grown and off living their own lives, save for his eldest, Marjorie. Marjorie Cantor had devoted herself to her father and his career. When Eddie Cantor failed to worry, Marjorie worried for him. Marjorie was involved in every facet of her father’s professional life. With both of her parents suffering from heart trouble, Marjorie worried even more.

In his excellent biography of Eddie Cantor, Banjo Eyes, Herbert Goldman relates the terribly saddening failure of Marjorie Cantor’s own health. Noticing a growth on her leg, Marjorie discovered it was cancer. Despite numerous treatments, the cancer was remorseless and relentless, ravaging Marjorie’s body. Ida Cantor, accompanying her daughter to the hospital once, was aghast when she saw her daughter undressing and saw just how emaciated Marjorie had become. Marjorie finally lost her battle with cancer, dying in 1959. She was only forty-four years old.

Both Eddie and Ida Cantor were utterly devastated by Marjorie’s death and neither was ever well again. Eddie’s heart condition was so bad that he was virtually confined to his home. Ida wasn’t doing much better and finally her own heart failed in the summer of 1962. Cantor was thoroughly depressed by having lost his oldest child and wife within a short span of three years. The comedian sold the Palm Springs home that Ida had bought for him as a surprise for very little.

Housebound, Eddie Cantor lived out his remaining years in Beverly Hills, surrounded by his daughters and grandchildren. On October 10, 1964, Eddie Cantor’s ailing heart finally gave out.

Hardly perfect, old fashioned, and “corny” to some, despite his flaws, Eddie Cantor was a legendary entertainer.