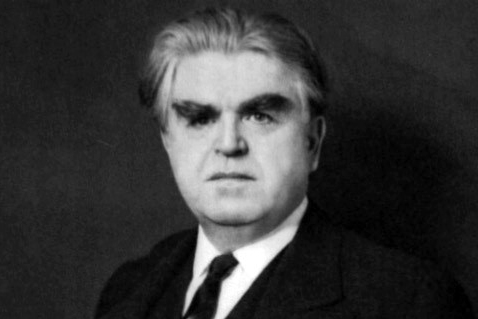

John L. Lewis

By Ray Hill

Perhaps the most famous union leader in American history today is the late Jimmy Hoffa and that is most likely due to the circumstances surrounding his disappearance. For decades, the most prominent labor leader in the United States was John Llewellyn Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 until his retirement in 1960. Lewis was a cartoonist’s dream with a memorable physical presence that lent itself to being spoofed. His massive head with an impressive mane of hair and equally remarkable eyebrows made him truly distinctive. John L. Lewis was also a brilliant speaker who sounded less like a miner than an old-time Shakespearean actor. Indeed, Lewis honed his verbal skills by reading Shakespeare and the Bible and was a master of the English language. Lewis was an omnipresent figure in the United States for decades and a colossus in the business and political lives of American society. Tangling with titans of industry or presidents of the United States made little difference to John L. Lewis.

With a forbidding appearance and a gruff manner, one president of a local union remembered John L. Lewis as “a gentle, interesting, ordinary man.” “Don’t get me wrong,” James Kelly told a reporter, “although he was friendly, John L. could be stern and when it came to business he wouldn’t stand for any foolishness, but every time I talked with him I found him to be very gentle.” Yet Kelly noted there was another side to John L. Lewis. The district president recalled, “We found he wasn’t rough – – – unless he was pushed and then he could really get rough.”

John L. Lewis once said, “The working man has as much right to gather together to improve his lot in life by talking with management as Judge Elbert Gary had in putting together Carnegie Steel and other firms to for U.S. Steel Corp.”

Lewis was as successful as he was highly effective and the membership of the United Mine Workers appreciated his leadership. Lewis was aggressive on behalf of his members and never ran away from a fight; quite to the contrary, John L. Lewis was thoroughly capable of picking a fight if he thought it was beneficial to the United Mine Workers. Lewis swept past his opponents and won high wages for his members, who performed a vital, although backbreaking and highly dangerous job. It was John L. Lewis who was largely responsible for molding the CIO into a formidable political and economic engine. Indeed, it was Lewis who formed the Congress for Industrial Organizations which rivaled the craft-oriented American Federation of Labor.

Nor was Lewis afraid of controversy, opening himself to severe criticism by calling for a strike during the Second World War. Opponents bitterly charged Lewis and his union with impeding the war effort and aiding the enemies of America. Lewis was the only major labor leader in the United States to call for a strike while the country was fighting World War II.

Much can be discerned about John L. Lewis’s personality when considering an incident in his youth. Lewis had been kicked by a mule and promptly picked up a “sprang” (the wooden brake lever of a coal car) and brained the ornery creature.

John Llewellyn Lewis was unusual in most respects and that applied to his own personal politics, as he was a Republican, yet few worked harder or contributed more to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s smashing 1936 reelection victory. Yet Lewis was something of an isolationist in his outlook on American foreign policy and he dramatically broke with Franklin Roosevelt in 1940 and endorsed GOP presidential nominee Wendell Willkie.

Another thing newsmen loved about the colorful union boss was the fact he was excellent copy for newspapers. John L. Lewis could be blunt to the point of insult, deliberately so and his quotes always made for good reading. The lash of Lewis’ tongue spared no president of the United States. Of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who quoted Shakespeare by uttering “a plague on both your houses,” Lewis once huffed, “It ill behooves anyone who has supped at labor’s table and who has been sheltered in labor’s house to curse with equal fervor and fine impartiality both labor and its adversaries when they become locked in a deadly embrace.” Lewis famously once described FDR’s vice president, John Nance Garner of Texas, as “a labor-baiting, poker-playing, whiskey-drinking evil old man.” Lewis and the equally plainspoken Harry Truman traded memorable barbs. John L. Lewis said of President Truman, “He is a man totally unfit for the position. He is careless with the truth. He is a malignant scheming sort of individual who is dangerous not only to the United Mine Workers but dangerous to the United States of America.” Harry Truman once snapped, “I wouldn’t appoint John L. Lewis dogcatcher.”

The observations of John L. Lewis about his fellow labor leaders were no less generous. He dismissed Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, by describing him as, “A pseudo-intellectual nitwit.” Lewis thought George Meany, president of the AFL-CIO, was “An honest plumber trying to abolish sin in the labor movement, which is not a function of the labor movement.”

“You need men and I have all the men and they are all in the palm of my hand,” Lewis once roared during a labor dispute. “And, now I ask, what am I bid?”

John L. Lewis was born in a tiny town in Iowa and like many, failed at running for office and business before becoming heavily involved in the burgeoning organized labor movement. His parents were immigrants from Wales. The head of the AFL, Samuel Gompers, launched John L. Lewis by hiring him as a union organizer. Lewis knew the mines and he knew the miners; he also came to know every coal and steel-producing district in the country.

Lewis became the acting president of the UMW in 1919 and called a strike that caused 400,000 miners to walk off their jobs. It was the first major coal strike in American history. The administration of President Woodrow Wilson obtained an injunction from a federal court, which Lewis and his miners recognized and obeyed. Lewis’ obedience to any court, federal or otherwise, was not a given. There were at least two notable occasions when John L. Lewis was found to be in contempt of a court order. Once Lewis and the UMW were fined $2.1 million, which was real money at the time.

The following year, John L. Lewis was elected president of the United Mine Workers and remained in that post for the next forty years without interruption.

It was not long before Lewis was recognized, not only for his ability to communicate but also for his intelligence and ability to navigate the political rapids, which is a considerable talent. Lewis constantly fought for better wages for the members of his union, as well as for improving mine safety. It might surprise some to note one person impressed by John L. Lewis’ skills and capability was President Calvin Coolidge, who offered the union leader a spot in his Cabinet as Secretary of Labor. Lewis turned it down.

Lewis could be reasonable and was criticized by some when he accepted a measure of automation in the coal mines following the Second World War, which meant the loss of some union jobs. “It is better to have half a million men working at good wages and high standards of living than to have a million men working in poverty and degradation,” Lewis explained.

John L. Lewis, during his forty years as president of the United Mine Workers, fused his organization into an effective entity, the result of which was not only better pay and higher wages, but also pensions, union hospitals, and underground travel pay. Lewis once explained his role as president of the UMW, saying, “I am their agent. They pay my salary. They keep me in good clothes. They buy me cigars. I work for them. I expect to continue.” And he did.

Once, speaking before a Senate committee in 1949, Lewis discussed mine safety, telling senators that 1,259,081 men had been killed working in the mines since 1930. Lewis then said in his booming voice, “If I had the powers of a Merlin, I would march that million and a quarter men past the Congress of the United States – – – the quick and the dead.

“I would have the ambulatory injured drag the dead after them . . . trailing their bowels. I would have the concourse flanked by five weeping members of each man’s family, six and a quarter million people, wailing and lamenting.” Needless to say, John L. Lewis could conjure a vivid image with his words.

Lewis was also human. When the CIO rejected his plea to support Wendell Willkie over President Roosevelt, John L. Lewis petulantly resigned his post. Lewis was also bold and it was said his break with Roosevelt was largely due to his own personal ambition. Fellow labor leader Phillip Murray and John L. Lewis went calling at the White House and Murray later remembered Lewis clearing his throat dramatically. “Mr. President,” Lewis announced, “I would like a place on the ticket.” Lewis was referring to the vice presidential nomination of the Democratic Party to run with Roosevelt in the 1940 election.

Without missing a beat, the president retorted, “Oh, you want a place on the ticket, John? Just what place did you have in mind?”

Without another word, according to Phillip Murray, Lewis rose from his seat and stalked out of the Oval Office and returned to his own Republican Party.

Following his retirement as president of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis was awarded the Medal of Freedom, the highest honor the American government can bestow upon a citizen who is a civilian. In an interview shortly after his eighty-fifth birthday, the former labor leader reflected upon being awarded the Medal of Freedom. The reporter wrote Lewis’ head “sunk on his chest and he seemed to take a long, thoughtful look over his half-century as one of the nation’s most controversial and powerful labor leaders, then he broke into a wry smile.”

“So they gave me a medal for doing all those things they fought me for doing all those years,” Lewis said.

For one who had basked in the limelight for decades, John L. Lewis was also highly cognizant that he had also been roasted and blistered in the newspapers during that time as well. A powerful presence and impossible to ignore, Lewis accommodated himself to the sidelines and the shadows. It was largely through the influence of John L. Lewis that W. A. “Tony” Boyle became president of the United Mine Workers following the death of Lewis’ handpicked successor. One of Lewis’ aides explained the boss’s attitude, telling reporter Neil Gilbride, “He knows his heyday is past and he sees little value in getting into newspaper scraps with other labor leaders.”

The former union president was not tempted by the sumptuous financial offers by publishing companies and magazines who begged for his memoirs. Even after his retirement, Lewis maintained an office at the United Mine Workers’ headquarters. Lewis could hold court in a “club-like lounge on the 6th floor” of the UMW building.

Lewis continued living in his relatively modest home in northern Virginia and continued going to his office almost to the day he died. John L. Lewis was rushed to the hospital on June 11, 1969, suffering from internal bleeding. The old warrior went to sleep and drifted away. Admittedly a terror to some, John L. Lewis was a hero to others and a legend, especially inside the organized labor movement. By any measure or standard, John Llewellyn Lewis stands alone as an American original. While he became famous and was oftentimes vilified, it is indisputable as the “agent” of his miners he helped to lift them up and improve their lot and lives.