Tennessee has produced some remarkable leaders during the history of our country, as well as some rascals. Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson all served as presidents of our country; Howard Baker and Bill Frist served as Majority Leaders of the United States Senate. Kenneth McKellar was acknowledged to be the single most influential member of the United States Senate during much of the decade of the 1940s. Cordell Hull is the longest-serving Secretary of State in our history.

Only three Tennesseans have wielded the Speaker’s gavel in the House of Representatives. The first Tennessean ever to serve as Speaker of the House in Congress was John Bell, one of the most distinguished sons of the Volunteer State who held numerous public offices within the gift of the people. Bell served as Speaker from 1983 – 1835 and was followed into office by another Tennessean, albeit of a different political party, James K. Polk, who served from 1835 – 1839. The last Tennessean who occupied the Speaker’s chair in the United States House of Representatives was Joseph Wellington Byrns of Nashville.

Tennesseans fared better as the leaders of their political party in the House; Congressman James Daniel Richardson of Murfreesboro was among the earliest Minority Leaders of the U. S. House of Representatives, serving from 1899 – 1903. Finis Garrett, an eloquent West Tennessee congressman was the Minority Leader from 1923 – 1929. Garrett voluntarily left the House to challenge Senator K. D. McKellar for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate in 1928 unsuccessfully. Had Garrett chosen to remain in the House, he very likely would have been Speaker in 1931. A profoundly conservative Democrat, it is interesting to contemplate how things might have been different during Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal had Finis Garrett sat in the Speaker’s chair.

Joseph W. Byrns had represented Nashville or Tennessee’s “Hermitage District” in Congress since his election in 1904. Byrns proved to be enduringly popular inside his district and he was routinely reelected, which gave him ever-growing seniority. In his own district, Byrns was known as a “non-vacation man”, meaning he worked steadily at his job with few or no hobbies to otherwise occupy his time. Dean of the Tennessee Congressional delegation, Byrns was well known for keeping his office open and when he was away from Washington, D. C., it was usually to speak inside the district of a fellow congressman or a Democratic candidate. Byrns maintained the same schedule when at his home office, seeing anyone who wished to see him and moving around the district constantly during the evenings. Jo Byrns was known for his friendliness as a person and welcomed all his callers with a pleasing informality that made his guests feel comfortable.

Just before he assumed office as the Speaker of the House, Jo Byrns was interviewed by Orland K. Armstrong for the Chattanooga Daily Times. Armstrong marveled Byrns had been reelected, largely without opposition, ever since he went to Congress in 1908. “How do you do it, Mr. Byrns?” Armstrong wondered.

Orland K. Armstrong wrote Byrns looked at him “quizzically” from beneath his “shaggy eyebrows”, shifted “one leg over the other” and ran a hand “over his thinning gray hair” and grinned “a wide, pleasant grin.” “Well, suh, I reckon I’m here because I’ve always tried to tend to business,” Byrns replied. “Never gone galavantin’ round the country on junkets. No, suh! I stay here when congress is in session, and when it ain’t, I get acquainted with the folks again, suh!” A simple, yet effective means for a congressman to represent his own district.

Jo Byrns also had a reputation for having a remarkable memory and the ability to remember names and faces, a God-send to most politicians.

When he first went to Congress, Jo Byrns met with the Speaker at the time, “Uncle Joe” Cannon, a Republican from Illinois. Byrns provided Speaker Cannon with a list of the important House committees he wished to serve upon. The assignment he got from the cantankerous Cannon was the Indian Affairs Committee. “I reckon Speaker Cannon figured since there wasn’t an Indian in the whole state of Tennessee, I could approach the problem with an unbiased attitude,” Byrns said wryly years later.

It was Speaker Champ Clark of Missouri, a Democrat, who gave the lanky Tennessean the committee assignment he hoped for: a seat on the House Appropriations Committee. As chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, Byrns was constantly accosted by those wanting money. There were always unceasing cries of “We need this!” “We must have that!” Orland K. Armstrong wrote in his profile of Byrns. Congressman Byrns always said, “Yes, suh! I’ll see about it!” And see about it he did.

The shaggy eyebrows that so delighted cartoonists came about because of a “joke” played upon Byrns when he was quite young. Evidently, Jo Byrns fell asleep in a barber’s chair and the barber proceeded to shave off his eyebrows. That incident, according to Joe, Jr. “marked him for life.”

When a fusionist movement was attempting a revival in Tennessee, Congressman Jo Byrns in introducing Postmaster General James A. Farley to an audience, cried, “General, you are hearing talk about a fusion movement in Tennessee against the regular Democratic nominees. Don’t let it disturb you. We’ll take these fusionists for a killing in the November election and bury them with their faces down.”

Byrns rose steadily through the ranks of his party, first as chair of the powerful House Appropriations Committee and then Majority Leader under Speaker Henry Rainey of Illinois. When Rainey died suddenly in August of 1934, Jo Byrns was elevated to the Speaker’s chair.

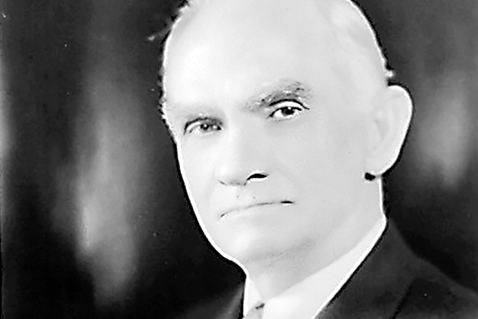

Tall (quite nearly 6’2), lanky with thinning white hair and a magnificently bushy set of black eyebrows, Jo Byrns was well regarded by his colleagues. After all, people skills are quite necessary for folks to rise to leadership positions inside any legislative body whether it be a County Commission, City Council or Congress. Like most congressmen, Joseph W. Byrns had hankered for a seat in the United States Senate. McKellar appeared to be too formidable to challenge, but a seat came open with the death of Lawrence D. Tyson. Cordell Hull almost instantly announced he would be a candidate in the Democratic primary and Byrns, although highly cautious, finally took the plunge. Byrns would have certainly had the backing of his own Davidson County and was encouraged to run by Edward Hull Crump, the leader of the Shelby County political organization. It would have been a nip and tuck race and Byrns had a fair chance of winning. Byrns gave the opening speech of his senatorial campaign and suffered a mild heart attack while making his talk. After a few days of rest, Byrns withdrew from the senatorial campaign and announced he would seek reelection to his seat in the House instead. That placed Jo Byrns on the trajectory to finally become Speaker of the House.

Byrns was sixty-four years old when he climbed atop the Speaker’s dais and took the gavel in hand. Politically secure inside his congressional district, like most every other Democrat in Tennessee, Congressman Byrns was an ardent supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and virtually all of the New Deal. Every Speaker has his/her own style of trying to keep the members of his/her political party together and Byrns was not the sort to browbeat or threaten his brethren. Rather, Jo Byrns asked for help and usually got it. There were some who believed Byrns ought to have employed a more dictatorial style in his approach, but it simply wasn’t the Speaker’s nature. A kindly, thoughtful man, Jo Byrns accomplished his goals through attention to detail and hard work. Byrns had built up a following amongst his fellow Democrats through his chairmanship of the Democratic Campaign Committee for the House of Representatives. Through that committee, Byrns aided countless colleagues and aspiring congressmen in their campaigns and doled out contributions.

Tennesseans were enthused and elated at the notion one of their own would sit in the Speaker’s chair. While lamenting the passing of Speaker Henry T. Rainey, the Chattanooga Dailey Times published an editorial entitled “Byrns for Speaker.” Byrns had declared his candidacy following the passing of Henry Rainey. “My friends understand that I am going to make the race, because they feel and I feel that I am in line for it,” Byrns said. “There is not a shadow of doubt about my election.”

Yet there were others who coveted the exalted position on the Speaker’s dais, all of whom were congressmen from the Southland. Sam Rayburn of Texas – – – who was born in Tennessee – – – was anxious to serve as Speaker, as was William B. Bankhead of Alabama. The last prospective candidate was John E. Rankin of Mississippi, an unabashed racist who made a name for himself as an advocate for veterans. Rayburn, who would eventually become the longest-serving Speaker of the House of Representatives, was disadvantaged by the fact Vice President John Nance Garner, the presiding officer of the United States Senate, was also from Texas.

Byrns had sought to fill the Speaker’s chair when Garner, the previous Speaker, had been elevated to the vice presidency in 1933. It had been a three-way contest between Rainey, Byrns and John McDuffie of Alabama. It was considered a “Battle of the Giants” of the House of Representatives. Byrns had surprised quite nearly everybody when he suddenly withdrew as a candidate for Speaker and threw his support to Henry Rainey. Much of Byrns’s strategy had been the brainchild of Congressman Edward Hull Crump of Memphis. The leader of the Shelby County machine served four years in Congress from 1931 – 1935.

The formal announcement Joseph W. Byrns would run for Speaker of the House to replace the late Henry T. Rainey came on August 24, 1934. That announcement was made by Congressman Sam D. McReynolds of Chattanooga, a very close friend of Byrns. McReynolds had been the campaign manager for Byrns in the Nashville congressman’s first bid to become Speaker of the House. McReynolds, like every campaign manager, proclaimed Byrns would be elected “by an overwhelming majority.”

“In a long-distance telephone conversation this morning with Representative Joseph W. Byrns at his home in Nashville,” Sam McReynolds told reporters, “he authorized me, as chairman of the Tennessee delegation, to say that he is a candidate for Speaker of the House in the 74th Congress, succeeding the late Speaker Henry T. Rainey.” McReynolds added Byrns was expected to return to the Capitol in a few days and might “have some further statement to make.” From Nashville, Byrns said he had done “absolutely nothing” in the way of campaigning to become Speaker, yet he insisted he was “exceedingly confident” of his election.

While campaigning in Gallatin, Tennessee, Senator K.D. McKellar said to his audience, “I’ll tell you confidentially that he [Byrns] will be the next speaker of the house.”

With the fall elections behind them and as Democrats prepared to return to Washington, D.C. and elect a Speaker, it was all but certain Joseph W. Byrns would achieve his cherished ambition to wield the Speaker’s gavel. When asked what he expected to accomplish as Speaker, Byrns thought for a moment, before saying, “I’ll try to keep the boys workin’ as hard as possible.”

On January 2, 1935, House Democrats met in caucus and selected Joseph W. Byrns of Nashville as their nominee for Speaker of the House. Students at the Stratton School in his district had fashioned a special gavel for the incoming Speaker, made of wood from Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage estate. On January 3, Byrns was formally elected as Speaker of the House, defeating GOP nominee Bertram Snell of New York.

Jo Byrns only served as Speaker for 17 months before dying suddenly on June 4, 1936. President Roosevelt praised the late Speaker as, “Fearless, incorruptible, unselfish, with a high sense of justice, wise in victory” and as one who “served his state and the nation with fidelity, honor and great usefulness.” Byrns is the last Tennessean to serve as Speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives.