The Gentleman From Colorado

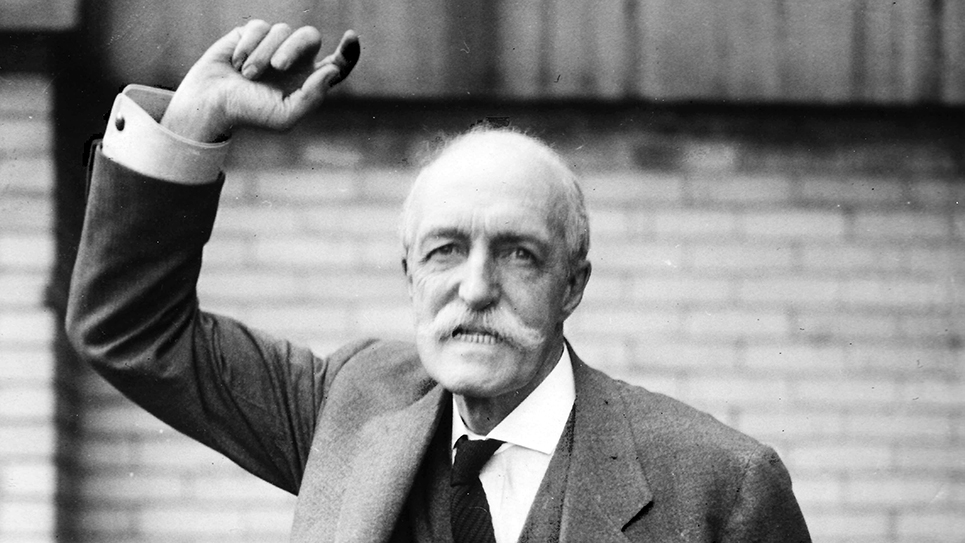

Eugene D. Millikin

For sixteen years, Eugene Donald Millikin represented Colorado in the United States Senate. An attorney by profession, Millikin had one of the best tax minds in Congress and was considered an expert in the field of taxation. A man of wit and ability, Gene Millikin was highly popular with his colleagues. Millikin was one of the best operators inside the Republican cloakroom of the Senate. A journalist who covered Millikin once described him as “the heavy-duty Senator with the light touch.” That same writer thought Gene Millikin was “a man of inner gaiety and earthly humor which not even taxes nor tariffs can blunt.” Millikin was fond of saying, “I am always pleased to cooperate with the inevitable.”

As he prepared to leave the Senate in 1956, Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson hailed Gene Millikin as one “who never talks too much or thinks too little.” Vice President Richard Nixon, speaking about the retirements of Millikin and Georgia Senator Walter F. George, said, “So great is the stature of these two men that few have dared to tangle with them and those who did invariably came out second best. They were, they are champions.”

On December 1, 1941, Senator Alva Adams, the son of a governor and nephew of another, died of a heart attack. Twenty days later, Governor Ralph Carr announced he had appointed Eugene D. Millikin to fill the vacancy. Carr told reporters Millikin was a “Republican of today, a man who will be respected by his colleagues in Washington and who will reflect credit upon his state.” “And that is why I appointed him,” the governor explained. Carr then surprised many of those present when he said, “Mr. Millikin does not yet know that he had been selected.”

Eugene Millikin confirmed that when reporters found him working at his law office. The newly appointed senator said he was surprised. “I did not know I had been decided upon,” Millikin told newsmen. Caught unawares, Millikin acknowledged he was not sure of his immediate plans, but said he “would go to Washington tonight, if needed.”

Eugene Millikin’s path to the Senate began when he was the chief of staff to Governor George Alfred Carlson, who served from 1915-1917. Millikin practiced law, and his law partner was U.S. Senator Karl Schuyler. During the brief time Schuyler was in the Senate, Millikin served as an aide. After the death of Senator Schuyler, Millikin was the lawyer for the senator’s estate. It was during that time that Millikin fell in love with Schuyler’s widow, Delia, and married her. They were together for the rest of Gene Millikin’s life.

Almost immediately, Senator Millikin had to prepare to run for the remaining two years of the term. Both of Colorado’s seats in the United States Senate were up for election in 1942 as a result. Governor Carr ran for the regular six-year term against incumbent Edwin C. Johnson, a Democrat. It was a good year for Republican candidates and Eugene Millikin handily beat his Democratic opponent while Governor Carr lost narrowly to “Big Ed” Johnson.

Two years later, Senator Millikin was reelected to a full six-year term.

As Governor Ralph Carr had anticipated, Eugene D. Millikin did indeed become one of the most able and respected members of the United States Senate. Millikin was also one of the more able debaters of the Senate. TIME magazine recorded a floor debate between Millikin and Paul Douglas, a former professor of economics from Illinois. Douglas had been painting a verbal picture of a harried housewife, worried about the economy as she worked over a hot stove. Senator Douglas noted the Republican administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower had recently published a helpful brochure on ways to prepare rabbit. Gene Millikin retorted that the previous Democratic administration had once produced a screed on “the love life of a watermelon.” Douglas charged the Republicans with sponsoring tax bills that he claimed benefited only the rich. Millikin shot back, “Dear Senator, if that did not come out of your mouth, I would call it sheer claptrap– and it is still claptrap, even though it comes out of your mouth.”

Senator Millikin chaired the Senate Finance Committee when the Republicans controlled the Senate in 1947-1949 and again from 1953-1955. Although from different political parties, Gene Millikin and “Big Ed” Johnson proved to be a formidable team, and the two worked together in harness for the people of Colorado. Both Millikin and Johnson won ample praise from many of Colorado’s newspapers for working together on a bipartisan basis for the folks back home.

Eugene Millikin’s most difficult political contest occurred in 1950 when he faced two-term Congressman John A. Carroll. Even those sympathetic to Millikin worried the senator was falling behind the hard-campaigning congressman. Carroll thundered in one address that Senator Millikin had “painted such a dark picture of the 50-cent dollar that his audience came out shaking their heads in despair as they climbed into their Cadillacs.”

The 1950 campaign had gotten off to a wobbly and uncertain start after Millikin’s close friend and patron, former Governor Ralph Carr, suddenly announced he was running to reclaim the chief executive’s office. Carr had spurned efforts to run again for public office since his 1942 loss for the U.S. Senate and had said he wasn’t interested in running. Senator Millikin urged him to run, as he believed Carr would strengthen the entire GOP ticket in Colorado. Carr did announce his candidacy and was again the Republican nominee without having to actively campaign. The former governor went to the hospital, plagued by a persistent foot infection, which was complicated by diabetes. Senator Millikin moved quickly to forestall any talk of replacing Ralph Carr as the GOP gubernatorial nominee, and Carr released a hopeful letter. Colorado Republicans were stunned when Ralph Carr died suddenly on September 23, 1950.

Carr had called Millikin “Mike,” and the senator simply said he was “crushed” by the death of his friend. In the end, Millikin won by just under 30,000 votes. Senator Millikin faced Congressman John A. Carroll from Denver, who was especially popular with core Democratic groups. Carroll’s campaign was undermined that year by the most popular Democrat in Colorado, Senator Edwin C. Johnson. It was the closest race of Eugene Millikin’s career, although he won just over 53% of the vote.

Millikin’s influence inside the Senate came from his post as chairman of the Republican Conference, which was the committee comprised of all the GOP senators; that post made Millikin a member of the Republican Policy Committee. Millikin’s spot as the most senior Republican on the Senate Finance Committee gave him additional influence, although all of it was driven by his remarkable personality and formidable intellect. In many respects, Gene Millikin was Colorado’s “Mr. Conservative” who truly believed that what was good for business was good for America. One veteran news correspondent noted Millikin was always to be found “in protecting the civil rights of the unpopular,” but cautioned it was not to be mistaken for liberalism. Douglas Cater, the chief Washington correspondent for The Reporter, thought Millikin second only to Bob Taft amongst Senate Republicans and believed the Coloradan was more conservative than the senator from Ohio. Millikin did have a different outlook on American foreign policy than his friend Taft, being more internationalist in his viewpoint. Senator Millikin voted for the North Atlantic Treaty and the initial Military Assistance Program, neither of which Taft had supported. “Unlike many Senators, he clings to the old-fashioned notion that the basic purpose of senatorial debate is enlightenment,” Cater said. Having been an excellent attorney, Gene Millikin was one of the best in interrogating witnesses before Senate committees. Millikin’s speeches on the floor of the Senate were also widely admired for their humor and lucidity. Gene Millikin had loyally supported Bob Taft’s bids for the GOP presidential nomination in both 1948 and 1952.

Eugene Millikin suffered from crippling arthritis, and it began to affect him more as he served his third term in the Senate. As 1956 approached, almost everyone believed the senator would be a candidate for reelection. Reports of the senator’s health were regularly printed in Colorado newspapers, and Governor Ed Johnson was appalled to find on his desk one morning a telegram from the chairman of the Pueblo Democratic Executive Board urging the appointment of John Carroll should Senator Millikin resign. Johnson fired back a telegram stating, “I resent speculation as to what I may or may not do about vacancies which do not exist and which I hope most earnestly may not occur.” The governor revealed the exchange of correspondence at a news conference. When asked if he had anything to add, “Big Ed” snapped, “Not a word.”

The United States Senate is a very difficult place to leave voluntarily for many, and Eugene Millikin was no different. Confined to a wheelchair for several months, the senator said he was “available” to run for a third full six-year term should Colorado Republicans want him. The leading candidate to replace Millikin as the GOP senatorial nominee, former Governor Dan Thornton, had already pledged not to run against the senator. The Rocky Mountain News published an editorial begging the senator not to run again. “It would be suicide for Sen. Millikin to try and take on the rough-and-tumble political campaign that this one has already become,” the editorial insisted. The newspaper warned Colorado’s Republican Party was “facing a critical dilemma” because of the senator’s “insistence that he will run again despite his crippling physical condition that makes active campaigning impossible” for Millikin.

Senator Millikin, after a stay in the hospital, had stated he believed he would be “in shape” to run once again, but was also careful to say, “if I’m not in shape to be a candidate, I’ll not be a candidate.” Friends of Millikin said the senator was trying to pass a $156 million project for Colorado, and not until that matter had been settled would he make a final determination about a reelection campaign.

Millikin spent thirteen weeks either in the hospital or confined much of the time to his Washington apartment. Yet Millikin insisted on going to Capitol Hill in his wheelchair to help push the Upper Colorado River Project. Perhaps the saddest aspect of Millikin’s debilitating illness was that while his body failed him, his mind remained nimble and his political acumen undiminished. Over a period of a couple of weeks, friends began thinking Millikin would not run again after all.

Wan and having lost weight, his eyes hugely magnified behind large glasses, Senator Millikin announced that his health precluded his running for another term. “The final decision results from appraisal of my health situation,” Senator Millikin told a news conference. As to his plans, the senator growled there was “no chance” he would resign his seat in the Senate. Millikin was quite emphatic that he intended to serve out the remainder of his term. Two members of Colorado’s congressional delegation, William S. Hill and Edgar Chenoweth, as well as Frank Hoag Jr., publisher of the Pueblo Star-Journal, stood by as Senator Millikin made his announcement.

After leaving the Senate in January of 1957, Millikin and his wife, Delia, flew to Tucson, Arizona, where the former senator hoped the warm climate would help him. When in Colorado, Millikin and his wife lived in the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs. Mrs. Millikin told one reporter inquiring about the former senator that her husband “is better than he was when he retired, but he is still very miserable.” She added that the cold and wet spring weather had aggravated Millikin’s arthritis.

In April 1958, the Millikins returned to Denver, where they rented an apartment near the State Capitol. The former senator was carried to Denver in an ambulance to make him more comfortable. Mrs. Millikin told reporters her husband was “very tired.” In July, Eugene Millikin contracted pneumonia, which proved to be fatal. © 2025 Ray Hill