By Ray Hill

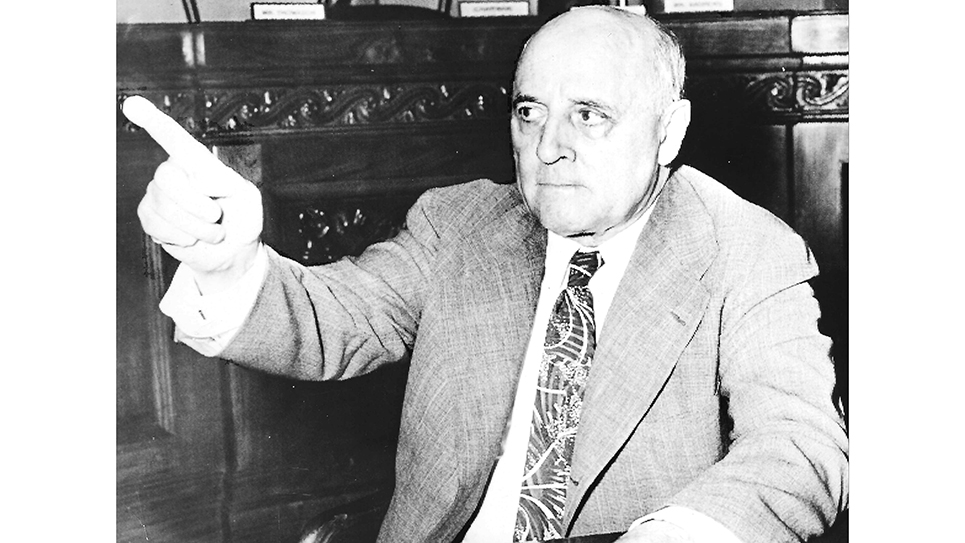

Andrew Jackson May was a colorful Democrat whose career was derailed by corruption. The backwoods lawyer from rural Kentucky was one of the fiercest critics of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the House of Representatives. May was a man who relished holding power and did not hesitate to use it. During his time in Congress, Andrew J. May rose to become chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee, a position that gave him great power, especially after the United States entered the Second World War. Yet that committee chairmanship would also help to bring him to ruin.

The most widely read news magazine in the world, TIME, noted that Congressman May “reveled in having generals at his beck & call.” Should “a ‘warm friend’ or a good constituent” want “a favor (perhaps a war contract, perhaps a son sent to O.C.S. [Officer Candidate School]), Andy would pick up a phone, summon the official to his office, and arrange it on the spot.”

Solidly built and balding, A. J. May was elected the Commonwealth’s state attorney several times, sat as a judge of the circuit court and had business interests in coal and banking. May ran against Congresswoman Katherine Langley, a flamboyant woman who had taken the place of her husband in the House of Representatives after he had been forced to resign. Mrs. Langley was popular in her own right, and when May contested the 1928 election, he lost to the Republican incumbent. Two years later, May ran again and with Kentucky, like the rest of the country, suffering from the Great Depression, he won a narrow victory in the general election.

Another challenge awaited the freshman congressman when he was forced to run statewide as Kentucky’s legislature had failed to redistrict, meaning every candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives had to run at large. Andrew J. May made an impressive showing in the 1932 election, running second out of nine inside the Democratic primary and fourth in the general election.

May’s district contained several Republicans, and while he continued to be reelected every two years, he did not win general elections with the usual majorities associated with longtime or powerful incumbents. In 1942, Republicans did well in the midterm elections, and Andrew J. May won his reelection campaign by only 540 votes over Republican Elmer Gabbard. In a rematch two years later, with Franklin D. Roosevelt at the top of the Democratic ticket, May increased his margin by more than 3,000 votes.

During his first term, Andrew J. May arrived in a House barely controlled by the GOP. The House majority was close enough that it switched due to a number of deaths, including that of House Speaker Nicholas Longworth. Following the 1932 election and the beginning of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, Andrew May became a solid supporter of the New Deal.

Congressman May represented a district that produced coal, and this was the basis of his opposition to the TVA. May reasoned that with more electric power, there would be less need for coal. TVA adherents in the House had to overcome the adamant opposition of several congressmen like Andrew May and Andrew Edmiston of West Virginia, who put coal before anything else. A coalition of opposition composed of Republicans and conservative and coal state Democrats proved to be a formidable obstacle for the supporters of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the House of Representatives. It oftentimes fell to Tennessee’s powerful Senator Kenneth McKellar to rescue TVA from its opposition in the House.

While many believed May did a good job as chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee, he was not immune to making blunders, some of them quite serious. Congressman Andrew J. May horrified most of official Washington when he returned to the Capitol following a visit to the war zone. The garrulous congressman let it slip that American submarines usually survived attempts by the Japanese Navy to destroy them because their depth charges exploded well before coming close to the submarines. Unfortunately, May made his statement at a press conference as chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee. Once his comments were public, it soon became readily apparent the Japanese read American newspapers as well and had adjusted their depth charges to explode at a far deeper depth. The commander of the U.S. Navy’s submarine fleet in the Pacific theater of the war, Admiral Charles Lockwood, thought May’s loose lips had been responsible for the loss of perhaps ten submarines and the deaths of as many as 800 seamen. “I hear Congressman May said the Jap depth charges are not set deep enough,” the admiral growled. “He would be pleased to know that the Japs set them deeper now.”

An obscure, hardworking, unassuming United States senator from Missouri came to national attention through his chairmanship of the Senate War Investigating Committee, which rummaged through paperwork, witnesses, and a myriad of details to uncover corruption and waste in contracts related to America’s war effort. The notoriety gained by Harry Truman as head of the committee, which became known as the “Truman Committee,” helped to catapult him into the vice presidency and ultimately into the White House. It was through the former Truman Committee, then headed by Senator James M. Mead of New York, that something odd came to light as it sifted through the Garsson munitions company’s records. TIME reported there was “talk of packets of $1,000 and $3,000 sent” to the congressman from the Garsson Washington office. “There was the peculiar circumstance that May had endorsed a check as the president of the Cumberland Lumber Co., which the Garssons paid for lumber that was never delivered or even cut,” the news magazine noted.

Congressman May bleated it was all a political smear. Yet the pressure brought about a sudden heart attack. May hurried back to his home in Prestonburg, Kentucky, and tried to get himself reelected.

May remained holed up at his home in Prestonburg, and May’s doctor announced the congressman was too ill with heart problems to be able to go and vote. Dr. John Archer described May as being in “critical condition,” although the congressman remained at home rather than a hospital. Dr. Archer opined that May might never be able to return to Washington, even if he were reelected.

Senator Mead told newsmen, “We are willing to wait patiently until Mr. May is well enough to testify, but we want to hear his story when he is ready to tell it.”

After his lengthy service in the House of Representatives, it soon became clear Andrew J. May had lost the confidence of many of his constituents. The congressman was opposed by the United Mine Workers’ union.

After sixteen years in Congress, Andrew Jackson May lost to an unknown Republican, 34-year-old returning veteran, Howes Meade. Meade’s victory had been overwhelming, as the newcomer garnered quite nearly 60% of the votes cast and carried all but two counties inside Kentucky’s Seventh Congressional District. Congressman May carried only two counties and only barely carried his own county of Floyd.

Enough voters believed the charges against May to have voted him out of office. Worse was to come for the former congressman when a grand jury indicted his good friends Henry and Murray Garsson, as well as the Garsson company’s business agent in the Capitol, Joseph F. Freeman. They were indicted for having conspired to defraud the government of the United States. Former Congressman Andrew Jackson May was accused of having taken $16,000 in checks and cash from the Garsson brothers, as well as arranging for the payment of $53,634 more. It was the equivalent of almost $1.2 million today, a sum which astonished many of the folks in May’s former congressional district.

May traveled back to Washington, D.C., where he pleaded not guilty and issued a perfunctory statement saying he was sure to be vindicated. The former congressman was required to sign a $2,000 bail and meekly asked, “My heart is hurting me– can I sign something and go to my hotel?”

On July 3, 1947, Andrew J. May was convicted by a jury of having accepted bribes as chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs. Murray and Henry Garsson had been charged with excessive profits from contracts steered to their company by Congressman May, and there were accusations that the company had manufactured defective mortar shells, which led to the deaths of American soldiers.

Among those who attested to May having sought favors for the Garssons was General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of War Robert Patterson.

“I was superintendent of a Sunday school and taught Bible class in Kentucky. I have never tasted liquor, wine or beer, and I have never used tobacco in my whole life,” May pleaded. “I have never received a dollar that was not honestly earned.”

Andrew May contended he and the Garssons had gone into the lumber business together to supply much-needed box lumber to the Garssons’ munitions business. May insisted he had only been the manager of the Cumberland Lumber Company. The government retorted that the Cumberland Lumber Company had never shipped “a single stick of timber to the Garssons.” May insisted he had paid it all back, “every cent of it,” or had spent it on the plant of the Cumberland company.

May, seemingly unable to accept the jury’s verdict, appealed his case to the United States Supreme Court. When the high court refused to hear his case, Andrew J. May went to prison at age 74, sentenced to serve eight months to two years. May was incarcerated at the federal prison near Ashland, Kentucky, roughly 60 miles from May’s home in Prestonsburg. Judge Henry A. Schweinhaut had refused to consider giving the former congressman a more lenient sentence, snapping, “The integrity of the national Congress is at stake.”

The former congressman served only nine months before being released. George G. Killinger, chairman of the Federal Parole Board, acknowledged the former congressman had been granted a parole. Killinger said May had an “outstanding record” while in prison and that the former congressman had been “a wonderful influence on fellow inmates.” While in prison, Andrew J. May worked at the prison library.

Ironically, it was the same man who originally headed the committee that helped to ferret out the information of May having accepted bribes that gave him a pardon. President Harry S. Truman pardoned the former congressman in 1952. That same year the Kentucky Court of Appeals restored Andrew J. May’s license to practice law, which he had lost upon his conviction.

Not everyone was forgiving. The Paducah Sun-Democrat published an editorial questioning the accolades bestowed upon Andrew J. May and took issue with House Majority Leader John McCormack of Massachusetts, who had said the people of May’s former congressional district remained proud of him. The Sun-Democrat reminded its readers that the voters of Kentucky’s Seventh Congressional District had “rejected him by an overwhelming vote when May ran for reelection while under indictment on the bribery charge.”

The editorial stated it had no wish to “belabor a criminal whose case has already been adjudged by a jury of his fellow citizens,” but protested the attempts “to honor a man who patently dishonored himself and his high responsibilities” which made the editor “a bit sick at the stomach.”

For the rest of his life, Andrew J. May loudly proclaimed his innocence. The former congressman lamented he had lost his life’s savings in defending himself and that he had been prosecuted for the sake of political expediency.

The 84-year-old former congressman was admitted to a hospital suffering from a kidney infection and “other complications.” May’s condition continued to deteriorate. Andrew J. May died September 6, 1959.

The former congressman retained some of his personal popularity in a few counties of his old congressional district. When he died in 1959, Governor Lawrence Wetherby and Bert Combs, the Democratic nominee for governor that year, attended May’s funeral rites in Prestonburg.

© 2026 Ray Hill