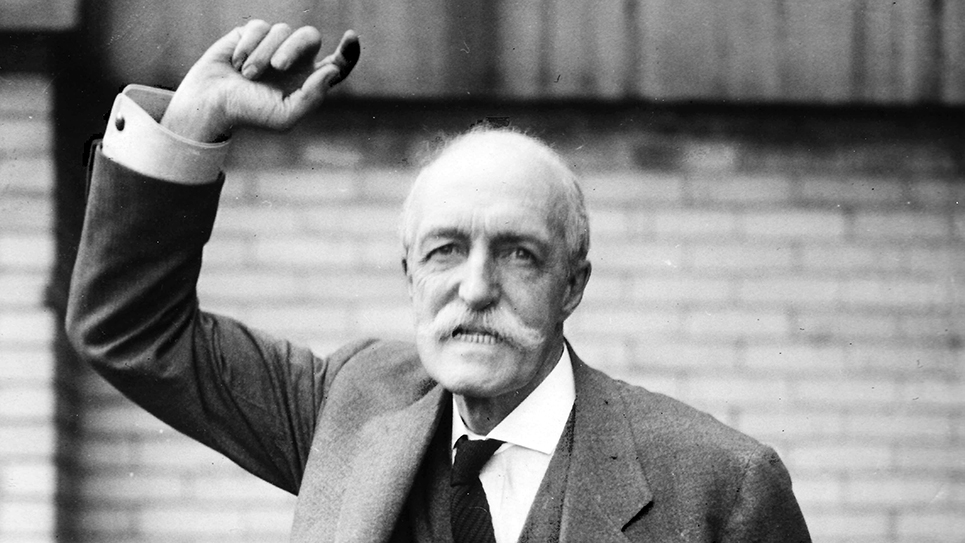

Gifford Pinchot (pronounced Pin-Show) was the epitome of the aristocrat in politics. Immensely wealthy, Pinchot dedicated himself to conservation and was a perennial office seeker. The future governor was motivated to participate in politics for a number of reasons, which included his admiration of Theodore Roosevelt and his fervent belief in the conservation of America’s forests. Pinchot was a resident of Pennsylvania, one of the most boss-ridden states in the country. The master of the Pennsylvania political machine was wealthy, corpulent Boies Penrose, who sat in the United States Senate. A powerful political machine operated in Philadelphia under Congressman William Vare. The Vare machine was unusual in that, unlike virtually every other urban big-city machine in the country, it was Republican rather than Democratic. The machine was so powerful it nominated James Montgomery Beck for a seat in Congress to represent a working-class district. Beck did not live in the district or even the state; Beck was a resident of Washington, D.C. Beck rented what TIME magazine referred to as “a sleazy apartment in a poor district of Philadelphia which he never occupied.” Beck’s residency was challenged, but he was seated after having won the election.

Gifford Pinchot was married to Cornelia Bryce, a red-headed, formidable and accomplished woman in her own right. Called “Leila” by her friends and family, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot was an ardent advocate for the rights of women and like her husband, was an outspoken progressive. She and Gifford lived at Gray Towers, the ancestral home of the Pinchot family. Like most everything else she encountered, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot left her mark on Gray Towers as well.

Gray Towers was designed and built by famed architect Richard Morris Hunt, who was responsible for Biltmore House and quite a few of the remarkable “cottages” on Millionaires’ Row in Newport, Rhode Island. Gray Towers was built in the style of a French chateau, originally situated on 303 acres with numerous other outbuildings built on the property. Gray Tower sat atop a gentle slope in Milford, Pennsylvania, overlooking the Delaware River. After Cornelia Bryce Pinchot’s death, her son donated Gray Towers to the government of the United States.

Both of Gifford’s parents came from successful families and his mother, Mary, was the daughter of Amos Eno, one of the richest developers in New York City. Pinchot’s interest in forestry was encouraged by his parents, and apparently, his father suggested he become a forester. It was while managing the forests surrounding Biltmore House that Pinchot fell in love. The object of his affection was Laura Houghteling, whose family lived nearby. The two were engaged to be married, but Laura tragically died of tuberculosis before they could be married. Pinchot’s grief was deep and profound. At the time, when someone lost a loved one, he or she wore dark clothes as a sign of being in mourning. Pinchot wore mourning clothes for several years after Laura’s death and did not marry for 20 years.

Gifford Pinchot and Cornelia Bryce became acquainted through their mutual work on behalf of progressive causes, and the two were married in 1914. Their union produced one child, Gifford Bryce Pinchot. Cornelia Pinchot was as interested in politics as was her husband. At least three times she ran for the GOP nomination for the House of Representatives, losing each time. Mrs. Pinchot was an independent and very outspoken woman for her time.

By 1898, Pinchot was head of the Division of Forestry inside the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Gifford Pinchot took what was then the somewhat unusual position that the federal government should protect and conserve the country’s natural resources, a policy that was opposed to those who had previously occupied his position. Pinchot’s view of forestry and conservation met a kindred soul in Theodore Roosevelt, who assumed the presidency following the assassination of William McKinley in 1901. The two became friends, and together they lobbied Congress to create the United States Forest Service. That federal agency was charged with overseeing the forest reserves of the country, and President Roosevelt named Pinchot as the first Chief Forester of the United States.

Pinchot continued as America’s chief forester under the administration of William Howard Taft, but the two did not have a close relationship. Taft mistrusted Pinchot, whom the chief executive thought was “a strange combination” of a “socialist and spiritualist.” Taft thought Pinchot was “capable of any extreme act,” and the president frowned upon those occasions when he felt the chief forester was acting beyond his authority under the law.

Eventually, Gifford Pinchot intervened on behalf of an Interior Department employee who was upset about Secretary Richard Ballinger having approved claims to mine disputed coal in Alaska. Pinchot was very vocal in his criticisms of Secretary Ballinger and was eventually fired by President Taft for insubordination.

Pinchot sought out former President Theodore Roosevelt when the two were traveling in Europe and discussed his dismissal. Gifford Pinchot delightedly bolted the Republican Party to become a Progressive and gleefully supported the candidacy of Theodore Roosevelt against William Howard Taft. Splitting the Republican Party asunder, neither won, and allowed Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson win the election with a plurality of the vote.

Pinchot continued to affiliate with the Progressive Party and was the nominee against GOP incumbent U.S. Senator Boies Penrose in the 1914 election. Senator Penrose won easily, although Pinchot tallied more votes than the Democratic nominee.

Like most of the others who followed Theodore Roosevelt out of the Republican Party, they followed him back into the GOP. Pinchot supported the candidacy of Warren Harding in 1920. There was no appointment to any office forthcoming from the Harding administration, but Pinchot did receive an appointment from Governor William Sproul to serve as the head of Pennsylvania’s forest commission in 1920. Working with his customary zeal, Pinchot quickly lobbied the legislature successfully for more money, weeded out political appointees and replaced them with professionals, and streamlined the effectiveness of the commission.

Pinchot announced his candidacy to become governor of Pennsylvania when he entered the Republican primary in 1922. Pinchot only narrowly edged out George Alter for the GOP nomination by just over 9,000 votes out more than a million cast. In the general election, Gifford Pinchot won by more than 250,000 votes, tallying more than 56% of the ballots cast.

Governor Pinchot was faced with a bitter coal strike during the first year he was in office. He worked to settle it as quickly as possible, summoning both owners and workers to the state capitol. The governor located the mine owners in one room and the workers and their representatives in another. The tall and lanky governor shuttled back and forth between the rooms as he tried to negotiate an agreement. Pinchot took elements from both sides and helped to craft a compromise which both sides eventually accepted, albeit both complained they had been done an injustice. Perhaps it was indicative of a truly fair settlement.

“I made no threat whatever,” Pinchot told newsmen. “The settlement was brought about by my insistence that the principles proposed were right and just.” Pinchot had helped to end the strike just one week after it had started.

When Gifford Pinchot assumed office as governor, the state was operating with a deficit in its treasury of some $32 million, a considerable sum for the time. Pinchot worked hard to balance the books and by the time he left office, the governor had Pennsylvania running in the black and left a surplus of more than $6 million.

Pinchot was viewed by some as the progressive alternative to President Calvin Coolidge, who had succeeded to the White House following the sudden death of Warren Harding. Ironically, it was Pinchot’s work with the coal strike that helped to derail his presidential ambitions. As a result of the settlement proposed by Governor Pinchot, coal prices rose steadily, which was much resented by consumers.

At the time, Pennsylvania did not allow its governors to seek a second consecutive term in office. Barred from running again, Gifford Pinchot opted to run for the United States Senate once again in 1926. The incumbent was George Wharton Pepper, a Republican who had been a very well-respected attorney who had been appointed to succeed Boies Penrose in 1922. Pepper had subsequently been elected to serve the remaining four years of Penrose’s term.

The campaign for the GOP nomination for the United States Senate quickly became a three-cornered fight between Governor Pinchot, Senator Pepper and Congressman William S. Vare of Philadelphia. Vare was the boss of the enormously powerful Philadelphia machine, which could produce astonishingly large majorities for its favored candidates.

Pinchot ran a distant third while Senator Pepper lost the GOP nomination to Congressman Vare by 81,000 votes. Vare only carried one county outside of Philadelphia, but his majority in his hometown was quite nearly a massive 224,000 votes. Governor Pinchot refused to certify Vare’s win in the general election, pointing to instances of fraud and corruption. The expenditures by the Vare campaign and questionable results caused the Senate to refuse a seat to William S. Vare.

As Governor Pinchot gave his farewell message before the state legislature, the restless legislators suddenly snapped to attention when the chief executive mentioned “gangs.” “After four years in a position to learn the facts, I am going out of office with the most hearty contempt not only for the morals and intentions but also for the minds of the gang politicians of Pennsylvania,” Pinchot snapped. The governor denounced the “Mellon machine in Pittsburgh” and the “Mitten machine in Philadelphia” and said the machines were rife with “men who depend for the living and their power, on liquor, crime, vice.” “These are the men the magnates buy,” Pinchot sniffed. “These are the men they protect from time to time against the revolt of honest citizens who would otherwise destroy them.”

As for the machine bearing the name of Andrew Mellon, the treasury secretary under presidents Harding and Coolidge, Governor Pinchot charged ordinarily respectable people “shut their eyes and make common cause with gangsters, vote thieves, dive keepers, criminals and harlots, because of the social and financial eminence of the Mellon name.”

For his comments, the governor received a smattering of applause and a torrent of jeers and hisses from legislators. Four years later, Pinchot was back once again campaigning to recapture the governor’s office. To the horror of the old guard, Pinchot won the primary election and the Republican nomination. While Pinchot carried Pittsburgh in the general election, the Philadelphia machine refused to back the former governor and supported the Democratic nominee, John Hemphill. The result was a very narrow win for Gifford Pinchot, who won with 50.77% of the vote. Part of the small margin of Pinchot’s win was the increasing difficulty imposed upon people by the effects of the Great Depression.

During his second term, Pinchot once again wrestled with the budget while doing his best to help those who were suffering intensely due to the Depression. Governor Pinchot prodded the legislature to approve money to help the indigent and poor and worked during his last two years in office with President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration.

Term-limited once again in 1934, Gifford Pinchot made a third bid for a seat in the United States Senate, challenging incumbent Senator David A. Reed, one of the louder voices against the New Deal in the chamber. Reed won the GOP nomination by almost 99,000 votes.

Gifford Pinchot’s last hurrah in elective politics came during the 1938 election when he sought once again to return to the governor’s mansion. Bitterly opposed by the few remnants of the machines, conservatives and the old guard, Pinchot campaigned gamely but lost decisively to Lieutenant Governor Arthur James.

For the rest of his life, Gifford Pinchot traded verbal blows with curmudgeonly Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes and remained active until he died on October 4, 1946, at age 81, a victim of leukemia.

© 2026 Ray Hill