Tennessee’s Junior U.S. Senator: Nathan L. Bachman

By Ray Hill

There was a time when successful politicians knew how to scrap, but were also able to entertain and charm. Evidently, that time has come and gone. One excellent example of such a politician was Nathan Lynn Bachman of Chattanooga. Scholarly with a highly developed sense of humor, as well as a liking for fun, Bachman was married to Pearl Duke, of the fabulously wealthy North Carolina tobacco and power family. The couple lived atop Signal Mountain and had only one child, a daughter. The Bachmans occupied a very nice home, surrounded by 70 acres, which one writer described as “a dream of a country gentleman’s home.” There in the “old-fashioned” living room of their house, Nathan Bachman kept an oil painting of “Old John,” a Black man who had taken care of him as a child. Long since dead, Old John’s portrait hung in a prominent place as long as Nathan Bachman lived. Behind the house was a large garden, and much of the produce was given to his neighbors on Signal Mountain, whom he called “the old settlers.” There were kennels of hunting dogs, of which the senator was exceedingly fond, as well as orchards.

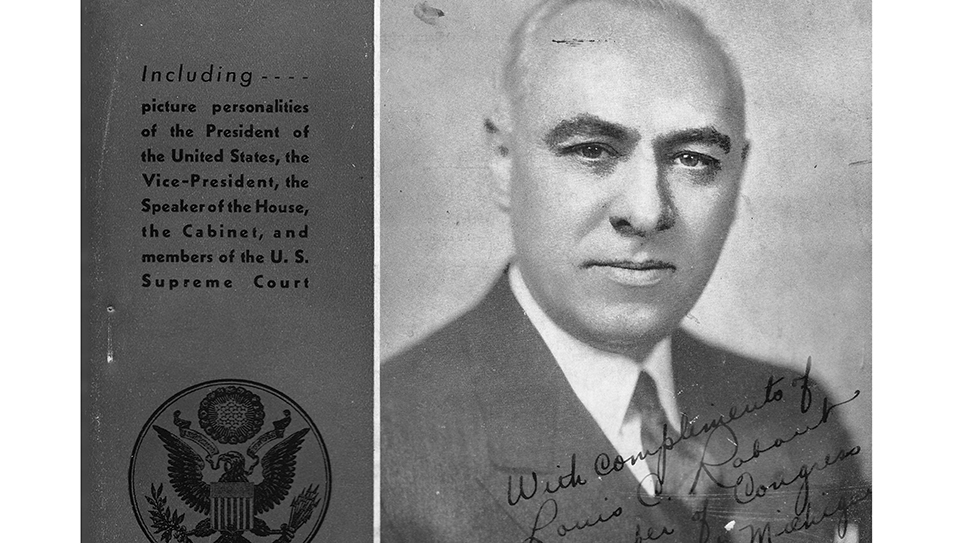

Nathan Bachman was affable, polite and yet disarmingly homespun. Invariably attired in a suit, white shirt and black bowtie, which he wore tucked under the points of his collar, Bachman was said to have never owned a vest. Bachman favored a pearl-gray, wide-brimmed western-style hat, which was custom-made for him.

Yet Bachman enjoyed being very casual. Once Pearl Bachman was giving a dinner party and had invited the famed attorney Clarence Darrow, as well as a newspaperman from Washington, D.C. The newspaperman was beside himself for not having brought a tuxedo to Tennessee and sheepishly turned down the invitation to the dinner party. The other guests found Nathan Bachman sitting in his yard wearing a plain shirt, corduroy pants and a pair of brogans. When told about the reporter who had not shown up because he had no tuxedo, nobody laughed harder than Bachman.

As a storyteller, Nathan Bachman had few peers and was much sought out for his company, and he was one of Vice President John Nance Garner’s favorite companions in Washington, D.C. The two could usually be found attending baseball games together in the Capitol city. High-spirited and speaking with a soft drawl, Bachman’s storytelling made him a much-in-demand speaker and toastmaster.

Known as “Nath” or “Nate” to friends, Bachman seemed to have an endless supply of stories that he could dole out like a gum drop for just about any occasion. There might be those who disagreed with Senator Bachman about an issue, but there was hardly anybody in Tennessee who did not like him personally.

Ruth Spencer remembered Nathan Bachman as a warm-hearted and genuine man. Mrs. Spencer was speaking at an event and describing a book she had read recently, which she said was “full of sunshine and shadows, laughter and pathos.” She had been quite nervous speaking before Bachman, whom she knew to be a man of learning, “wide experience and culture.” Mrs. Spencer was very surprised when the senator approached her afterward, his cheeks still wet from his tears, to tell her, “That was a beautiful story.” Ruth Spencer believed Nathan Bachman forever kept a childlike simplicity in his own heart.

Nathan Bachman attended at least five colleges before setting out to earn a law degree. Bachman went to the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga before moving on to the University of Virginia, where he earned his law degree. Nathan Bachman also attended Washington & Lee University and Central University. Evidently, Bachman’s penchant for pranks caused him some occasional anguish, as most college administrators failed to see the humor in his jokes. “I guess I had a harder time than any other boy in the world finding a college president who suited me,” Bachman recalled years later. “But I just had to find one who was competent.”

While attending Southwestern Presbyterian University, which was then located in Clarksville, Tennessee, Bachman had been confined to his rooms for some infraction of the rules. Chaffing at his involuntary confinement, Bachman decided he couldn’t stand it a moment longer, especially as there was a dance he longed to attend.

Bachman convinced a local mortician to give him the loan of four white horses and a carriage with which he could convey his young lady to the dance. If he received any further discipline for flouting his punishment, it has been lost to history. College friends also recalled an incident where Bachman had a baby calf in his room. When queried about the incidents in later life, the senator laughed and said, “The statutes of limitations run against my recollections.”

Despite his fondness for jokes and pranks, Nathan L. Bachman had an excellent work ethic. Bachman always remembered his father having “had a great antipathy to loafing.” “During vacations, I had to get a job or go to the farm – – – and one was as bad as the other,” Bachman laughed.

Named city attorney for Chattanooga in 1906, Bachman had only been out of law school for three years. Bachman went into private practice in 1908 and, in 1912, was elected a judge of the circuit court. Six years later, Bachman was elected to the Tennessee State Supreme Court.

Bachman won a well-deserved reputation as a fair and thoughtful jurist, but he did not seek reelection in 1924, opting instead to seek election to the United States Senate. The Senate seat was occupied by the crusty and cantankerous John Knight Shields of Grainger County, who had been the last man to be elected by the state legislature to represent Tennessee in the United States Senate. Shields had won a difficult reelection battle in 1918 when he had been challenged in the Democratic primary by Governor Tom Rye. Senator Kenneth McKellar had convinced President Woodrow Wilson not to send a letter for publication condemning Shields as an enemy of the administration that year. McKellar was astonished when Shields remained as firm in his opposition to Wilson’s attempt to see America participate in the League of Nations.

Shields was opposed by General Lawrence D. Tyson, a very wealthy businessman who had bought the Knoxville Sentinel to further his political ambitions. Tyson spent freely of his fortune and the three-cornered race was hard fought. Woodrow Wilson had written the letter he had not in 1918, and it was published after his death, helping to defeat Senator John Knight Shields from the grave. The former president remained popular in Tennessee. Tyson won the Democratic nomination; Senator Shields ran second, and Nathan Bachman was in third place. Bachman had carried two of Tennessee’s big urban counties; his showing in his native Hamilton County was indicative of his overwhelming popularity. Bachman tallied 8,223 votes to a combined total of 1,372 for Shields and Tyson. Nathan Bachman also carried Shelby County by a few hundred votes.

Bachman had a happy home life and cheerfully returned to the practice of law. When Cordell Hull was selected to be Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of state, it necessitated an appointment to fill the vacancy caused by Hull’s resignation. Newly elected Governor Hill McAlister appointed Nathan Bachman on February 28, 1933. Governor McAlister almost certainly made the appointment after consultation with Tennessee’s senior United States senator, Kenneth McKellar.

“He is a lifelong Democrat, a distinguished lawyer and a public man of wide experience,” Governor McAlister said of Bachman in making the appointment to the Senate. “I have every confidence his views on state and national political issues will cause him to promptly ally himself with President Roosevelt on all matters.”

For the next four years, the duo of McKellar and Bachman worked in tandem for the people of Tennessee and got along exceptionally well. Like most freshmen senators, Nathan Bachman said little his first year in the Senate, concentrating upon his committee work and looking after Tennessee’s interests. When friends asked about his being so quiet, Bachman explained, “The veterans up here expect newcomers to keep quiet for a while.”

When Nathan L. Bachman represented Tennessee in the United States Senate, it was still a largely agrarian state. Senator Bachman was keenly interested in the welfare of Volunteer State farmers. “I am probably more interested in the restoration of agriculture than any other one thing,” Bachman said. “There can never be any real prosperity until agriculture is stabilized – – – that is essential.”

Bachman had to run in the 1934 special election to fill the remaining two years of Cordell Hull’s term, and McKellar was running for his fourth term. Congressman Gordon Browning, who had served for twelve years in the House of Representatives, like many congressmen, very much wanted a promotion to the U.S. Senate. Browning went on a “listening tour” of Tennessee to consider a race against the formidable McKellar. The congressman didn’t like what he heard and quickly concluded he could not beat McKellar. Browning, an impulsive man, then stunned most everybody when he announced he would run against Nathan Bachman.

Senator McKellar swung in behind his junior colleague and was effective enough to cause Browning to complain that Bachman’s campaign was being run out of McKellar’s Washington office. Another Browning complaint was that McKellar had two votes in the Senate, saying Bachman was content to follow the senior senator’s lead. Bachman proved to be an effective campaigner and won the Democratic primary decisively. Browning had not embarrassed himself and was elected governor two years later.

Both Bachman and McKellar were avid supporters of the Tennessee Valley Authority. McKellar was a stalwart of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and Senator Bachman was highly supportive of the president’s program as well.

When Bachman had to face the people of Tennessee once again in 1936 to seek his first full six-year term, he faced only nuisance opposition from political gadfly and perennial candidate Dr. John R. Neal. Senator Bachman carried every county in Tennessee.

Nathan L. Bachman never had the opportunity to rust out. Safely reelected to a new six-year term in the United States Senate, the 58-year-old Bachman had served three months of his new term when he began to feel poorly. The senator’s doctor said Bachman had been “a little ailing” recently, which worried the senator’s wife. Mrs. Bachman intended to return home to Tennessee from Washington, where they lived in an apartment at one of Washington’s better hotels. Pearl Bachman fretted about leaving her ailing husband, but the senator was improving and insisted she go home, especially as he had a nurse with him. Mrs. Bachman left for Tennessee by automobile on Friday, April 23, 1937, around 11 a.m. That same afternoon, the senator’s doctor, Russell Verbrycke, stopped by to check on his patient. The doctor was unhappy with what he saw and advised Senator Bachman to go to the hospital. Bachman chose not to go, and later that evening, Miss Mary Site, the senator’s nurse, found Bachman in distress and called his doctor. Dr. Russell Verbrycke was on his way back to the senator’s apartment when Nathan L. Bachman’s heart stopped beating, the victim of a heart attack.

Governor Gordon Browning’s comment following the death of Nathan Bachman summed up the feelings of the people of Tennessee, as well as those of official Washington. “The whole state is shocked,” Browning said.

E. H. Crump lamented the loss of Nathan Bachman. “Senator Bachman was one of the popular members of the Senate,” Crump said. “He had been there long enough to become a useful man for Tennessee. I regret his passing.”

The death of Senator Nathan Bachman deprived Tennessee of a potentially highly effective senator, but Bachman passed at the peak of his powers and personal popularity.

© 2025 Ray Hill