Costigan of Colorado

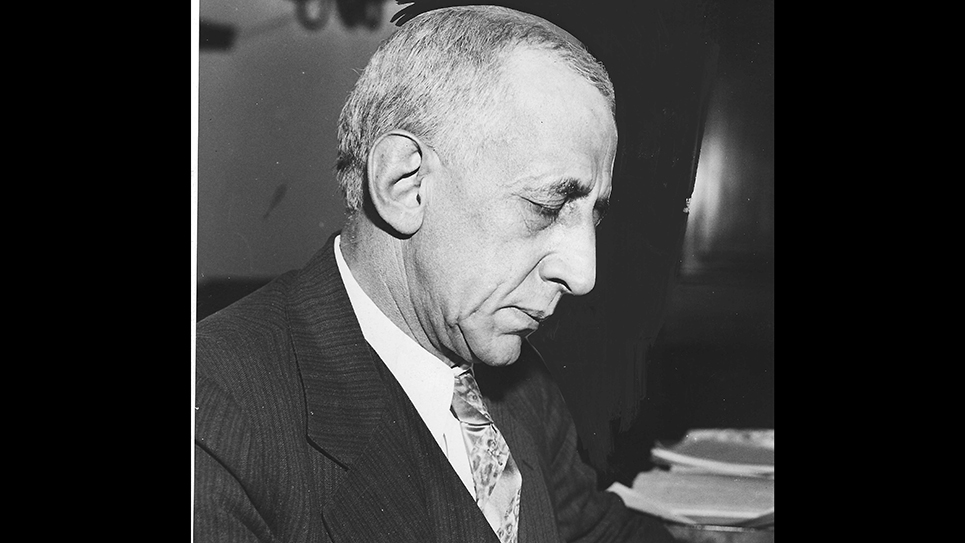

Edward P. Costigan

By Ray Hill

The most widely read news magazine in the world, TIME, aptly noted, “One way to spoil a party of which you disapprove is to leave it, making a disturbance as you go.” That was the description TIME used to report the resignation of Edward Prentiss Costigan from the Federal Tariff Commission. At the time of his resignation, Costigan was the longest-serving member of the Federal Tariff Commission after eleven years of service. Edward Costigan was also the last person serving on the FTC who had been appointed by President Woodrow Wilson. Costigan had been a progressive Republican who had supported Theodore Roosevelt’s third-party candidacy in 1912. After a failed gubernatorial campaign as a “Progressive” in 1914, Costigan became a Democrat. Wilson appointed Costigan after his party conversion in 1916. Edward Costigan liked to say he was “a Progressive with Republican antecedents and Democratic consequences.”

Thin and solemn, Edward P. Costigan spent the better part of his life pulling the teeth of whatever injustices he considered to be moral monsters. Nor did it matter the size, shape or form as far as Edward Costigan was concerned. What someone else thought was a molehill, Costigan considered to be a mountain for the gentleman tended to view things in stark black and white terms. If Edward Costigan ever saw shades of gray, it is almost impossible to tell. To Costigan, every issue was one of morality – – – his own – – – versus evil. During Edward P. Costigan’s time on the Federal Tariff Commission, the Republicans favored protectionism and high tariffs while Democrats usually supported lower tariffs. To Edward Costigan, high tariffs were evil. In his letter of resignation, Costigan lambasted President Calvin Coolidge and his fellow commissioners. Costigan bitterly assailed what he wrote was “the manipulation of the commission since 1922,” which he considered to be “but part of the total picture of present-day Washington.” Costigan acidly penned that it would doubtless be “an era which history may yet summarize as the ‘Age of Daugherty, Fall and Sinclair.’” Daugherty was the attorney general appointed by the late President Warren Harding, and the reference to “Fall” was Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall, who had left office under serious charges of corruption in office amid the Teapot Dome scandal and later went to prison. Harry Sinclair was the president of Sinclair Oil, who had given dubious “loans” to Secretary Fall and had been the beneficiary of oil leases.

Edward P. Costigan assailed his colleague on the Federal Trade Commission, Thomas O. Marvin, a Boston Republican who had been appointed by Harding, as a “lobbyist.” Indeed, Marvin had been a lobbyist for the wool industry when he had been appointed. What Ed Costigan objected to was Marvin’s utter devotion to high tariffs. Costigan said Marvin was “tireless and fanatical” in his views and complained that President Coolidge had exercised a prerogative that every chief executive used, namely, to remove those appointees who did not share his own views.

Following his resignation from the FTC, Costigan went home, started up his law practice and thought about seeking public office. In 1930, Costigan sought a seat in the United States Senate when incumbent Lawrence C. Phipps chose not to run again. Ed Costigan won a majority in a three-way primary to become the Democratic nominee. The general election had not only Republican and Democratic candidates on the ballot, but also candidates representing the Farmer-Labor, Socialist, Communist, Liberal and Commonwealth parties. Costigan won the fall election easily with quite nearly 56% of the vote.

Once inside the United States Senate, Edward Costigan was recognized as an insurgent Democrat. The Colorado senator’s progressive views had not changed an iota. Never before had the federal government considered using taxpayer dollars to feed hungry people. In 1932, that changed when Robert LaFollette Jr., a progressive Republican from Wisconsin, and Costigan sponsored a “relief” bill, which provided money for families suffering from the want and economic disaster wrought by the Great Depression. President Herbert Hoover was adamantly opposed to relief being given directly to the people. Costigan and LaFollette had brought a veritable parade of witnesses from across the country who proceeded to testify that ordinary charitable organizations had buckled under the weight of the suffering inflicted by the Depression.

Edward P. Costigan was recognized by some as the first “New Dealer” in the country before Franklin Roosevelt’s administration came into office. Costigan had angrily told his senatorial colleagues, “Lives and happiness of human beings are a proper concern of our country.” When direct relief passed Congress, Costigan exulted that “a great principle is being established.”

“The issue may be postponed by a reluctant timid or suppliant majority of the Senate, driven, hypnotized by the allurements or hostility of the White House, financial or industrial interests,” Costigan barked on the floor of the Senate. “It cannot, however, be evaded … It involves nothing less than the inalienable right of American citizens to life!”

Senator LaFollette coolly observed his colleagues and opined that unless action were taken and soon, “there would be some empty seats in the next Senate.” The Republicans in the Senate, realizing the House with a majority of Democrats, would have the final say, decided to let the Democrats in the Senate chew on one another.

Senator Costigan was not so idealistic that he ignored the needs of his state. Costigan was the Senate sponsor of the Jones-Costigan Act, which provided direct payments from the government to sugar beet growers. As a member of the U.S. Senate, Edward Costigan was a supporter of the Roosevelt Administration and the New Deal, as well as organized labor. Costigan had long been identified with labor, as he had been the attorney for the United Mine Workers in 1914 when several men were accused of murder during strike protests in several southern Colorado towns. Edward Costigan finally won an acquittal of all the defendants in 1916.

Edward Costigan was a very close friend of Miss Josephine Roche, who owned one of the most successful coal companies in Colorado and was a big producer in the state. Miss Roche was a devout Democrat and liberal and was known for plowing the company’s profits back into the business. Josephine Roche challenged incumbent Governor Ed Johnson inside the 1934 Democratic primary with the support of Senator Costigan. Johnson was a Democrat, but a far more conservative one than either Miss Roche or Costigan. Johnson won the contest decisively, albeit not overwhelmingly.

Senator Costigan joined with another liberal, Robert F. Wagner of New York, to sponsor anti-lynching legislation in 1933. As a boy of ten, Ed Costigan had seen a man and woman brutally whipped publicly, which gave him a revulsion for mob violence he carried for the rest of his life. Costigan had drafted the bill, which sought to impose penalties of fines or imprisonment upon state and local officials who failed to prevent the injury or death of someone at the hands of a lynch mob. Supporters of states’ rights and Southern Democrats immediately began a filibuster, and Senator Costigan and his allies could not summon the votes necessary to break the filibuster.

In Colorado, Senator Costigan was the acknowledged leader of the liberal faction and recognized as a leader in the New Deal administration. The administration of President Roosevelt doled out patronage to Senator Costigan, and several of those holding federal jobs in the Centennial State were looking to eliminate Congressman Fred Cummings in the 1934 election. Cummings was adjudged to be lukewarm to the New Deal by many of the president’s supporters. The Fort Collins Coloradan grumbled that Costigan’s patronage had helped the senator to assemble a formidable political machine. In an editorial, the Coloradan hailed the defeat of Josephine Roche for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination as the end of Senator Costigan. The bitter contest for governor had been largely pitched along lines of liberal versus conservative, New Dealer versus independent, and Johnson had won. The newspaper editorial sneered that Costigan had managed to build a political machine while “preaching social justice and political honesty.”

Likewise, the increasing attacks from Governor Johnson throughout 1935 signaled his intention to run in the primary against Senator Costigan in 1936. The governor complained to President Roosevelt about Costigan while making a particular state appointment that political observers saw as a move by the governor to bring a key Costigan supporter to his own side. Senator Costigan’s support of his friend Miss Roche had certainly widened the growing breach between him and the governor. The rivalry between the competing factions of Colorado’s Democratic Party would remain intense for several decades.

Senator Edward P. Costigan was 62 years old in 1936 when he had to decide whether or not to seek another six-year term. Costigan knew he was almost certain to face a difficult race as Governor Ed Johnson was gearing up to run against him inside the Democratic primary. Johnson was highly popular in Colorado and a formidable political figure with a large personal following. The governor had not been shy at all about criticizing Costigan’s votes in Washington. Newspapers at the time of his death noted the senator’s health “had broken” before his term of office had ended. Costigan was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where he remained for months. Every indication is that Edward P. Costigan had suffered some kind of nervous breakdown. Costigan had been absent from the Senate since March 20, 1936.

In April 1936, the senator’s office released a statement saying Costigan would not be a candidate for reelection due to his ill health. F. Lee Johnson, secretary (chief of staff) to Senator Costigan, offered a brief explanation, saying, “He is suffering from overwork and exhaustion.” Reporters asked if the senator had recently become worse, and Johnson refused to make any further statement, nor would he say exactly where Costigan was resting. Costigan had driven south to Florida, although the senator never said where he and his wife intended to stay.

Senator Costigan’s announcement that he would not run again caught friend and foe alike by surprise. Governor Ed Johnson was visibly surprised when reporters told him the news of the senator’s decision. Asked about his own candidacy, Johnson said he was sorry for Costigan’s illness but had nothing else to say.

Costigan was still ill following the November elections, and it was reported he was improving in early December, both “mentally and physically.” Senator and Mrs. Costigan were seen walking across the hospital grounds most days, and friends were able to visit. One veteran reporter wrote Senator Costigan was “able to discuss questions with a great deal of understanding.” Mabel Costigan had been elected as a presidential elector in the 1936 election, and she had notified the Colorado secretary of state that she would not be able to return home to Colorado to cast her vote, as she wished to remain with her husband.

The following January, days after her husband’s term in the Senate ended, it was announced she had been appointed as the administrative assistant to Richard P. Brown, an assistant executive director in the National Youth Administration. Walter Walker’s Daily Sentinel hailed Mrs. Costigan’s appointment as the publisher wrote she was “an exceedingly well-qualified woman” who would bring “keen enthusiasm” to her job. The newspaper publisher and former U.S. senator noted Mrs. Costigan had been an invaluable aide to her husband throughout his career.

As Mabel Costigan began her new job, the former senator became so ill that his condition was declared critical. Evidently, Edward Costigan was suffering from a blood infection, and his temperature hovered around 104 degrees. A “new drug” was administered to Costigan, which lowered his fever.

Edward P. Costigan and his wife Mabel returned to Denver, where the former senator lived for another year before his health gave way completely. Costigan caught a cold, which rapidly developed into lobar pneumonia, which brought on a heart attack.

Costigan remained a symbol to fellow liberals for decades in Colorado.

© 2025 Ray Hill