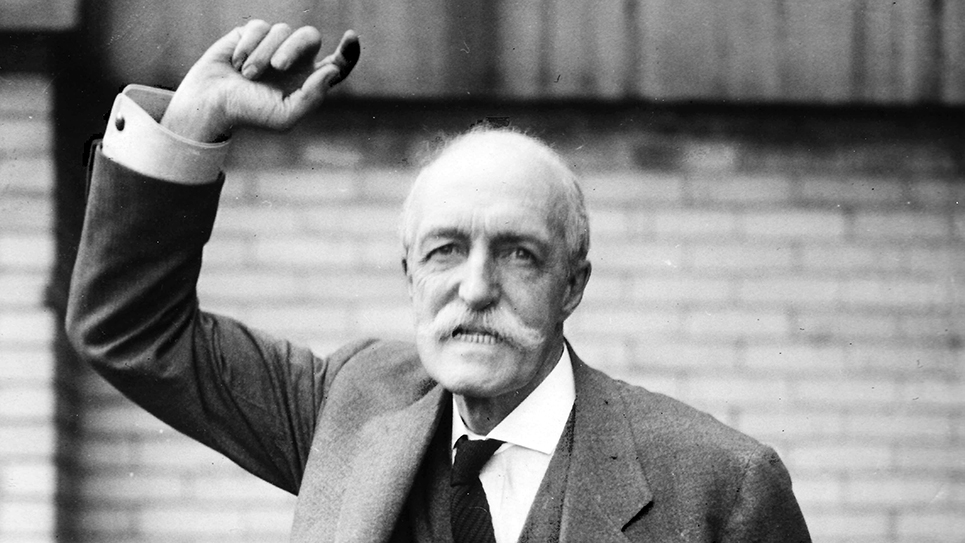

Homer T. Bone of Washington

By Ray Hill

Homer T. Bone served just under twelve years in the United States Senate and sat on the federal bench as a judge of the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals from 1944 until his death in 1970. A man devoted to his wife and son, Homer Bone’s passions included locomotives and oysters, which he sometimes enjoyed for breakfast. Homer and Blanche Bone lived in an outwardly modest-appearing white frame cottage, which sat atop a green hill in a neighborhood once known as “Little Germany” in Tacoma. In reality, the house was quite large and spacious with a sweeping view of the city below and the sea beyond.

Bone was a small man of neat appearance and possessed a profoundly sardonic wit, which he used freely. Once Senator Bone took a fresh salmon up to the Senate Press Gallery for the delectation of the waiting newsmen, who proved unable to undo the wire wrapping around the case. “Do you mean that with all the knockers around here, you fellows haven’t got a hammer?” Homer Bone wondered.

The most widely read news magazine in the world, TIME, described Senator Bone as “a round-shouldered, kindly little man with a gloomy viewpoint.” Whenever the senator was discussing world events, evidently Bone frequently acknowledged to his listener, “This is a dark and somber picture.”

Millions of modern Americans owe Senator Homer T. Bone a word of thanks. The Washington senator worked tirelessly on behalf of the creation and financing of a national institute for cancer research. Aided by a young congressman from his home state, Warren Magnuson, and by Senator Matthew M. Neely of West Virginia, who had lost three fingers to the dread disease, Bone personally made it a point to stop and seek support from each of his 95 colleagues. Perhaps as many as half of the leading cancer specialists in America testified on behalf of Bone’s bill.

TIME recorded that the grounds of the new institute had been donated by Luke Wilson, the heir to a haberdashery fortune, and his wife, who was an heir to the Woodward & Lothrop department stores. Luke Wilson never lived to see Homer Bone’s bill passed, dying just a few weeks before President Roosevelt signed it into law. Wilson died of cancer on July 19, 1937. It was Homer T. Bone who laid the cornerstone for the National Institute for Cancer Research that same year.

Years later, when the judge was honored by the City of Hope in San Francisco, Bone recalled, “Too many of my friends had died of cancer. This brought home to me the magnitude of the cancer problem, and I determined that the Government should do something about it.”

So, too was the senator the author of the Bone Power Act, which allowed the creation of public utility districts for the first time. Bone was oftentimes referred to in the press as the “Father of Public Power.”

As a boy, Bone had fallen down an elevator shaft, resulting in an injury to his neck, which remained rather stiff. According to TIME magazine, Homer Truett Bone sometimes looked “as rigid as his principles.” Bone recalled the incident for Ann Guffin, a writer for the Tacoma News Tribune. “I was a youngster working in the Tacoma Post Office at the time I received my injury in the elevator.” It was January 1904 when Homer Bone was headed for his brother’s offices, which were located in the Bernice Building. A “young and robust” fellow, Guffin wrote Bone stepped out at the fifth floor “when the allegedly defective elevator manned by an alleged equally inept operator, shot up, catching him in the open door.” Ann Guffin wrote, Bone “was pinned mercilessly and crushed into a heap on the floor of the elevator cage.” According to court documents and what Judge Bone shared himself, it took a doctor over an hour to revive him. Bone filed suit and won a $3,000 judgment.

Judge Bone wrote a letter to a reporter for the Franklin, Indiana Evening Star, recalling, “My father served in the Union Army throughout the Civil War as a soldier in the 7th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. In 1862, he was a prisoner of the Confederacy for six months at the Belle Island Prison in the James River near Richmond, Va.” The judge remained modest, abruptly writing he had held various public positions, “but probably any more specific information would be surplusage.”

A loud and strong advocate for public power, Bone began the practice of law in 1911 and sought office unsuccessfully under a number of banners, including that of the Socialist Party. Bone was elected to the Washington state legislature as a member of the Farmer-Labor Party for a single term. Bone sought to win a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Farmer-Labor candidate in 1920 and was unsuccessful. Oddly, Bone switched to the Republican Party in 1928 and ran against Congressman Albert Johnson yet again. Bone only narrowly lost the primary by 1,550 votes. For the rest of his life, Homer Bone maintained he lost the GOP primary to Congressman Johnson because on the day of the election, Tacoma’s streetcar line mysteriously lost power, leaving voters of more modest means unable to get to the polls.

Homer Bone was a good attorney and was the corporation counsel for the Port of Tacoma from 1918 until 1932, when he resigned. A forceful speaker, Bone was quite capable of spewing vitriol if angered.

By 1932, Bone was a Democrat and was running against Senator Wesley L. Jones, a veteran member of Congress who had served five terms as Washington state’s congressman-at-large and won a seat in the United States Senate in 1908, being elected by the state legislature. Jones was reelected by the voters in 1914, 1920 and 1926. Wesley L. Jones was an institution in the politics of Washington state, but the 69-year-old senator was not universally popular. Worse still for the incumbent was the stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression. Politics and voting patterns changed dramatically and forever in some instances. The residents of Washington state looked to Democratic presidential nominee Franklin Roosevelt as a source of hope in a world that was full of misery and despair.

The Democratic ticket routed the Republicans, and Homer Bone won election to the U.S. Senate, carrying every county in the state. Bone carried his home of Pierce County with better than 67% of the vote and won an overall victory of just over 60% of the vote. Senator Jones polled a dismal 32% with minor candidates making up the rest. The shock of his defeat was apparently too much for Senator Jones. Exhausted after his reelection campaign, Jones went to rest in a sanitarium and died of a heart attack on November 19, 1932.

Homer Bone entered the U.S. Senate, where he loyally supported most of President Roosevelt’s New Deal program. The peppery Homer T. Bone bristled at the notion he was a rubber stamp for anyone and that included Franklin D. Roosevelt. Senator Bone did not hesitate to oppose the Roosevelt Administration when he disagreed. When FDR was openly backing Alben Barkley of Kentucky to become Senate majority leader, Bone supported Mississippi’s Pat Harrison, who lost by a single vote. Bone was not an avid supporter of Roosevelt’s foreign policy, especially as the Second World War began to rage. Senator Bone advocated for America remaining neutral and out of the war.

When the Senate wrestled with FDR’s Lend-Lease Bill, Senator Homer Bone demanded on the floor of the Senate to know what could possibly be worse than war? Senator Warren Austin, a Republican from Vermont, solemnly replied, “I say that a world enslaved to Hitler is worse than war, and worse than death. A country whose boys will not go out and fight to save Christianity in the world and to save the principle of freedom from ruthless destruction by a fiend – – – well, we do not find such boys in America.” Even Homer Bone had no retort to that.

By the time Senator Bone sought a second term in 1938, he had spent little or nothing on his reelection bid except for the cost of gas for his personal automobile. The senator even returned a check for $500 to the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, saying he didn’t propose to spend anything on his campaign. Bone had tallied more than 243,000 votes while a large field of opponents won a combined total of 196,000. Bone easily swept aside the GOP challenger in the general election. Homer T. Bone had become arguably the single most popular local politician in the state of Washington.

By 1944, Homer Bone had tired of the vagaries of politics, realizing the longer he remained in the Senate, the more difficult it would be to leave it. Nor did Bone relish the idea of campaigning for office every six years and having to raise the money necessary to win. Senator Bone was weary of making the long journey back to Washington state from Washington, D.C., at a time before jet travel. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt offered him a seat on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, Bone accepted it. As is almost always the case with a colleague or former colleague, the Senate rapidly confirmed Bone’s nomination.

Judge Bone lost his wife, Blanche, who had been suffering from what newspapers at the time referred to as a “long illness,” on September 1, 1955. Blanche Bone died of cancer at age fifty-eight. Two months later, Judge Bone announced he was assuming “senior status” as a federal judge. That particular status allowed judges to retire but also continue to hear cases, doing “substantial work,” which allowed them to collect their full salaries of $25,000 ($284,000 today). Homer Bone was 72 years old at the time he announced his retirement.

One assignment as a “senior judge” took the 77-year-old Homer T. Bone to Honolulu, Hawaii, where he sat on the federal bench for two weeks. The Honolulu Star Bulletin marveled at the “spry” judge “who keeps young by working.” Evidently, Judge Bone had gone to Hawaii to preside over trials where local federal judges had recused themselves. One trial involved a failed candidate for the state legislature who was indicted by a grand jury, and Judge Bone issued a bench warrant for the person’s arrest.

Bone opened up a private practice, as well as continuing to sit on the bench until 1968. Throughout the decade of the 1960s, Bone was apparently in remarkably good health, especially for his age. Bone was honored in San Francisco by the local cancer society and had never forgotten his late wife’s suffering and struggles; the judge still traveled to speak to local organizations on the topic of cancer research and advances in treatment of the dread disease. In 1962, the judge was the honorary chairman of the fundraising drive for the City of Hope in San Francisco. That same year, Judge Bone was honored in Seattle by the American Cancer Society, which presented him with the “Man Against Cancer” special award. Among those taking part in the ceremonies was actor William Gargan, who had lost his voice to cancer. After six torturous months of rehabilitation and effort, Gargan regained his ability to speak. Following his experience, William Gargan made time to speak to groups throughout the country on behalf of the American Cancer Society and its cancer-prevention programs.

The Washington House of Representatives voted in 1963 to send a resolution to the Evergreen State’s congressional delegation asking that a dam be named for Homer Bone, but as the judge was still living and healthy, nothing ever came of the idea.

In 1968, at age 85, Homer T. Bone finally fully retired and left San Francisco, returning home to Tacoma. After a long and highly productive life, Homer Bone died two years later on March 11, 1970.

© 2025 Ray Hill