Iowa’s Cantankerous Congressman

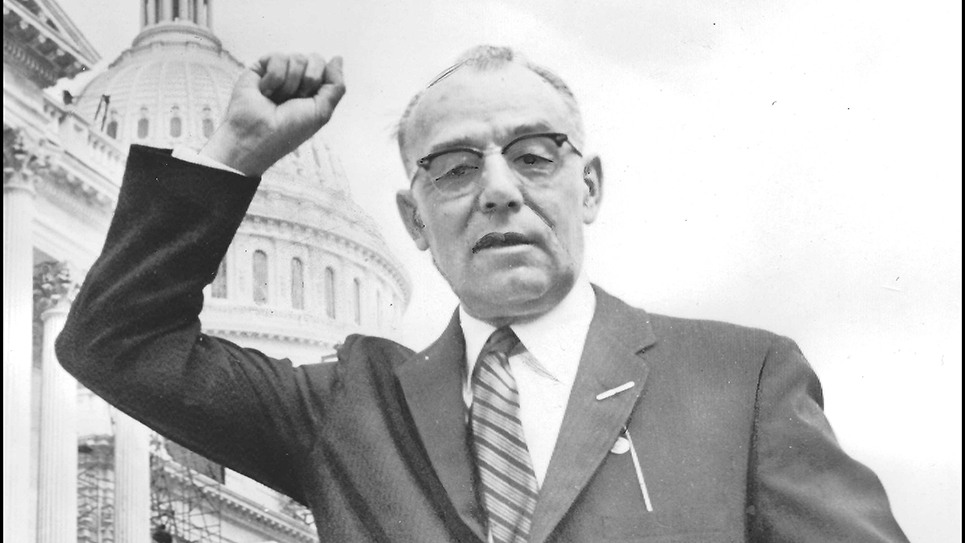

Harold Royce “H. R.” Gross

By Ray Hill

It is fair to say there was not a speck of get-along-go-along in the character of Harold Royce Gross, a former newscaster who spent 26 years in the U.S. House of Representatives representing the Third Congressional District of Iowa. Gross was as anti-establishment as it was possible to be, and the people of the Third District rewarded him by giving him huge majorities in every election save one. Only once did H. R. Gross face a close election contest inside his congressional district. Gross had no catalogue of bills passed bearing his name; in fact, there was no piece of legislation he sponsored or cosponsored that ever passed the Congress. Yet nobody could accuse H. R. Gross of absenteeism or not doing his job. The congressman from Iowa was a force to be reckoned with, one who routinely questioned governmental expenditures. To some, H. R. Gross was the “Abominable No-Man” of Washington; to others, the Iowan was the “Watchdog of the Treasury,” or the “Taxpayer’s Best Friend.”

Throughout his long congressional career, H. R. Gross was called a good many things. The most widely read news magazine of its day, TIME, once labeled the Iowa congressman “The Useful Pest.” A reporter for TIME gleefully reported the 5’6, 135-pound Gross stepping into the well of a nearly empty House Chamber. “I am becoming more and more disturbed over the failure of the House to get down to work,” Gross barked. “This is about the most do-nothing session I have seen in my 14 years here.” The congressman from Iowa had done a little calculating, which he of course passed along to the news media. Gross had figured the House had been laboring an average of four hours a day, which came to a total of fifteen days a month. Gross pointed out that each congressman was making $126 per day ($1,295 in today’s dollars). “That’s a lot of pay for such a short workday,” Gross observed.

The reporter for TIME thought it a typical performance from the “waspish” congressman from Iowa who had embarked upon a lonely crusade “to save this country from bankruptcy.” That same reporter described Gross as “a nitpicker and a pest” who “detests Washington’s social life” and preferred watching wrestling on TV with his wife, Hazel, in their Washington, D.C., apartment, which Gross called “an oasis in a community of synthetic functions.” The reporter for TIME concluded that H. R. Gross, the “self-appointed caretaker of the congressional conscience” indeed had his “own unique value.” The writer concluded the House of Representatives needed a man like H. R. Gross in its midst, but also noted “one is probably plenty.”

The reporter was careful to state H. R. Gross was not a hypocrite and “practices what he preaches,” answering 97.1% of all House roll calls. “Unlike most Representatives, he stays on the floor between roll calls, listens carefully to debates.”

TIME acknowledged Gross had a talent for observing what others failed to see or dismissed as unimportant. It was Congressman H. R. Gross who pointed out during the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy that an Army chauffeur was ferrying Frank Sinatra and Peter Lawford throughout Washington, D.C. H. R. Gross was as apt to pick at expenditures by Republicans as he was Democrats. Congressman Gross objected when former President Dwight D. Eisenhower was restored to his rank as a five-star general. Gross demanded that Ike only be eligible to collect his $25,000 presidential pension and not the $20,543 salary for a five-star general as well.

Gross used his waspish wit to good effect, noting about the space race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, “Well, even if we don’t get to the moon first, we’ll be there first with foreign aid.” As to the need for a congressional flag, Gross wondered, “How would you fly it– above or below the squirrel tail that some people fly off their radio antennas?”

For the most part, other congressmen realized H. R. Gross was something the government and the House needed. Carl Vinson, a Georgia Democrat who chaired the powerful House Armed Services Committee, once declared, “There is really no good debate unless the gentleman from Iowa is in it.” Indulgent colleagues honored Gross by reserving House Bill 144 for the Iowa congressman every year, as 144 equals a gross.

Gerald Ford, minority leader of the U.S. House of Representatives before being tapped by President Richard Nixon to serve as vice president, once said there were three political parties in Congress: Democrats, Republicans and H. R. Gross.

Harold Royce Gross began his career as a newscaster for radio station WHO in Des Moines, Iowa. One of his fellow newscasters was Ronald Reagan. Gross had also worked as a newspaper reporter and editor. While covering the Iowa statehouse, Gross met Hazel Webster, the secretary to Iowa’s attorney general, whom he married in 1929. The couple had two sons together.

The first political campaign H. R. Gross ran was a race for the GOP nomination for governor in 1940. As might be expected with Gross, it was unconventional. Gross challenged incumbent George A. Wilson, a kindly, well-intentioned man, whom Gross criticized as not having done all he promised two years earlier. Gross’s voice was very familiar to Iowans, especially in the Hawkeye State’s rural counties. H. R. Gross disdained all the traditional means of campaigning and refused all invitations to attend events and shake hands. A good speech maker, Gross spurned making platform speeches and confined his talks to the radio. Gross came within 15,000 votes of upsetting Governor Wilson in the Republican primary.

For a brief time, Gross moved his family out of state, but he eventually returned home to Iowa. In 1948, Gross launched a campaign for Congress against another incumbent, John W. Gwynne, a Republican who had been first elected in 1934. Once again, H. R. Gross challenged the Republican organization, which backed Congressman Gwynne. The result surprised most everyone but H. R. Gross, who carried nine of the fifteen counties comprising Iowa’s Third Congressional District.

1948 was supposed to be a banner year for Republicans, who had swept the 1946 midterm elections to win both houses of Congress for the first time since 1928. Virtually every political prognosticator in the country believed the GOP presidential nominee, New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, would beat Harry Truman in the general election. Those same political pundits ignored the ominous signs that were readily apparent throughout the fall campaign, not the least of which was the number of Republican senators in danger of losing, which included Senator George A. Wilson of Iowa. Wilson was facing perhaps the most popular Democrat in Iowa at the time, Guy Gillette, a former U.S. senator. Both Gillette and Harry Truman carried Iowa that year, while H. R. Gross won a resounding victory at the polls, winning more than 58% of the vote in the Third Congressional District and carrying all fifteen counties.

Congressman H. R. Gross proved to be popular enough to weather even the fiercest political headwinds, which ended the careers of many other Republicans in the House. While his percentage dipped in 1958, when the country was in the midst of a serious recession, H. R. Gross still won decisively. The closest political contest of his long career occurred in 1964 when Lyndon Johnson crushed Barry Goldwater in the general election. Five out of six of the Republicans in Iowa’s House delegation were defeated that year; only H. R. Gross survived, who won by 419 votes. Two years later, Gross won reelection by more than 62% of the vote. 53 Republican congressmen had signed a letter urging the nomination of Senator Barry Goldwater as the GOP presidential nominee, and 23 of them were defeated in the 1964 Johnson landslide.

Irrespective of his majority, Congressman H. R. Gross never changed. Personally frugal, Gross continued to take stands that frequently puzzled others. When Congress decided to move many federal holidays to the nearest Monday, Gross opposed it, pointing out that doing so would deprive retail workers of the holiday, as businesses would remain open. Gross introduced a bill requiring a balanced budget during each of his 13 terms in the House of Representatives.

When the House of Representatives opened its first session in 1960, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn had “passed the word” that no significant business would occur during that week. As a result, many congressmen did not return to Washington, D.C., preferring to remain in their respective districts. Nobody would likely have thought much about it had not Congressman H. R. Gross called attention to the fact that much of official Washington was missing. Gross demanded a quorum call the first morning the House was back in session. There was no quorum to be had, and TIME reported Congressman Gross “kept the quorumless House in legislative limbo.”

Congressman H. R. Gross was generally a foe of the United States sending taxpayer dollars overseas in the form of foreign aid. During an uprising of some House Republicans in 1957, the Eisenhower Administration’s $3.8 billion foreign aid bill encountered some difficulties despite a special presidential plea. “I took my last marching orders in 1916-19,” Congressman Gross snapped, referring to his military service during the First World War. Gross was one of those voting to pare down the request from $3.8 billion to $3.1 billion, although he never voted for the bill to pass the House.

Gross proved to be a wily opponent, and when President Lyndon Johnson was pushing a $2.7 billion foreign aid bill through the House of Representatives, the Iowa congressman came within five votes of sending the entire bill back to a conference committee with an added amendment to end aid to Poland as long as that country traded with North Vietnam.

“Is the obligation of the United States to wet-nurse the rest of the world?” H. R. Gross wondered.

As the 1960 presidential election approached, Gross joined four of his GOP colleagues from Iowa in trooping to the office of Vice President Richard Nixon, who was the Republican presidential nominee that year. The Iowans were unhappy with the farm policies of Eisenhower’s Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson, and wanted to hear from Nixon what his own farm policy would be.

When the House voted in 1959 to create a new three-man federal commission to assist the coal industry, which was sickly, Congressman H. R. Gross complained, “No matter how thick or thin you slice it, this creates a new agency when we already are surfeited with them.”

Congressman H. R. Gross defied the conventional wisdom of his own party once again when he was selected to welcome Governor Ronald Reagan of California to a fundraising dinner in Iowa of some 10,000 people. Gross was a backer of Reagan, who was making a bid for the 1968 GOP presidential nomination; in fact, Reagan won more popular votes that year than Richard Nixon, who was the eventual presidential nominee. Gross was a national leader in Reagan’s insurgent campaign to topple President Gerald Ford for the GOP nomination in 1976.

Gross announced he would not run again in 1974. Gross chose not to go home to Iowa to live and remained in Washington, D.C., for the remainder of his life. The former congressman suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and died in a Washington veterans hospital at age 88 in 1987. The Cedar Rapids Gazette published an editorial remembering the longtime congressman and his career. The editorial quoted Dave Nagel, a Democratic congressman from Iowa, who said, “One has to admire the high integrity and principles H. R. Gross possessed in his career. While you may not have always agreed with him, you always knew where he stood.” The Gazette editorial stated it was no wonder the people of Iowa’s Third Congressional District kept H. R. Gross in Congress “for as long as he consented to stay.” © 2025 Ray Hill