The Gentleman From West Virginia

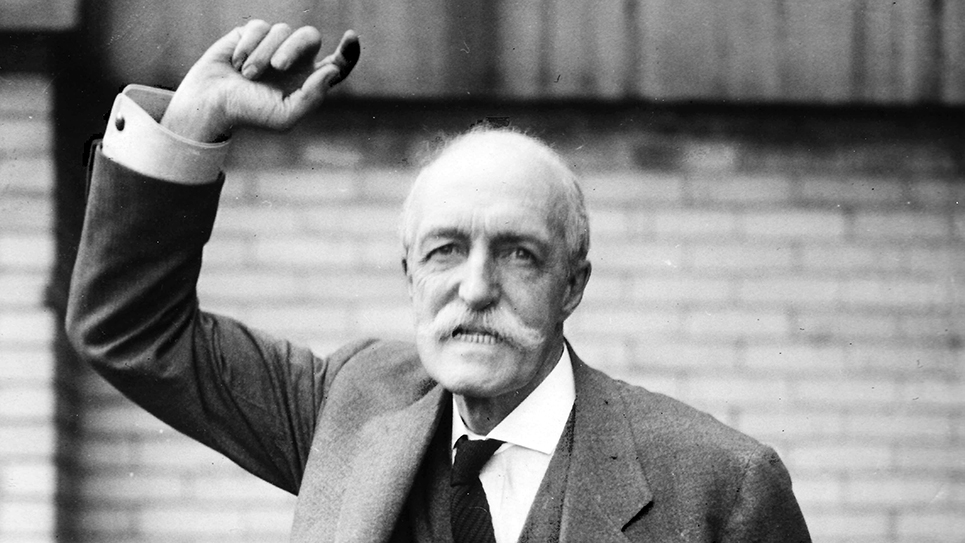

Cleveland Bailey

By Ray Hill

Cleveland Monroe Bailey looked more like movie director Tim Burton’s idea of a mortician than a congressman. Bald, jug-eared and slightly stooped, Bailey served a total of fourteen years in the U.S. House of Representatives from West Virginia. Like most any other successful Democrat holding public office in West Virginia, Cleve Bailey “preached the gospel pretty much according to John L. Lewis.” Lewis was the head of the powerful United Mine Workers and a significant political force in the Mountain State.

As we all know, looks can be deceiving, and while Cleveland Bailey looked mild and meek, he had a temper when riled. Bailey engaged in an altercation with Adam Clayton Powell, the congressman from Harlem, as the House Education and Labor Committee was meeting in closed session. Powell was attempting to amend a $1.6 billion school-construction bill in 1955. What Congressman Powell proposed was an amendment so that those school districts that practiced segregation would not be eligible for federal funds. Bailey was no arch segregationist; quite the contrary, the West Virginian had supported several of Powell’s civil rights measures in the past, but he worried the Powell amendment would kill the entire bill should it be attached to the funding measure. According to those who were present at the meeting, Cleveland Baily turned to Powell and snapped that if the committee adopted his amendment, it would be a mortal wound to the legislation. Bailey added that Powell knew that much himself.

“You are a liar,” Powell retorted.

As reported by the most widely read news magazine in the world, TIME, the 46-year-old, 6’4, 190-pound Powell never saw it coming. At least half a foot shorter, 69 at the time, and perhaps weighing 147 pounds, the enraged Cleve Bailey threw a punch that landed on Adam Clayton Powell’s cheekbone. The blow surprised Powell, who toppled from his chair backward. Bailey had reached down, grabbed his fellow congressman by the collar and was drawing back his arm to strike again when other congressmen pulled him off.

Powell’s amendment was defeated in committee, and the two congressmen shook hands and pretended the episode had never occurred. When asked about the tussle by newsmen, Powell deflected, saying, “Cleve Bailey and I smoke cigars together.” Bailey, too, denied it. “The whole thing never happened,” Bailey insisted. In the next breath, Bailey “showed reporters a half-inch cut on his right wrist, his only wound in the fight.”

Cleve Bailey began his career as an educator and was a high school principal in his home city of Clarksburg for several years before becoming superintendent of schools. Bailey’s first venture into politics was a short stint as a member of the Clarksburg City Council, and he worked for a decade as the editor of the Clarksburg Exponent. When the Democrats won control of the state government in the 1932 election, Cleveland Bailey was one of the deserving Democrats brought to the state capital of Charleston to work as an assistant to the state auditor. In 1941, Bailey became West Virginia’s budget director. Cleve Bailey still occupied that post when he launched his first bid for Congress against Republican incumbent Edward G. Rohrbough, who had served as head of the Glenville State Teachers’ College for 34 years.

With President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the head of the ticket, Democrats reversed the success Republicans had enjoyed in West Virginia during the 1942 election. Cleve Bailey narrowly beat Congressman Rohrbough by just over 5,000 votes. The two fought a bitter rematch in 1946, which was a good year for the GOP. Each candidate carried five of the district’s ten counties. Rohrbough was returned to Congress, beating Bailey by 2,500 votes.

The 1948 election was widely believed to be a cakewalk for the Republican Party after it won both houses of Congress in 1946. Thomas E. Dewey, governor of New York and the GOP presidential nominee, was leading Harry Truman in the polls and campaigned as if he were an incumbent. Dewey lent little support to Republican U.S. Senator Chapman Revercomb, who was seeking reelection. Ironically, Revercomb ran well ahead of Dewey in the Mountain State.

Organized labor was adamantly against Revercomb and the rest of the GOP ticket, which included four congressmen, all of whom had supported the Taft-Hartley Bill. Cleveland Bailey, encouraged by the closeness of his losing race in 1946, was the Democratic nominee once again in 1948. The former congressman ran a determined campaign against his predecessor and successor, intent upon reclaiming his seat in the House. The political pendulum swung back in a big way, and the Republican ticket in West Virginia took a beating at the polls. Bailey defeated Congressman Rohrbough by nearly 17,000 votes.

Congressman Bailey faced a formidable opponent once again in the 1950 election in the person of Rush D. Holt, once the wunderkind of West Virginia politics. Holt had been elected to the United States Senate in 1934 and had to wait six months before reaching the constitutionally required age of 30 to take his seat. Holt had been elected as a Democrat and was soon feuding with his senior colleague, Matthew Neely, who was the head of the federal faction in West Virginia. Rush Holt proved to be an irritant to the Roosevelt Administration and was one of the staunchest noninterventionists in the United States Senate. Holt lost the Democratic primary in 1940 to a candidate sponsored by Neely and returned to a seat in West Virginia’s House of Delegates. In 1950, Holt switched parties and became a Republican. Old-line Republicans were none too happy about Holt’s party change, and the former senator encountered strong opposition to his candidacy for Congress inside the GOP primary. Holt won the nomination easily, carrying 10 out of the 11 counties comprising the Third Congressional District. Holt’s party switch enraged many West Virginia Democrats, and they fought his candidacy with an intense fury. As Rush Holt campaigned, he exhibited a confidence in the outcome of the election that unnerved some Democrats and caused others to be highly annoyed. Senator Neely and Governor Okey Patteson came to the district to campaign on behalf of Bailey. It was also an indication of state Democrats’ concern over the possibility of Rush Holt returning to Capitol Hill.

“Cleve is going to need all the help he can get, and it will take more than Matt Neely can give him,” Holt told one reporter.

Congressman Bailey’s campaign revived Holt’s record as an isolationist while serving in the U.S. Senate. The Bailey campaign bought large ads in weekly and daily newspapers urging West Virginians to “Support a Patriotic American” by reelecting Bailey.

Rush Holt carried the more rural counties of the Third District, but he was overcome by the majorities Bailey piled up in the more urban areas. Still, the former senator won 45% of the vote. After defeating Rush Holt, Cleveland Bailey had tightened his hold on his seat in Congress and was elected by increasing majorities throughout the decade of the 1950s. Bailey had won the 1960 election with almost 60% of the vote over his GOP opponent.

West Virginia’s loss of population necessitated the loss of one congressional district and

Democrats contrived to rid themselves of the lone Republican in the congressional delegation, Arch Moore (father of Senator Shelley Moore Capito), who had first been elected in 1956. Moore, who had been grievously wounded during the Second World War, was a gifted campaigner and had proved to be highly popular inside his congressional district, easily winning reelection every two years despite Republicans being a distinct minority. When they could not achieve at the ballot box, West Virginia Democrats decided to reshuffle and stack the deck through redistricting. The West Virginia legislature combined the districts of Arch Moore and Cleveland Bailey, believing Bailey’s seniority would help him win the general election without too much trouble. The legislature had seen to it that the district favored the Democrats through a 51,000-voter registration advantage, which they felt confident would buoy Bailey’s chances.

To bolster Bailey, the Democrats sent former President Harry Truman to campaign for the congressman. A widely covered event was the visit by President John F. Kennedy, who came to stump for Congressman Bailey. Any time a president of the United States visits a particular city, it is a spectacle as the chief executive travels with all the pomp and circumstance of his office. President Kennedy traveled to Wheeling, West Virginia, specifically to support Congressman Cleveland Bailey. Both of West Virginia’s United States senators, Jennings Randolph and Robert Byrd, were on hand, as was Governor Wally Barron and the four Democrats who represented the Mountain State in the U.S. House of Representatives. West Virginia was the place where Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign really caught fire. For those who believed a Catholic could not be elected nationally, West Virginia was an important proving ground, as the Mountain State was overwhelmingly Protestant. When John F. Kennedy handily beat Senator Hubert Humphrey, who had the backing of Robert Byrd, it demonstrated his personal appeal was greater than the prejudice against his religion. There was no question about John F. Kennedy’s personal popularity with the majority of West Virginians.

Kennedy made a fighting political speech, but he made an embarrassing verbal error when he called out the West Virginia congressmen, including Arch Moore. The president quickly corrected himself as the audience laughed. Arch Moore enjoyed telling the story of Kennedy’s mistake for the rest of his long life.

Four members of President Kennedy’s Cabinet came to West Virginia to campaign for Bailey, as did Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., son and namesake of the late president. Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives John McCormack and Majority Leader Carl Albert both came to West Virginia to campaign for Cleve Bailey. Organized labor flooded the district with messages stating Bailey “MUST be reelected and returned to the 88th Congress. Labor needs all the friends it can muster. Cleve Bailey is one of the best.”

Unfortunately, for Bailey, the campaign visits seemed to cause some West Virginians to complain about outside interference in the election. Yet Arch Moore was a resourceful and excellent campaigner and had entrenched himself during his six years in Congress. Moore was 39 while Cleveland Bailey was 76 years old. Voters in West Virginia’s First Congressional District chose the future and closed the books on the past, giving Arch Moore a surprisingly large victory. Congressman Moore won nearly 60% of the ballots cast.

Moore had run well across the district, even in territory that was new to him. The Republican congressman made a strong showing in Bailey’s home county and demonstrated his ability to attract votes from voters who considered themselves Democrats.

Bailey’s loss was all the more astonishing considering he had the full backing of the Kennedy Administration, as well as that of Governor Barron on the state level as well as organized labor. Moore’s defeat of the veteran Congressman Bailey drew national attention; the United Press International ranked Moore’s win as one of the top news stories for West Virginia during 1962.

Nobody was more surprised by the election results than Cleve Bailey. The elderly congressman checked into Bethesda Naval Hospital for a “rest,” according to his Capitol Hill office. That was Bailey’s second visit to the hospital following the election. Bailey had stayed almost a week in the hospital just after his defeat.

Under Secretary of Commerce Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr. spied the former congressman in the audience at a meeting of the Appalachian Regional Conference. Roosevelt approached the 77-year-old ex-congressman and grabbed his hand and shook it warmly. “We miss you in Washington,” Roosevelt told a beaming Bailey. Cleve Bailey readily admitted, “My heart still is interested in West Virginia.”

The former congressman was suffering from serious kidney disease and had entered a hospital in Charleston, where he had lived for years. Bailey died July 13, 1965, just days before his 79th birthday.

© 2025 Ray Hill