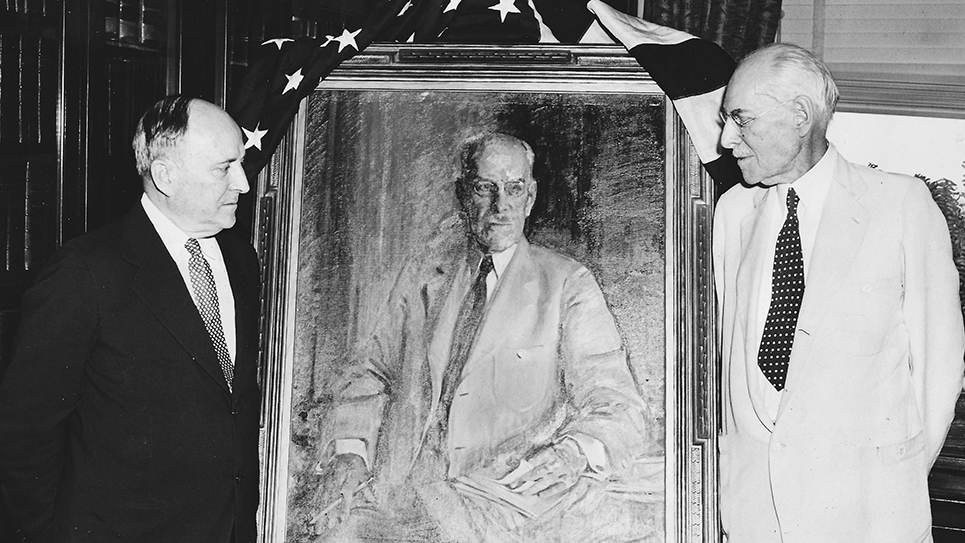

The Gentleman From Colorado

Edward T. Taylor

Edward Thomas Taylor served 32 years in the U.S. House of Representatives for Colorado. Taylor didn’t get to Congress until he was 50 years old and stayed there until his death at age 83. By the time Congressman Ed Taylor died, he was one of the leading figures in the House, serving as chairman of the House Appropriations Committee. That post was, in Taylor’s opinion, “the second hardest job in Congress.” “Speaker of the House is first,” Taylor told a reporter. “I believe the grind hastened the deaths of the six men who were chairmen immediately before me.”

Twenty-two times Edward T. Taylor ran for public office in general elections and never once was defeated. Tall, wiry and balding as he aged, Taylor favored gold-rimmed glasses and wore a moustache. Taylor had been a cowboy in Kansas and attended law school at the University of Michigan. He claimed, not without reason, in his biography in the “Congressional Directory,” that he had written “more state laws and constitutional amendments and federal laws combined than anyone else.” Taylor was called the “Father of Reclamation” by many for his conservation efforts. Friendly, kind and unfailingly courteous, it was said that Ed Taylor served in the House of Representatives for more than 30 years without making a single enemy. For the first six years of his congressional career, Edward T. Taylor was elected at-large by all the people of Colorado.

Perhaps the most famous piece of legislation authored by Congressman Edward T. Taylor was the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. Taylor proposed that grazing be allowed on 80 million acres of land owned by the United States government. The land would be subdivided into grazing districts, which would be administered by the Department of the Interior. Today, there are at least 162 million acres with grazing allotments. The Taylor Grazing Act provided for landowners surrounding the federal lands to be able to request and receive permits to grant passage across lands and grazing privileges, and to build fences and other necessary improvements. The legislation also outlined the exceptions, which included Alaska (a territory when the bill was first passed), national forests and national monuments. Ranchers paid fees for the use of the lands, which went to pay for conservation and improvement projects, as well as turning over some of the revenue to the various state governments. There was terrific opposition to the Taylor Grazing Act, and opponents called for the individual states to use and dispose of the range as they wished.

Taylor never hesitated to use his growing influence on behalf of Colorado and the West and was an integral factor in twice saving the Boulder Dam from congressional defeat. The Colorado congressman was one of the major factors in the success of the Colorado River Compact. That helped in making the Boulder Dam possible, and Taylor supported the development of Muscle Shoals, a matter of considerable interest to the people of Tennessee and their congressional delegation. Congressman Taylor was a strong advocate of hydroelectric power. Taylor also fervently believed in the multiple use of land. The Colorado congressman sponsored the Taylor-Mondell Act with Frank Mondell of Wyoming. That particular bill opened federal coal lands for settlement while simultaneously protecting the fuel reserves.

Colorado’s Fourth Congressional District during Taylor’s service in the decade of the 1930s was imposing. Taylor’s home was in Garfield County, which was 75 miles wide and 120 miles long. It took a train ten hours to cross Colorado’s vast Fourth District. One reporter noted Colorado’s Fourth District included “some of the most celebrated gold towns of the mining era,” as well as “immense forest reservations; the fountainheads of eight large rivers, and 40 mountain peaks each of which is more than 14,000 feet in height.” Ed Taylor was praised by many journalists who believed no man had done more “to preserve the natural resources of” his district and the West.

Ed Taylor was evidently unassailable inside his district and especially inside the Democratic Party, as he never had an opponent for the nomination of his political party. Taylor liked to say he quite nearly settled upon being a teacher rather than a legislator.

“I got off a Kansas cow pony and went to Leavenworth, Kansas high school and then got a job teaching at Leadville, Colorado,” Taylor remembered. “I was paid $137.50 a month and saved $100. At the end of eight months, they wanted me to be school superintendent.” Taylor turned down the offer, using his $800 in savings to finance his law school education.

At the age of 26, law degree in hand, Edward T. Taylor returned to Leadville, where he began his public service career. Upon his return, Taylor recalled folks had not forgotten him and had “the county superintendency of schools virtually thrust upon me.” After being elected district attorney, Taylor decided, “Leadville’s two-mile-high altitude was too much for me.” Taylor moved to Glenwood Springs, where he lived for the rest of his long life.

It was in Glenwood Springs that Taylor built a home in 1904, which still stands there today. The exterior was painted white, and the Colonial Revival front porch was supported by thick columns that gave the home a vaguely Southern appearance. The Taylor House was built in the Foursquare style of the day. Originally, Taylor had budgeted $8,000 (which had the buying power of more than $277,000 today) for the construction of the house. Eventually, Taylor spent more than twice that building the house. The Taylor House had more than 7,000 square feet with three full floors and a basement. There were some lavish touches, like the entrance hall being paneled in Philippine mahogany.

Western senators and congressmen were expected to advocate for a number of things peculiar to their region of the country, not the least of which was water rights. Cattle, sheep, sugar beets, silver and other interests occupied much of the time of those who wished to remain in Congress while serving a western state. Taylor served in the Colorado State Senate for two terms before winning election to Congress in 1908 from the Centennial State’s Fourth Congressional District.

It was Congressman Ed Taylor who authored the legislation that changed the name of the Grand River to the Colorado River. Taylor was well-positioned to serve the interests of Colorado with his committee assignments in the House, serving on and chairing the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee and the powerful Appropriations Committee. With the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, Taylor used his perch on the Appropriations Committee to lavish projects and federal dollars upon the Fourth District and Colorado at a time when jobs and money were scarce. Taylor secured appropriations over $10 million annually for reservoirs, CCC camps, roads, and a host of New Deal alphabet agencies in his home state.

In 1935, only two men were left serving in the House of Representatives who had arrived in 1909: Taylor and Joseph W. Byrns of Tennessee, who represented the “Hermitage District” of Nashville. Byrns had just become the Speaker of the House while Taylor was the Acting Majority Leader in the absence of Alabama’s William Bankhead, who was quite ill. Only Adolph Sabath of Illinois had served longer and he by just two years. Ordinarily, Taylor was the ranking member of the House Appropriations Committee and presided over the Democratic Caucus of the House. Taylor’s chairmanship of the House Appropriations Committee’s subcommittee on the Interior Department gave him enormous influence on matters of importance to Colorado and the western United States.

James “Buck” Buchanan of Texas died on February 22, 1937. The death of Congressman Buchanan elevated Edward T. Taylor to the chairmanship of the House Appropriations Committee. Buchanan’s death also began the elective political career of a young congressional aide named Lyndon Johnson.

Taylor collected gavels, and his more than 50 gavels weighed more than 200 pounds. The congressman was the recipient of a specially-made gavel sent to him by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes.

As Taylor assumed the chairmanship of the House Appropriations Committee, President Roosevelt was once again talking about balancing the budget. The Colorado congressman remained skeptical. Taylor celebrated his 79th birthday shortly after assuming his post as chair of the Appropriations Committee. “We’ll have a birthday dinner together,” Mrs. Taylor told a newsman, “but there won’t be any guests nor even callers.” The aging congressman had only recently recovered from a month-long bronchial illness.

Edward T. Taylor had been in Washington a very long time and as he got older and his health more fragile, his visits back home became less frequent. Reelected easily in 1940, the congressman wanted to come back to Colorado with Mrs. Taylor for a vacation.

Friends had worried about the elderly congressman coming home for a visit. Walter Walker, publisher of a daily newspaper and a former U.S. senator, had written the congressman, begging him not to come home due to Colorado’s high altitude. Other friends tried to get the congressman to change his mind, but Taylor insisted he was coming home after having been absent from the state for the last three years. Mrs. Taylor, the same age as her husband, had been ill for some time, and the congressman thought she was much better and would enjoy the trip to Colorado. Both Congressman and Mrs. Taylor were excited about their homecoming and were in excellent spirits. Worried, Congressman Lawrence Lewis, who represented Denver in the House of Representatives and lived in the same Washington, D.C. hotel as the Taylors, made arrangements to travel on the same train back home. Lewis saw the Taylors off to their hotel in Denver, and the couple remained cheerful while the congressmen greeted a number of old friends. Friends were finally able to convince Congressman Taylor to reduce some of his schedule, which they feared was too strenuous for him. The following morning, a Tuesday, Congressman Edward T. Taylor suffered a severe heart attack in his hotel suite. While waiting for a physician, Taylor’s “recovery” was considered “remarkable” by some of those present. The doctor wisely insisted that Taylor be taken to a hospital immediately, which brought a protest from the congressman. Taylor eventually gave in, but also insisted upon dressing himself for the trip and getting to the car. The lawmaker was accompanied by Mrs. Taylor, Congressman Lewis and former Governor Teller Ammons.

Ed Taylor was quickly placed under an oxygen tent, a standard practice of the time. The next day, a Tuesday, Taylor seemed to be improving, but he suffered another, slight heart attack that evening. On Wednesday, Congressman Edward T. Taylor was active, seeing friends and visitors, and making plans for his visit. Mrs. Taylor and a nurse were sitting with him when the congressman died suddenly at 8:05 p.m. At the time of his death, Edward T. Taylor was the oldest man serving in the House of Representatives.

Taylor had never shown the slightest inclination to retire; quite the contrary, the congressman had stated several times he wished to die while “still in harness.” Granted that wish, Congressman Edward T. Taylor authored more than 100 federal laws for the people of Colorado and the United States.

The funeral of Congressman Ed Taylor was held at the American Legion Hall, and the floral tributes squeezed those attending the services. Flowers came from the White House and President Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, as well as from modest homes of those who appreciated the congressman’s service. The Roosevelts had sent dark red roses with a sprig of wheat. Tributes from the House, the U.S. Senate, and the various departments, agencies and armed services were everywhere.

© 2025 Ray Hill